South Central: Social Distance and Social Justice

Theatres in Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana face budget shortfalls, existential questions, and a new sense of purpose.

Art by Monet Cogbill

Art by Monet Cogbill

It’s a paradoxically barren and fertile time to be writing and thinking about theatre in the U.S. Like so many other practices and industries, theatres have been hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic that at the moment is raging out of control across our nation. Performances have been canceled and workers laid off or furloughed, with very few folks anticipating a full return to the stage until early to mid-2021.

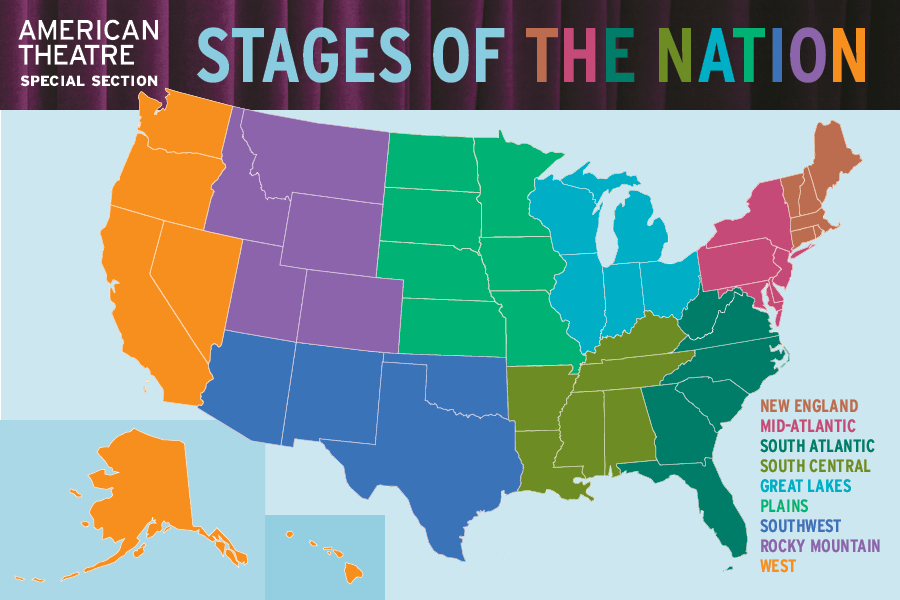

In the wake of this sudden hiatus, we commissioned a series of “check-ins” with a handful of theatres in each of the nine regions (as TCG defines them, key above) to see how they were faring and what they were planning (special thanks to Eric Grode and Syracuse’s Goldring Arts Journalism program for reporting, and to Jerald Raymond Pierce for the assignment editing). In the midst of this reporting, George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police, and the Black Lives Matter movement resurged at long last into the global consciousness. In the theatre world, this gave considerations of fundamental restructuring, already on the table, a fresh and pointed urgency.

And as we got closer to press, a group of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) theatre leaders and workers launched an anti-racist movement called “We See You, White American Theater” to call out the persistent racial inequities perpetrated and perpetuated by the nation’s dominant nonprofit and commercial theatres, and later the collective released an ambitious 29-page list of demands for the field that promises to set the terms of debate and reform for the coming years, as two pieces by Jerald Raymond Pierce, and one Ciara Diane, lay out. Not in direct response to these demands but as a complement to them, Aeneas Sagar Hemphill posits a historical model for the shape some of those changes could take.

In short, there’s a lot to weigh and question about the way theatre has traditionally done business within a system built on capitalist and colonialist structures. And while theatres are on an enforced hiatus, we are here joining that nationwide weighing and questioning. I think that much of our current moment of gravity and consideration is reflected in the package of stories we’ve put together. But not all of it: Dismantling so-called white supremacy in our work and our lives is an ongoing project.

This should give us hope and purpose, however, rather than despair. As Baltimore Center Stage artistic director Stephanie Ybarra put it to me, “My approach to the demands document is, pick a place to start, then pick another place, and keep going. The thing I take heart in is that the work will never be done.” Which means we all have something to do.

—Rob Weinert-Kendt

Theatres in Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana face budget shortfalls, existential questions, and a new sense of purpose.

As the pandemic rages through Arizona, Texas, and Oklahoma, theatres adjust their models and make new commitments, while one New Mexico theatre goes under.

Theatres in California, Oregon, Nevada, and Washington know they can’t go back to normal, and increasingly they’re seeing they wouldn’t want to anyway.