We stand at a critical crossroads in American history—a crossroads where democracy, creative expression, artistic freedom, and the very artists and arts institutions that uphold these ideals face unprecedented threats. It is not lost on me and so many others that one of the first political acts by the current administration—23 days following the inauguration—was the takeover of the Kennedy Center, the national cultural center of the United States. Nobel Prize-winning writer Toni Morrison makes clear an urgent truth:

I want to remind us all that art is dangerous. I want to remind you of the history of artists who have been murdered, slaughtered, imprisoned, chopped up, refused entrance. The history of art, whether in music or writing or what have you, has always been bloody, because dictators and people in office, and people who want to control and deceive, know exactly who will disturb their plans. And those people are artists.

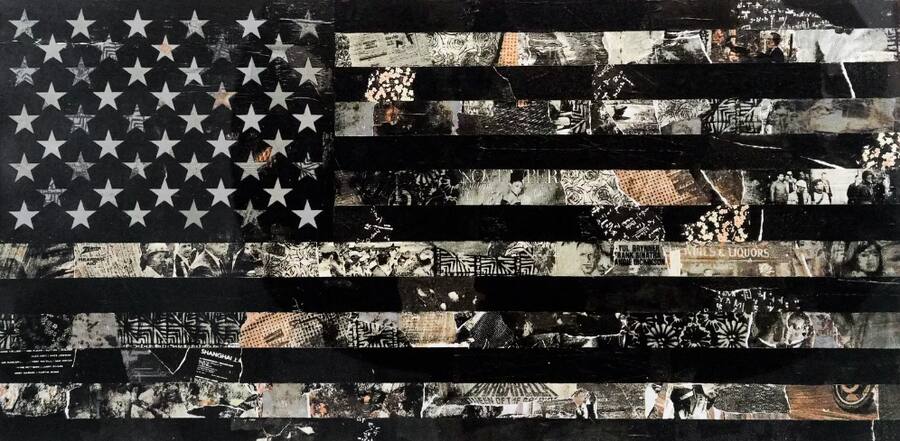

At the heart of these threats lies the potential to erode our very civilization—to degrade the cornerstone of America’s enduring experiment in democracy and pluralism. This cornerstone is rooted in the moral arc of the universe, made more dynamic by former Attorney General Eric Holder when he shared, “The arc of the moral universe bends towards justice—but only when we put our hands on that arc and pull it.” The erosion of civilization would halt that collective pull, silencing the voices and perspectives that embody humanity, decency, beauty, truth, and justice. This is no abstract concern; it is a crisis that demands immediate attention and action, as it risks leaving permanent tears in the already fragile fabric of America’s rich and diverse tapestry.

In a fabled lecture, anthropologist Margaret Mead once posed the question, “What is the earliest sign of civilization?” Students suggested answers like a clay pot, tools, or weapons. Mead responded, “The first sign of civilization is a healed femur.” The femur, the longest bone in the body, connects the hip to the knee. In societies without modern medicine, healing a fractured femur requires about six weeks of rest. A healed femur shows that someone cared for the injured person, providing support and protection until the injury healed. Mead explained that in societies where the rule of law is survival of the fittest, no healed femurs are found.

I am a first-generation Black American woman with Indo-Guyanese ancestry and Southern roots, raised in a lower socioeconomic environment in Southeast Washington, D.C., and Newport News, Virginia. It became clear to me early on that art was not readily accessible to all people. In those formative years, I began to shape what has since evolved into a core conviction: The arts are a fundamental right for all people. As an arts leader, a mother of a daughter, and an artist, I strive to make sense of and bring clarity to an increasingly complex world through the transformative power of creative expression. My work is a continuous search for truth.

This written reflection is rooted in the microcosm of these intersecting identities, understanding that U.S. arts institutions—more than 100,000 strong across the nation—are the cultural anchors that shape the collective consciousness of a country. As Christopher Robichaud, senior lecturer in Ethics and Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School of Government, shared: “This would be the time for the arts, broadly understood, to step in. The arts can change hearts and minds.”

The future of arts organizations, especially those serving the most vulnerable segments of society, hangs in the balance. This fragility is deeply rooted in generations of historical inequities, which have shaped the arts sector, determining whose stories are told, whose voices are heard, and which artists and communities are given the resources to flourish. As August Wilson poignantly declared in his 1996 speech The Ground on Which I Stand, “Black theatre in America is alive, it is vibrant, it is vital…it just isn’t funded.” These words resonate as powerfully today as they did decades ago, not only for Black theatres, but for all arts institutions whose unyielding quest for visibility, recognition, resources, and opportunity stands at a pivotal crossroads.

The stark reality of these inequities is laid bare in the data. The 2017 Helicon Collaborative report Not Just Money: Equity Issues in Cultural Philanthropy reveals that 58 percent of cultural philanthropic support for arts organizations flows to just 2 percent of the largest institutions—those predominantly centered on Western and European art forms. Meanwhile, 98 percent of arts organizations, and the communities they serve, are left with only 42 percent of that funding. This study also reports that a mere 4 percent of all foundation arts funding is allocated to groups whose primary mission is to serve communities of color—i.e., the arts institutions on the frontlines of addressing long-standing community disinvestment and vulnerabilities.

It is meaningful to look across sectors and challenge the disinvestments, even in our own communities. Woodie King Jr., in his 1981 book Black Theatre: Present Condition, explains that “wealthy Black Americans, I am sorry to say, do not invest” in Black institutions or projects. “Wealthy Black Americans invest in AT&T or Twentieth Century Fox.” A survey by the DeVos Institute found that the median budget of the nation’s 20 largest arts organizations of color is 90 percent smaller than their mainstream counterparts, with many operating on the brink of financial collapse. It goes without saying that vulnerable institutions are seeing long-standing disinvestments in almost all of the diverse revenue streams that are necessary for greater sustainability, community impact, and service to the common good.

“If arts and culture are primary ways that we empathize with, understand, and communicate with other people—including people different than ourselves—then enabling a broad spectrum of cultural voices is fundamental to creating a sense of the commonwealth and overcoming the pronounced socio-political divides we face today,” wrote Holly Sidford and Alexis Frasz in Not Just Money.

The defense and lasting strength of our most fragile institutions and communities—that is the true frontier ahead of us. That is the building of a civilization.

The ravaging effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and the reckoning with racial injustice continue to reverberate throughout the arts sector, with most institutions still reeling. This moment demands visionary and decisive action, and it demands a reliance on the freedom of spontaneous creativity with the certainty of intentional conviction—a.k.a. jazz improvisation—to secure the survival of our arts ecosystem, even without the certainty of a notated score or blueprint for what comes next. As Miles Davis once said, “It’s not the note you play that’s the wrong note—it’s the note you play afterwards that makes it right or wrong.” A spontaneous creativity is especially critical for the institutions most at risk.

By no means does my reflection here seek to divide or to diminish the struggles unfolding across the broader arts and culture sector. I believe that we must work together and create solutions as a wider collective. But this reflection is aimed at prioritizing resources for those communities and institutions historically overlooked and most in need during this ongoing crisis—institutions and communities directly in the line of fire. These institutions have focused on immigrants, people of color, the LGBTQ+ community, the disability community, women and girls, and the economically disadvantaged. By increasing support in these areas, we can realize a ripple effect that ensures “all boats rise” across the sector, as we fight for the very soul of our democracy, and indeed, the soul of our civilization.

I am inspired by the work of PolicyLink founder Angela Glover Blackwell, whose championing of the “curb cut effect” provides a powerful lens for this advocacy. The curb cut on sidewalks was originally designed to assist people with disabilities. But this simple, yet profound intervention has proven to benefit everyone from parents with strollers to bikers, travelers, and workers. The principle behind the curb cut effect is that policies aimed at uplifting the most vulnerable often lead to societal benefits that ripple outward, strengthening the collective whole.

“There’s an ingrained societal suspicion that intentionally supporting one group hurts another,” Glover Blackwell wrote in “The Curb-Cut Effect” for the Stanford Social Innovation Review in 2017. “That equity is a zero sum game. In fact, when the nation targets support where it is needed most—when we create the circumstances that allow those who have been left behind to participate and contribute fully—everyone wins. The corollary is also true: When we ignore the challenges faced by the most vulnerable among us, those challenges, magnified many times over, become a drag on economic growth, prosperity, and national well-being.”

Leaders who serve historically disadvantaged cultural institutions and communities are not lacking in vision, skill, imagination, or the cultural nuances and sensibilities that can only come from within our communities. What is required now are sustained investments and an unshakable belief in our capacity to lead, to be critical changemakers and thought leaders, and to dynamically contribute to a vibrant, flourishing arts ecosystem that anchors a civilization at risk.

Technology is critical to our future, but it is not the next frontier. The construction of larger and more advanced buildings plays a vital role in the growth and expansion of our ecosystem, but they are not the next frontier. The defense and lasting strength of our most fragile institutions and communities—that is the true frontier ahead of us. That is the building of a civilization. A. Philip Randolph, leader of the historic 1963 March on Washington, reminded us that “a community is democratic only when the humblest and weakest person can enjoy the highest civil, economic, and social rights that the biggest and most powerful possess.”

Without well-orchestrated and highly coordinated interventions and partnerships among the philanthropic, corporate, community, and arts and culture sectors, these long-standing fragile institutions may shutter, recalling the time when federal funding cuts in the 1990s meant that 87 percent of Black theatre institutions at the time were unable to keep their doors open. Just in New York City, eight African American theatres closed in the 1990s, as Samuel A. Hay recorded in African American Theatre: An Historical and Critical Analysis (Cambridge University Press, 1994). Without the larger arts and culture sector protecting the very institutions that hold and embody the rich diverse narratives that are our great pluralistic and democratic experiment, the arts and culture sector could very well become part of the cultural monolith that we are trying to push back against—one that builds empires and not civilizations.

I understand that equity is not a monolithic or singular construct, but a complex and multifaceted intersectionality. It is woven through the threads of race, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, faith, and so much more. This nuanced, holistic understanding is the frontier we must embrace if we are to advance together. So many institutions across this vast and beautiful cultural sector have stood resolutely at the intersection of social justice and the arts, serving as guiding lights for marginalized voices to be heard and celebrated. Now, as we face this pivotal moment, we must stand poised to redefine the very role of arts institutions and reach a resounding radical consensus—to challenge the status quo, to reimagine our purpose, and to set about “imagining a world,” in the words of Audre Lorde, “in which we can all flourish.” With the need to exercise unprecedented courage, conviction, and an indefatigable commitment to building a civilization that will live past our time—as one plants trees under whose shade they may never sit—we can rise to defend this right, stand against the forces that seek to dismantle it, and shape a future where healed femurs abound, standing as a living testament to our shared humanity and the unbreakable strength of a collective will to heal our fragile and fractured democracy.

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Alice Walker admonished: “The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don’t have any.” I would humbly recommend a few actions that can be taken now. I am confident there are many more.

- A National Cross-Sector Arts Task Force: This task force would bring together national leaders from philanthropies, corporations, communities, and the arts and culture sector with a focus on a strategic, multi-year plan to invest in arts institutions that are specifically in the line of fire at this time: immigrants, people of color, the LGBTQ+ community (particularly trans people), the disability community, women and girls, and the economically disadvantaged.

- Community Standing with Community: Community leaders, community members, and businesses can seek out vulnerable institutions and invest in them: buy tickets, donate (giving at every level is meaningful), and create sponsorships and partnerships to build resiliency and greater connections among the community. Volunteer! If there is a skill or pro bono service that can be provided to move an institution forward, provide it. Make Some Noise! For these vulnerable institutions who may be in danger of closing their doors in silence, don’t let it happen. Share their website and upcoming events on social media to keep them alive and well. Use your influence. Share with your followers.

We have the power to reimagine the world, but only as a collective. In the midst of World War II, Pulitzer-winning writer Katherine Anne Porter penned a sentiment in 1940 that resonates with the struggles we now face—words that provide hope, encourage us to take the long view, and propel us forward…together:

In the face of such shape and weight of present misfortune, the voice of the individual artist may seem perhaps of no more consequence than the whirring of a cricket in the grass, but the arts do live continuously, and they live literally by faith; their names and their shapes and their uses and their basic meanings survive unchanged in all that matters through times of interruption, diminishment, neglect; they outlive governments and creeds and the societies, even the very civilization that produced them. They cannot be destroyed altogether because they represent the substance of faith and the only reality. They are what we find again when the ruins are cleared away.

Dr. Indira Etwaroo is a producer, director, scholar, and arts and culture executive. She is artistic director and CEO of Harlem Stage.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.

Related

New Performing Arts Complex Opens in New Brunswick

The New Brunswick Performing Arts Center will present works from New Jersey arts organizations.

In "Mid Atlantic"

To Own or to Rent? That Is the Question

Each path has its pros and cons, its complications and its trade-offs, as these case studies show.

In "Paywall"

Know a Theatre: Crossroads Theatre Company in New Brunswick, N.J.

The New Brunswick Performing Arts Center's resident company started in a former sewing factory and will move to a new state-of-the-art complex this fall.

In "Know a Theatre"