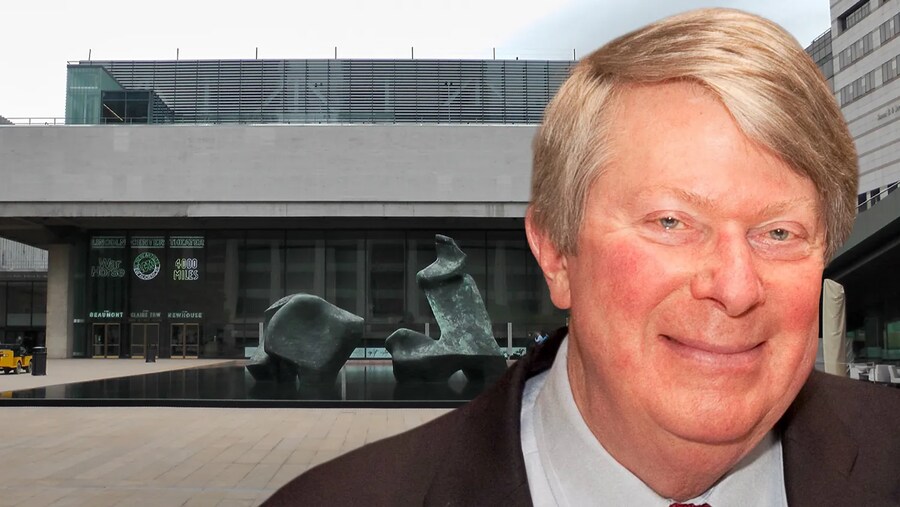

“I was in school with Aeschylus,” quipped director Jack O’Brien in a recent joint interview with André Bishop in the latter’s book-lined office at Lincoln Center Theater, the three-theatre powerhouse that Bishop is about to relinquish after 33 years as LCT’s artistic director (the last 10 with the title producing artistic director).

As much as he and Bishop may josh about their advanced ages—85 and 76, respectively—they have both remained vital creative forces in the American theatre for more than four decades. Both launched their careers proper in the 1980s: O’Brien as artistic director of San Diego’s Old Globe, a post he held from 1981 to 2007, and Bishop as artistic director of Playwrights Horizons in its 1980s heyday, when it served as the launching pad for the likes of Christopher Durang, Wendy Wasserstein, and William Finn, and as the first Off-Broadway berth for Stephen Sondheim when James Lapine brought him along to do Sunday in the Park With George. (A 3-D set model from Sunday adorns Bishop’s office to this day.)

They had already been friendly for some time, but their careers didn’t intertwine professionally until the beginning of Bishop’s tenure at Lincoln Center Theater in 1992, when O’Brien directed Two Shakespearean Actors (in fact the final production of Bishop’s LCT predecessor, Gregory Mosher). If O’Brien’s wildly diverse career as a freelance director can be summed up at all, it is that it bears out a kind of vivid, fearless versatility, taking him from all-stops-out Broadway musicals (Hairspray, The Full Monty, Carousel, Shucked) to meaty dramas (such LTC credits as The Coast of Utopia, The Nance, The Little Foxes, Henry IV), and all points in between.

Bishop’s long career as an artistic director, meanwhile, might best be defined by extraordinary taste, not only for writers, which he first developed as Playwrights Horizons’ literary manager, but also for directors and designers, a talent pool he dipped into at Playwrights and has filled and refilled several times over at the well-resourced LCT, which has two thrust stages, the Broadway-eligible Vivian Beaumount and its Off-Broadway mini-twin, the Mitzi Newhouse, as well as the 112-seat new-play incubator, the Claire Tow.

O’Brien has been among Bishop’s stable of go-to LCT directors, which over the decades has included the likes of Gerald Gutierrez, Dan Sullivan, Graciela Daniele, Bartlett Sher, and Lileana Blain-Cruz, among several others. Their valedictory project together is Ghosts, Henrik Ibsen’s thorny 1881 drama, in a frank new version by Mark O’Rowe that premiered in 2023 at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre and opens at LCT next Monday, March 10 (and has already announced an extension through April 26). It is, remarkably, the first by the Norwegian dramatist staged in LCT history (though the theatre’s predecessor at the Beaumont, the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center, did stage A Doll’s House and An Enemy of the People). And it features both a seasoned cast—Hamish Linklater and Lily Rabe, the real-life couple whom O’Brien memorably directed as Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado About Nohting for the Public Theater’s Shakespeare in the Park, and Billy Crudup, whose own career is intertwined with LCT and O’Brien—alongside newcomers Ella Beatty and Levon Hawke. Also remarkably, it’s being staged not in the sumptuous Beaumont, the usual place for classics and revivals, but in the intimacy of the 299-seat Newhouse.

In other words, Ghosts represents a bona fide artistic final statement, not a mere victory lap for the peripatetic director and the thoughtful producer. Following are excerpts from my lively conversation with them.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: You two have been working together since André’s first season at LCT. How did you two first meet?

JACK O’BRIEN: It’s a sweet story. As the Old Globe artistic director, I was on this NEA panel, which gives the money to various places. It was the summer, in the worst part of the Washington heat, and there was nothing going on. One Saturday afternoon I thought to myself, “They won’t miss me today.” In town at the National Theater was the touring company of something called Legends! with Carol Channing and Mary Martin—a famously awful show—and I thought, I gotta go see this. So I snuck out and I bought a ticket to the matinee. I got to my seat in the back of the theatre, and who was sitting next to me? André Bishop. We sort of fell into each other’s arms and we’ve never been apart since then.

How did Ghosts emerge as your final project together here?

ANDRÉ BISHOP: We were looking for a play to do. I said, “I’m ending my many years at Lincoln Center Theater, and Jack, I really, really, really, really, really, really want you to direct one of my last shows.” I might have even said, “I don’t even care what it is.” So we made lists of plays, and meanwhile, Jenna [Clark Embrey], our literary manager, had shown me this copy of of new translation by Mark O’Rowe of Ghosts that the Abbey Theatre had done a year ago, so it’s brand new—I think this is the second production. I read it and was very impressed with it, and then I gave it to you.

JACK: You did. I was sentimentally aware that this was our last duet, so I thought, are there people we feel should be in this moment? This is not just another show in the rep. You don’t want to just be random; you want to say, “There’s a reason for us to do this.” I’d had this wonderful experience with Lily and Hamish a few years back at Williamstown, and they also played Beatrice and Benedick for me in the Park. I’m always deeply concerned about the resonance of young actors who have an appetite for major drama. You need to use your body. You need to use your voice. You need to be more than sincere. We’re in a very, very low-ceilinged period right now of interesting, diverse work, but not necessarily work that is either spiritually connected or resonates in terms of the larger world. So I thought: We should go out with a bang, not a whimper.

Here’s the other thing: There is Ella Beatty and Levon Hawke, a generation below the generation I’ve been working with. So in terms of a fond goodbye, how lovely to be able to not only pay this attention to something that’s important to me, but to touch another tier of talent that we would love to infect with the joy and passion we feel for these works.

ANDRÉ: We had a very emotional first day of rehearsal—you know, when everyone gathers and introduces themselves and the producer makes a speech, the director makes a speech. There were many vibrations going on in the room, of old friendships, not just ours, but others—designers who had worked with Jack or me, or both of us together, for years; the sound designer I’ve known since Playwrights Horizons.

And the actors, these two generations: We had these two young ones, and then we had the older ones, including Billy Crudup, who made his professional debut here at the Beaumont years ago in Arcadia, when Daniel Swee, our casting director, found him at NYU. We couldn’t find anyone to play the part—it just seemed that nobody could do it. We hired Billy a little nervously, because he was a very young actor, and he turned out to be wonderful. And now here we were, all these years later, doing another show.

One thing about Ghosts is that, while it was in its time more controversial even than some of Ibsen’s other big plays, A Doll’s House or Enemy of the People, it’s revived much less often than those two. I think that may be because while we still have unequal marriages and environmental devastation, the things that made Ghosts so challenging for 19th-century audiences—anticlericism, infidelity, incest, syphilis—don’t hit as hard as they did then.

JACK: Au contraire! I had done this play at the Globe in the ’90s with Patricia Connolly and Richard Easton in the round, with not a dissimilar aesthetic. But this new staging has nothing whatsoever to do with that experience, because of Mark O’Rowe’s perspective, not only on the play but on the language of the play. You begin to realize how great the play is in terms of his mastery of dramatic situations, revealing one at a time how people are lying to each other. This was the first play where it’s all subtext. Ibsen said he had to write it because he wanted to write what happened to Nora when she left—that is Mrs. Alving. Suddenly you realize, this play is not about syphilis. It can be, if you don’t ask any questions of it. But it’s also about the value of truth and the responsibility to live in truth—which couldn’t be more relevant to what we’re all experiencing right now. So it’s like the scales have dropped off all our eyes working on this, because moment to moment, you begin to realize how complex the net of deception is.

It is one of the first modern plays, as you said, where the deadly secrets seep out to a big reveal and everyone’s implicated—a form that Arthur Miller and countless others would imitate.

JACK: No one did this before. We keep thinking of him as a sort of pompous, studious, “important” writer. No, he’s hot; he’s relevant. It’s an incredibly modern play.

André, you and others have described Jack as a great enthusiast, a flag waver. Does sound that right, Jack?

ANDRÉ: Wait till he reads my program note. They made me write one that was more personal because this was my last gasp, so I wrote just a little bit about Jack. I did call you the pied piper. I think of you as that. I said, “Where he goes, we follow happily.”

JACK: How lovely.

ANDRÉ: I meant that. Jack has an ability to inspire enthusiasm and confidence and admiration for a wide variety of things, both play-related and life-related, and you follow him irresistibly.

JACK: Oh, dear.

ANDRÉ: Well, I do anyway. I didn’t say you would lead us off a cliff.

JACK: Nor did you say I was working with rats!

I’ve read others say similar things about you, Jack—that you’ve been known to give your companies the equivalent of the St. Crispin’s Day “we happy few” speech to urge them on.

JACK: I was taught by masters: Ellis Rabb, Bill Ball, John Houseman, Eva Le Gallienne. Those were my teachers. In the early years in this extraordinary experiment of APA-Phoenix Rep, a small ensemble repertory, they couldn’t afford much of a staff, so I was the only assistant. For six years, I took the notes of Ellis Rabb, Stephen Porter, Alan Schneider, Eva Le Gallienne, and John Houseman. I learned as a young director to look at the stage as they did. You did not give a lighting note from an Eva Le Galllienne production to an Ellis Rabb designer. So I had an awareness that the directors bring a certain amount of their own aesthetic to bear; you are looking at a play through someone’s lens, right? That was the towering influence of my life, and I took that to the Globe.

The interesting thing is, directors don’t see other directors. We don’t work together. Musicians do, dancers do, actors do—obviously actors do, painters do. Not a director. We know about each other, but we have our own mojo and protection, and we don’t really know how the others do it. I did know how the others did it, because I had the most extraordinary, singular post-graduate degree of my generation.

So what’s the Jack O’Brien stamp on a production, if you had to define it?

JACK: I never know. I know that people have said to me that they could be led blindfolded into a production and know that it was mine. I don’t quite get that—and yet I kind of do. There are certain things that I gravitate to. Enthusiasm is one of them, yes, but also the sexual component—there has to be blood in the theatre, there has to be a pulse.

ANDRÉ: I think the other thing about you is the incredible variety of plays and musicals you’ve done. I mean, that this man has directed Henry IV and The Coast of Utopia and Hairspray and Shucked and many other things in between, new plays, all that—he just has this incredible ability to do various kinds of work, all very well. I don’t know too many other directors who I could quite say that about.

You’re very versatile.

JACK: That’s true, and this late in my career, I think the industry doesn’t really know where to put me. A perfect example: One of the most remarkable things we did was a play called The Nance, with Nathan Lane. André brought it to me and we did it, and we were incredible and an entire range of people in the production were nominated or won Tonys, but I wasn’t even nominated.

Were you upset?

JACK: It sort of amused me. I thought, they really don’t know where to put me. I do understand that; standing back, I don’t know where to put me either. Most people have a specialty. You know, Jerry Zaks has a kind of specialty; Joe Mantello, whom I adore, is a kind of director. I’m not any of those things.

The flip side is, if you’re versatile, you can work a lot.

JACK: The thing is that in the ’80s and ’90s, there were a bunch of us directors out there running companies: Dan Sullivan, Mark Lamos, myself, like Triple-A ball clubs. We were steering our ships according to our lens. If you run a theatre as a director, people fall out all the time; you’re planning a Twelfth Night, and John Rando was supposed to do it and then he gets a musical, so your business partner says, “It’s you!” So that’s what happened: Over 25 years, I did all sorts of stuff that I had to do, that I wouldn’t necessarily pick.

André, when Jack was talking about how he learned the trade, I wondered, where did you learn the ropes?

ANDRÉ: I don’t know; I’ve never been able to answer this. I’ve just always been interested in the theatre. I’m from New York, and I started going to the theatre when I was 5. It’s the only thing I’ve ever wanted to do. I spent a couple of early years in New York after college doing all kinds of crazy jobs, some of them theatrically related—like, I was briefly the head of the box office at the Delacorte, until I lost various important people’s tickets. I remember we were doing Two Gentlemen of Verona in the summer of ’71; it was a big hit, and Harold Prince, who was at the height of his career, was coming. Joe Papp wanted to get his ticket, so he went into the box office, which was then a trailer, and I had put the P under B, and so I couldn’t find Harold Prince’s tickets. I would constantly do that; picnic-goers would throw chicken bones at me because I couldn’t find their tickets.

Anyway, I did all these little jobs—I taught French, I worked for a record producer named Ben Bagley, I worked for a publishing house—but I was lost at 25 years old. I wanted to be in the theatre but I didn’t know people. I acted also; I studied for two years with Fred Kareman and Wynn Handman, and did some plays, but I was scared—as my psychiatrist used to say, I had trouble getting from the shadows to the spotlight. That’s actually been my biggest problem in life. I’m happy in the shadows and I’m happy in the spotlight, but getting to one from the other is very hard for me. Anyway, I had been cast in this tour of a play by Alan Bennett called Habeas Corpus, and playing the part that I always played, which was that of the neurotic young son…

JACK: Not much of a stretch.

ANDRÉ: In the meantime, I remember saying to my friend Leland Moss, who was a director, “I just don’t know what I’m doing; I need to be somewhere where there’s theatre.” He said, “Why don’t you go and see this guy who runs this scrappy little theatre Off-Off-Broadway, Bob Moss, at Playwrights Horizons; he’s just started operations and he needs help.” So I went to Playwrights Horizons and I had dinner with Bob Moss, who was very nice, and said, “You want to come here?” “Sure.” “What do you want to do?” “Anything.”

Playwrights had just moved to West 42nd Street, and it was a nightmare of horror—you can’t imagine what the street was like, it was a mess, full of prostitutes and massage parlors and everything. But the theatre was devoted to new American plays and producing their work and doing a lot every year—we used to do, like, 15 plays a year for very short runs, and I started volunteering for Bob and answering the phone, all that. Bob was so busy getting the place going that there were all these piles of manila envelopes with scripts that were sent to us. I said, “Bob, do you think I could read scripts for you, because no one’s reading the plays that are coming in, and maybe, do you think I could write a report?” He said, “Sure.” So I started reading plays and meeting young playwrights like Chris Durang and Wendy Wasserstein, just to name two at the time. I decided that I was going to give up this job in the tour of Habeas Corpus, because I thought, if I do that, I’ll never be able to come back to Playwrights Horizons again with the same head of steam. So I turned the tour down and never acted again. The tour actually folded quite quickly after that.

JACK: Directly as a result of your leaving it, I’m sure.

ANDRÉ: Hardly. I stayed at Playwrights Horizons and then eventually became the literary manager. Differently from Jack’s being influenced by these great people like Eva Le Gallienne and Ellis Rabb and John Houseman, I was a slightly different generation, slightly younger, and I was luckily the right person in the right place at the right time: I was starting my career into the unknown just the way the nonprofit theatre in New York was starting its career into the unknown.

JACK: All that is true, but you have specific and impeccable taste as a thinker, as an observer, as an editor. I don’t know anyone like you. So along with your own passion and your feeling lost back then, there was an element that distinguished you from other people. No wonder you were attracted to reading plays: You know what the argument of a play is, and you’re infallibly honest and clear about it. So what you found was a way for your own taste to become expressed, and that made the difference.

ANDRÉ: Yeah, I hadn’t thought of that.

JACK: It’s sort of hard to think about it oneself. Somebody has to say: That’s a lovely story, but you had fucking great taste.

ANDRÉ: In my younger days, one of my friends accused me of only picking plays with somebody like myself in the leading role. That, I believe, was not true.

JAKC: Well, it wasn’t true, but what was true is you heard the dramatic clarity of a character because you recognized it as your dilemma, and you knew that was dramatize-able, which many people don’t get. I mean, I’m fascinated now by the fact that every asshole thinks that every movie made can be a musical, and they can’t. They’re buying all these movies, and you think, no, a musical has to sing, right? There has to be some reason for the robot to sing, or it’s not a musical.

To close with a big question: Since you’ve both been in the business for a while, can you tell me, what is one of the biggest changes you’ve seen since you started?

JACK: Ticket prices. They’re killing us. I had dinner two nights ago with Manny Azenberg, and he said, “In the ’60s, a Broadway ticket was $15. I remember during a break in rehearsals for Le Gallienne’s Cherry Orchard, with Uta Hagen and Nancy Walker, somebody said, ‘Did you know that the Broadway price now is up to $23 for a ticket?’ There was a long pause, and Nancy Walker says bemusedly, ‘It’s hard to be $23 good every night.’” Now I’m told that tickets sell for between $500 and $700. Who are we doing this for? I have to say, I’m not a rich man, but I’ve done very well, and I can’t afford to go to the theatre. I think the defining problem right now economically is greed. We have out-priced ourselves, and I’m in despair.

André, your turn.

ANDRÉ: From my point of view, there are two things. One is that, for some reason, everything about putting on a production is much more complicated than I remember it being, even just 10 years ago. Everything you think can happen suddenly can’t happen, or has to happen a different way. I mean, everything changes. I don’t mean to sound like some old fogy; there’s a new generation here, and there’s a lack of knowledge about the theatre of the past. I’m not saying this critically, because every generation has different heroes and different variables. I’m not saying that a 25-year-old should idolize Carol Channing or Mary Martin, but they should know who they are.

I think my main thing, and I always say this to Jack, is that putting on plays, in my memory, which may be faulty, used to be fun, as well as difficult and complicated. It used to be fun, and it’s less fun; no one seems to be having as much—no one, not just me. Maybe I’m just thinking back to the early days of Playwrights Horizons, when it wasn’t so big and you could just put on a show, right?

JACK: You know who’s having fun right now? We are, downstairs. My Ghosts design team is there every day, all day. That’s never happened. These are young people. It’s vital, and we feel like we’re discovering something. We can’t wait to get to work.

Sure, nothing says fun like Ibsen’s Ghosts.

JACK: That’s always true, of course, when you stage something like this. You’re screaming with laughter—you have to, or you’d go stark staring mad.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.