SAN QUENTIN, CALIF.: I have seen at least a dozen productions of Macbeth in my life, reviewed most of them, and directed the play at both Utah’s and Colorado’s Shakespeare festivals. But I have never seen any performance of the Scottish Play as thrilling as the one mounted and performed inside California’s San Quentin Prison in late May.

Not that the production was anywhere near the level of the Royal Shakespeare Company, of course, or to that of a professional American theatre company, or even a graduate drama program. The production had no scenery, no curtains, and no focused stage lighting, and the vast majority of the cast had never before acted in a play, or, in most cases, even seen one—much less a play by William Shakespeare. There were plenty of awkward moves, muffed lines, and incomprehensible words. No, this is a play almost wholly acted by long-term prison inmates, all of them being what we usually call hardened male criminals.

They were hardly hardened when we met them. What is unique in this company is not its members’ place of lodging, but their energy, their commitment, and their extraordinary gentility, generosity and intelligence. They love their prison theatre group, they love their (female) directors, they love their invited outside audience, they love rehearsing their plays (which they do for a full eight months), and they adore Mr. William Shakespeare.

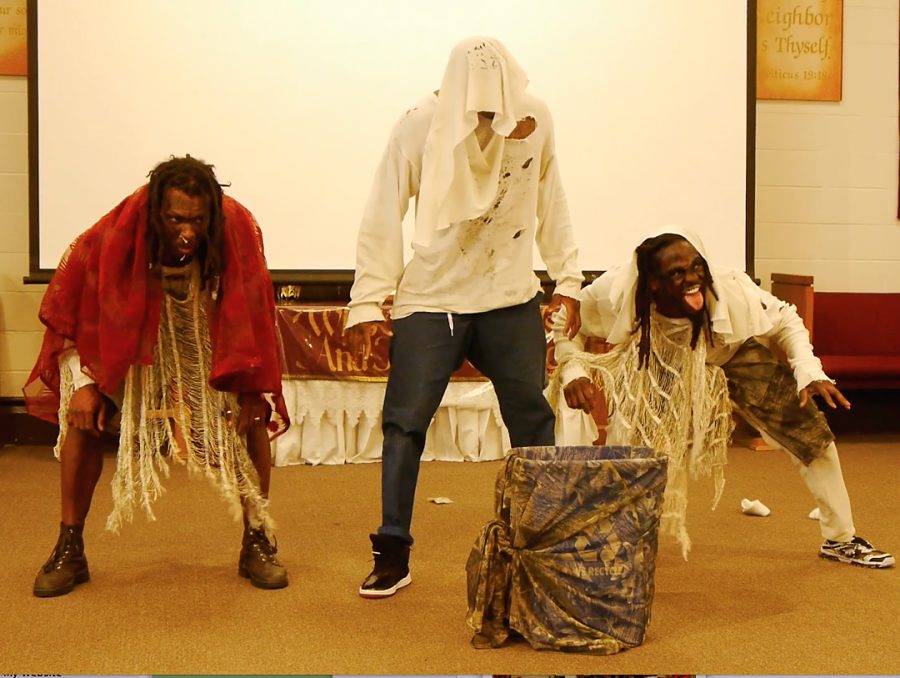

The principal director and script editor of this Macbeth was Lesley Currier, who with her husband Robert founded Marin Shakespeare Company in 1989. The company, just north of San Francisco, is only a few miles from the prison, and 14 years after its founding, Lesley began a modest acting workshop in the prison’s art studio. By 2008, the group began staging full-length Shakespearean productions in its 300-seat chapel. The minimal costumes and props (gilt paper for crowns, cardboard tubes for swords) are provided by Marin Shakespeare, and must be approved by prison staff far in advance of each performance; the inmate actors see them for the first time on the day of the performance, some of them using their creativity to enhance their costumes; the Macbeth spirits (they were not called witches here), for instance, ripped up their prison-issue white undershirts to appear “wild in their attire.”

Much of the excitement of the production came before it started. As outside guests, we entered—following a complex pattern of being searched, stamped, instructed, and shepherded into the Chapel by prison guards—to find many of the seats already occupied by dozens of prisoners scattered about, all dressed in identical bright blue shirts and trousers with the word PRISONER stamped vertically down their right legs.

The next thing we discovered is that we were seated among, and cheerily conversing with, the most lively audience members we’ve ever met—prisoners who turned out to be both joyous and intellectually vibrant, and passionate about acting, directing, and Shakespeare. Indeed, if it weren’t for the blue shirts and prisoner-identifying trousers, I would have assumed I was in the midst of a crowd of college students and their drama professors.

And maybe I was. The topic of the ensuing conversations—which lasted at least 90 minutes (as the cast had first been permitted into the chapel only the day before, and were now busily running through some of their moves, setting up their props, rehearsing their curtain call bows, and checking out their costumes)—was the prisoners’ delight in studying Shakespeare, acting Shakespeare, getting to know Shakespeare, and learning how to tell jokes without giggling. No one mentioned how they happened to be in prison, and no one in the audience would even believe they were in prison, had they not been wearing their identifications on their trousers.

This was not to belittle the performance that ensued, however. Quite the contrary: The entrance of the three all-black, all-male spirits, making a high-stamping entry down the center aisle from the back of the house, was stunningly choreographed by one Antwan Williams, and made even the most skeptical audience tremble with the wondrously pounding hurly-burly on the heath. The “bloody man” that followed, while his language was only intermittently comprehensible, had no trouble convincing us that his “gashes cry for help” when he was finally carried off the stage.

And Macbeth, played by Julian “Luke” Padgett—well, he was perhaps the most impressive Macbeth I have ever seen: terrifying when enraged, electrifying when penetratingly thoughtful, and inspiring when contemplative, soft-voiced and penitent. “I’m trying, man,” Padgett told me afterward. “I’m trying to be better. It’s not easy.” Padgett has lived in San Quentin for the last 20 years, serving time for “burglary, arson, car theft and first-degree murder.” No wonder he freaked out onstage (“We will proceed no further in this business…!”) when Lady M enticed him to go upstairs and kill the king.

Lady M, with her remarkably recitative tone, was a total treat. Played by the transgender Jarvis “Jae” Clark, her head half-shaved on the lower side and half-curled on the upper, her rotund body and “unsex me here!” proved a knockout for the crowd. I think I will remember her for the rest of my life. Macduff, Banquo, Duncan, Ross, the spirits, murderers, soldiers and apparitions—all were committed to their roles, committed to their fellow actors, devoted to their directors, and utterly memorable to their audiences. This was an unforgettable experience.

“What is gratitude and where do we find it when the last thing you hear at night is the loud click of your cell door being locked?” Julian Padgett wrote on a blog a few years back. “As a prisoner with the CDCR [California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation], I have seen many men with defeated spirits. Dead men walking, men who have been beaten down simply by their arduous years of incarceration. Individuals who believe their self-worth is less than zero. They enter not knowing what to expect, lost and unable to communicate their feelings in a manner that is healing and productive.

“Yet as time has gone by I also have witnessed growth in the character of these men. I have been in rehearsals with men who came in unable to read, but because of some invisible frequency that connected them to a scene in Shakespeare, they learned. These are the small moments where I am reminded that there is hope.

“Moreover, through this hope I find my own space where gratitude exists. Shakespeare has given me the necessary tools for living a productive life, not just tools for surviving. Next year will be my 20th year as a prisoner in CDCR, and seven of those years I have been acting with the Shakespeare program at San Quentin. And because of this program, I am a better man.”

Robert Cohen is the Claire Trevor Professor of Drama at the University of California–Irvine and a longtime professional director, translator, playwright, essayist, critic and author.