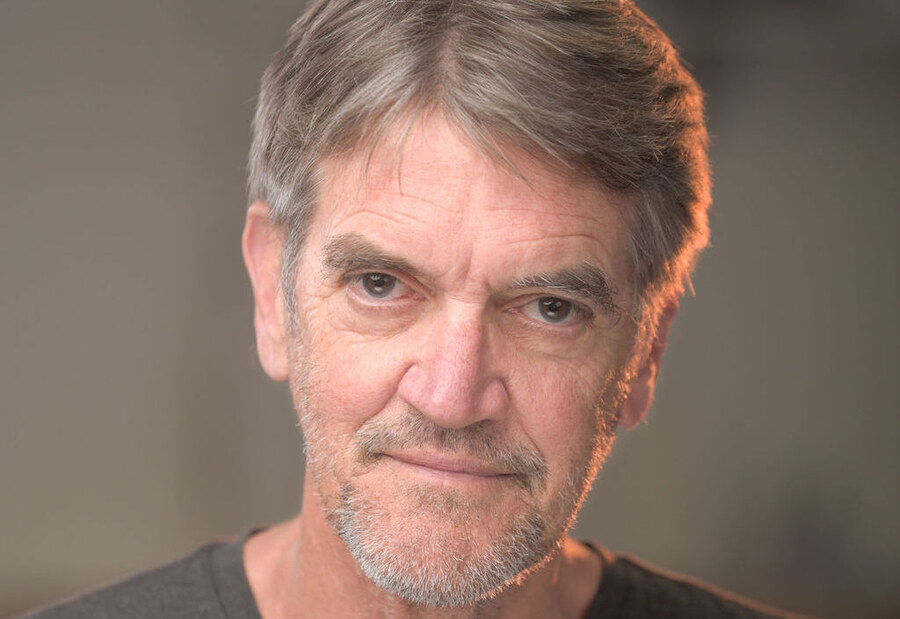

I met Chris Kayser more than 40 years ago, and I loved him from that day on.

Before he was an actor he was, among his legion of iterations, the most Catholic Buddhist this side of Thomas Merton. He was headed for the priesthood, seminary and all, when he was momentarily distracted by a short stint as a tennis pro.

But even then his spirit was more theatrical than athletic. He and another theatre legend, Jim Peck, would regale audiences who had come to see a sporting match with improvisational amusements. In one of them, Chris was a tennis pro from France who had developed a version of Prof. Harold Hill’s “Think System,” in which Chris taught the local groundskeeper (Peck in disguise) to play a perfect tennis game in five minutes just by thinking his way into the ball’s spiritual center.

Chris was my favorite actor, an opinion I share with Mick Jagger. Chris was in a movie called Freejack; Jagger was the bad guy and Chris was his henchman. After the first day of shooting, Jagger came to Chris and said something like, “How do you do that?” By which he meant, “Why are you so good?” So Chris gave Mick a few ideas, and now look: Just about everybody has heard of Mick Jagger, mostly thanks, I think, to Chris’s ministrations.

We met—Chris and I, not me and Mick—at the Academy Theatre in Atlanta. He was a company member and I was their kind-of-resident musical director. One of our first shows together at that theatre was Strider, in which Chris played the titular role, a horse. It was a musical featuring singing horses. On the first day of rehearsal, Chris came in knowing all the music and told me he’d figured out how to approach it. He then sang one of the songs—the entire song—as Mr. Ed, the talking television horse.

Only a few years after that, he was Boxer, another horse, in the musical version of Animal Farm. Boxer’s repeated mantra was “I will work harder,” which, everyone agreed, was Chris’s constant sentiment in life and in art. The production required the actors to wear head masks, a little like the ones in The Lion King, only less elaborate. Early in the run another actor got their mask caught on the chicken coop and couldn’t get loose. So when Chris said, “I will work harder,” the trapped actor whispered, “Could you work a little harder to get me loose?” As he continued his dialog, Chris moved—horse-like and majestic—toward his cohort and, with a flick of his casual hand, freed the other actor’s mask. Unfortunately that caused one of the eyeballs in the just-freed mask to pop out. It bounced, like a ping pong ball, across the stage and out into the audience. Chris offered his sympathy with a shrug and kept right on singing while the rest of the cast dissolved in laughter.

Over the years Chris and I worked on, conservatively, five billion projects. He wrote a new translation of No Exit for another Atlanta theatre, Theatrical Outfit, when I was the artistic director there. His French was that good. He performed in France lots of times and in the French language theatre, Théâtre du Rêve, in Atlanta, but his ability to translate Sartre was astonishing.

He was also the most athletic Beowulf I’ve ever seen in the only show the Outfit ever held over while I was there. His agility as that character was dance-like, and his approach was fearless. When the choreographer asked him to dive off a table into a sea of actors, he flew. When he was asked to wrestle a 10-foot-tall Grendel, he dazzled. And when it came time for him to sing one of the warrior songs, his voice pierced the veil between theatre and reality.

Not content with flying, singing, and astounding feats of derring-do, Chris was also a starring member of a comedy troupe called, I kid you not, Joke Rodeo. My favorite of his sketches in that ensemble featured him as an obsequious French waiter. It started with, “Excellent choice, Monsieur, the soup is sublime,” and progressed to telling the diner, “I love you, Monsieur. Oh, not as much as some, but give it time, it may grow.” He made a two-minute bit out of the squeaking noise a cork made coming out of a wine bottle that was one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen. I laughed so hard that I couldn’t breathe and had to go outside for a minute.

One of his most recognized roles was as Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, first at the Academy Theatre, then at Atlanta’s big house, the Alliance. All told, he was in, conservatively, one billion productions of that play. Every time he was in it, he approached Scrooge just a little differently. Sure, he went from soulless miser to joyous celebrant with ease and grace, but there was always something better in each successive version. Because he would work harder. In one particularly challenging rendering of the character, he was required to fall from a very high place onstage into a blanket held by 10 or 12 cast members, with no other safety precaution. He did it every night for a five-week run—even at the school show when several of the audience members were throwing pennies at the actors as they stood holding the blanket.

So there’s at least one of the metaphors for Chris’s life: A leap of faith was a daily occurrence for him.

For years he and I talked about the metaphysics of theatre. He believed, as I do, in the concept of līlā, the Sanskrit word that means “life” but is often translated as “the play in God’s mind.” Theatre is the truest metaphor for life. Ask anybody. Start with Aristotle or Shakespeare or anybody you like. We all know we’re just actors here.

In recent years, as Chris grew less interested in the Catholic church, his thoughts turned to other spiritual pursuits, as did our near-daily conversations in the woods together. We reminded each other of the Buddhist story about a person hanging on the side of a cliff: There’s a hungry tiger up above and another hungry tiger below, but instead of tigers, all this person can think about is the grapevine that they’re holding onto in the immediate moment, and how delicious the grapes are.

After he found out about his illness, that particular story took on constant daily meaning, and he carpe’d the hell out of the diem. He first took Buddhist vows. After that, not content with examining his own spirit, he also took vows as a bodhisattva—someone who, out of compassion for all sentient beings, refrains from entering nirvana in order to first help others.

Best of all, in the past couple of years it’s been my great joy to play music with Chris. We were in a very odd jug band together. He sang, played guitar and harmonica, and generally behaved in a ridiculous, outrageous manner in front of adoring loved ones and fans. He put on, excuse my language, an antic disposition. It was just another version of his other outrageous displays as a tennis pro or an actor or a translator or a seminary student or laughing Buddhist.

For the first few days after he was gone, I couldn’t talk. I wasn’t sure I was breathing, exactly. I didn’t know what to say or do. Three nights ago I got lost driving home from a place two miles from my house in a town where I’ve lived all my life. I was incoherent and witless.

Now I’m just grateful that I knew Chris so well for so long. And I believe the great heavy sadness that dropped me down for a minute is now gone. I can taste the grapes and ignore the tigers. Because somewhere out there is a bodhisattva who’s working harder, working overtime, to help me out. So thanks for that, Chris. I’ll see you in the green room.

Phillip DePoy is an Edgar Award-winning author, playwright, and scholar. His more than 20 novels include the Fever Devlin series and the Christopher Marlowe mysteries. He lives in Decatur, Georgia.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.