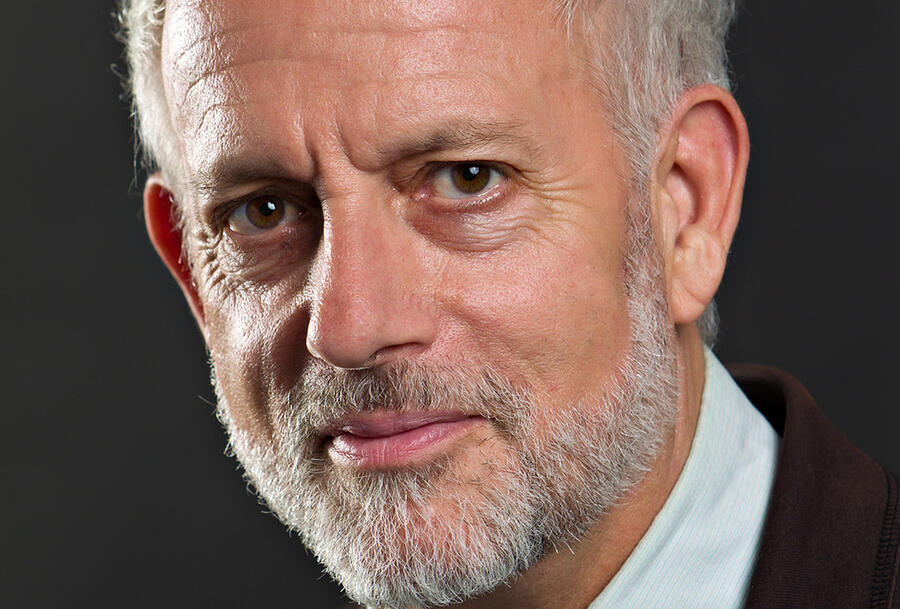

David H. Schweizer, a director of theatre and opera known for his work in Los Angeles, Off-Broadway, and internationally—including works by John Fleck, Sandra Tsing Loh, Ann Magnuson, Michael Sargent, Justin Tanner, Rinde Eckert, Charles Mee Jr., and Jean-Claude van Itallie—died on Dec. 5. He was 74.

“Nothing human disgusts me.” Those are the words of Hannah Jelkes in Tennessee Williams’s gorgeous paean to the dissolute and disenchanted, Night of the Iguana. I was 17 when I did my first community theatre play, cast as Pedro, the iguana-wrestling cabaña boy among a troupe of seasoned, semi-professional actors, but those words have been tattooed on my soul ever since. They were amplified again decades later by my friend and frequent collaborator Jan Munroe in his unforgettable elegy to his recently deceased father.

Today, writing barely 24 hours after the death of my lifelong friend, mentor, and convention-defying director David Schweizer, I find that sentence worth challenging. How could anyone not be disgusted by such a life cut short—a life so rich, so wide in its influence, so dedicated to making art despite hardships and adversity, so embracing of a vast diversity of actors, writers, designers, and producers, that the very notion of community builder must be included on his epitaph? Those of us who continue to make theatre know the significance of that role.

Six years after my first foray into Williams’s oeuvre, at 23, I was part of a small group of apprentices at Arena Stage in D.C. We piled into a car and drove up to NYC to audition for Williamstown. By then, I had already begun exorcising some of the demons that held sway over me. Most significantly, as Shakespeare’s Caliban, I had given body, voice, and untapped fury to the monster I believed I’d kept hidden. That was the monologue I chose to show David in that first audition, also our first meeting.

Stripping off my shirt, climbing on the boardroom-style table, I beat my bare chest and roared,

When thou cam’st first

Thou strok’st me and made much of me; Wouldst give me

Water with berries in’t; and teach me how to name

The bigger light, and how the less,

That burn by day and night; and then I loved thee…

Cursed be I that did so!

David’s eyes sparkled with the glee familiar to those of us who’ve worked with him. Practicing professional restraint, head nodding with approval as he would often do when considering his next, calculated move, he took a deep breath and said, “I’d like you to stick around to meet Nikos,” meaning Nikos Psacharopoulos, Williamstown’s co-founding leader.

I did, of course, and spent the next two summers at the festival, first under David’s tutelage in the second company, followed by the season of ’77, when I graduated to the mainstage and got my Equity card. My welcome mat to the professional theatre was laid at my feet by David Schweizer.

That was just the beginning. The following year, as I was graduating from the advanced acting program at Juilliard, David called from California to say, “I’m directing Len Jenkin’s Kid Twist at Gordon Davidson’s Taper Too, and I need you for several roles. This week.” To which I said, “Great, graduation is this Friday, I can be there Saturday, okay?” To which he replied, “No, I need you here Wednesday.” I skipped graduation.

I moved to L.A., where I’ve remained for the past 46 years. Over the course of time here, I’ve built a career as an actor, writer, director, producer, co-artistic director, and teacher—the trades we dyed-in-the-wool theatremakers ply. Through all of that, the single most consistent creative relationship I’ve maintained other than with my husband was with Schnitzelbrain (David’s personal moniker). Without hesitation, he would summon me, or answer the call when I needed him, craved his advice, or relied on his skills, his sense of humor, his intelligence. We worked together on my own material, brand new work by others, and classics, and not only in large and small theatres in Los Angeles as a member of his Modern Artists Company, but Off-Broadway and in London as well.

Today, as I tried pushing through my grief at this unacceptable departure, I attempted to count the shows we’ve done together. All’s Well That Ends Well, Kafka’s Amerika, Kid Twist, Plato’s Symposium (four incarnations, including at the ICA in London and the Getty Center), Peer Gynt, Marlane Meyer’s Kingfish (at the LA Theatre Center and Joe Papp’s Public Theatre), as well as her Geography of Luck, Stravinsky’s A Soldiers’ Tale, and my own Cologne (in L.A., Ojai, Santa Fe, and at NY’s Rattlestick). For that last show, David’s dramaturgy—which involved taking my published novella and sculpting its literary heft down to the essential, actionable components that made it fly—was peerless.

Typing these titles out now awakens me to something beyond word counts: This is four and a half decades of collaborative work, and not just with me—he worked with multitudes. My God, how have we not made Knights of the Empire out of such efforts? Isn’t that an exemplary record of community building? Isn’t that a shining case—along with medical workers, teachers, journalists, war-torn relief workers, artists, musicians, etc.—of what civilization is capable of? Does the work of artists like David only register with a small circle of intimates? If so, then I sing in praise of that circle of heroes who make sure that we are the beneficiaries of art and culture.

Tonight, I sing the life of David H. Schweizer. He taught me how human I could be. Nothing about my humanness disgusted him. He helped me carry any value I have into the greater world, and past the lesser one. In a Los Angeles Times article about my work, David was quoted as saying, “The best thing I did for Los Angeles was bringing Tony Abatemarco here.” No, David: You were the best thing. I, along with so many others, simply gained by your belief in us.

In his last years, his partner, Caleb Wertenbaker, provided further extensions of his art into opera, often designing those beautiful forays as well as helping David relax into an enduring domestic life. David was cared for on a level he’d cared for others. There’s comfort in knowing that he’d found that solace, that grace. (Thank you, Caleb.)

So…Flights of angels and rest in peace, dear friend of my heart, blood-brother of my art. Our birthdays are six days apart. I will never not wish you happiness.

Tony Abatemarco is a writer and director.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.