James Earl Jones, the acclaimed actor who made his name onstage in The Great White Hope, Boesman and Lena, Fences, and countless other plays, including Othello, died on Sept. 9. He was 93.

It was in the spring of my sophomore year at Howard University. As I was leaving class, I heard a group of female students in a flutter. “He’s here!” “Did you see him? I’d heard that he was coming, but I didn’t think it was today!” “Well, it is today! He is here and he is magnificent!”

I had no idea of who had caused such commotion, but as I approached the exit, peering through

the glass doors, I saw him: Mr. James Earl Jones.

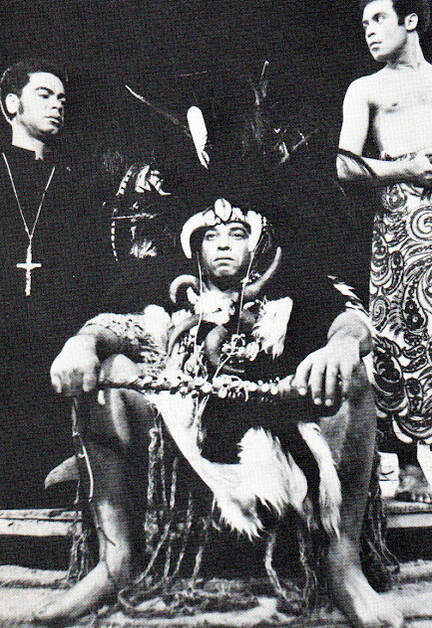

The Great White Hope was in its pre-Broadway performance run at Arena Stage. He had taken time out of his theatre schedule to visit this historic institution of higher learning; and yes, he was magnificent! Statuesque, handsome, and strong, with an air of gentleness about him.

Fast forward to post-graduation, living in New York City. A friend had tickets to see the Broadway production of Lorraine Hansberry’s Les Blancs. Following the performance, we were allowed to visit Mr. Jones in his dressing room. He was very kind to receive us. My friend asked all the questions. He noted that, and with a smile turned to me and said, “You don’t speak much.” “Well,” I said, “my mother taught me that there were two times when one should be silent: When you have nothing to say, and when it’s not your turn.” He laughed at that.

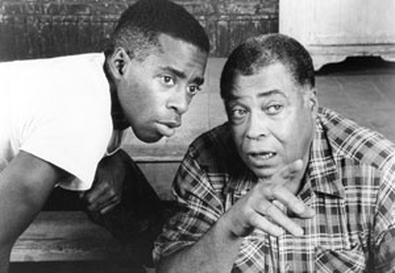

More than 30 years would pass before we would perform in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Playing Big Mama opposite his Big Daddy, under the direction of my sister, Debbie Allen Nixon, had been beyond my dreams. But there we were in the rehearsal space, working it out together.

When I am asked, “How was working with James Earl Jones? What was his process? What was he like?” I pause before answering. My first observation was his interest in the “sinews” of thought. Pondering and probing the complexity of human behavior, asking questions of himself that few artists would consider, he’d come to one thought or question that he deemed most important in understanding who the person/character was; he would pursue that thought or question throughout rehearsals and performances. He had to be in the heart of the character. I would learn more about this later when we would speak about August Wilson and his portrayal of Troy Maxson in Fences.

His focus was relaxed, his level of concentration was astounding. Of everyone involved in the production (Tony, Golden Globe, and Emmy winners and an Oscar nominee among them), Mr. Jones was clearly the most seasoned and the most gracious. This was Debbie’s Broadway directorial debut. He adored her, and listened with rapt attention to everything that she had to say, eager to explore her suggestions while offering his own. Debbie enjoyed improvisation as a means of discovering “what lies beneath the written page.” Mr. Jones said, “I don’t know. I don’t do well with improvisation. I’ve never been good at it, but okay, I’ll try it!” He tried it and he liked it.

Mr. Jones was a “living legend,” and we all knew it. But this iconic status—well deserved by virtue of decades of sustained excellence in performance onstage, in film, and on television—did not preclude normal interactions with people. Being with Mr. Jones was easy because of his genuine interest in each person that he met. He was present, kind, and accessible.

During the time of our work together, through casual conversations, James Earl (as I had come to call him) would share life experience and reflections: the trauma of separation from his parents at the age of 5 years old, which resulted in stuttering; the embarrassment and anguish at being mocked that was the reason for several years of self-imposed silence; the study of poetry that led to discovery of his capacity for clear, unobstructed speech.

His high school English teacher gave an assignment for students to write a poem. James Earl wrote “Ode to a Grapefruit.” Students were required to read their poems aloud to the full class. The inevitability of being mocked for stuttering was terrifying; but there was no way out. He stood before the class to read his poem, knowing that it would be a disaster; but to his surprise, there was no stutter. His speech was free! Speaking the written word aloud became a pathway forward.

We spoke about many things. Our conversations were always interesting. One centered around Troy Maxson in August Wilson’s Fences. We spoke about the language of the play; how Wilson had captured rhythmic speech. James Earl said that in his early years as an actor, it was his father, the actor Robert Earl Jones, who told him to remember his Southern roots, because “the time will come when people forget this way of speaking and you won’t be able to teach them.” When I asked about his approach to developing the character, he simply shared this reflection, “Lord, forgive me for wanting so much; but I am so wanting.” He continued by saying that the most important thing for him to know about Troy was if he was really capable of killing his son. He never answered that question–not to me, at least. If Troy Maxson had been capable of murdering his own son, it would have been completely antithetical to James Earl’s thinking and way of life.

What mattered most in life to James Earl Jones was his family. He treasured his wife, Cecilia, and his son, Flynn Earl. He was passionate about his work, relished the creative process, and valued his friends and professional associates. He was compassionate, non-judgmental, knowledgeable about many subjects, well-versed in literature, critically acclaimed as an artist, revered as a human being.

Phylicia Rashad is an Emmy- and Tony-winning actor and director.