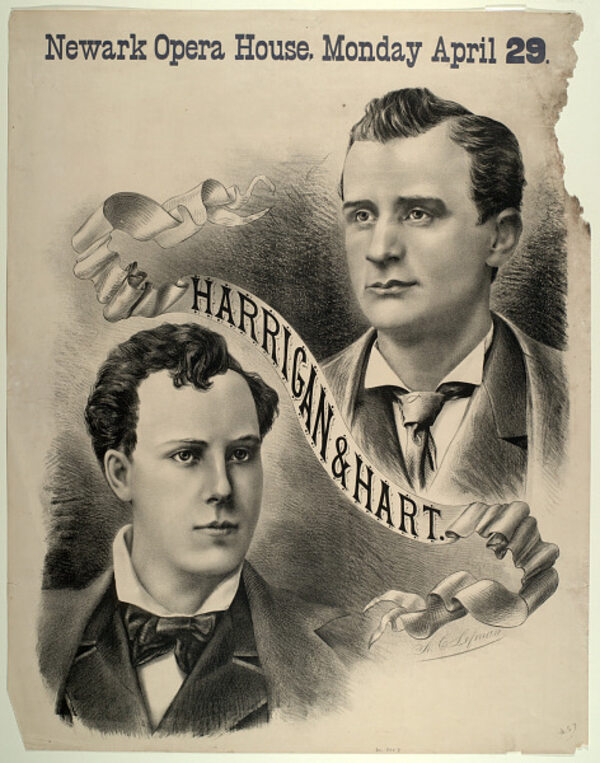

1874 (150 years ago)

The song “Muldoon, the Solid Man,” written by Edward Harrigan, was first performed by Harrigan and his stage partner, Anthony “Tony” Hart, on Monday, March 2, 1874 at the Theatre Comique in New York City. Originally performed as part of the musical comedy Who Owns the Clothes Line?, “Muldoon, the Solid Man” became one of the most popular songs performed by Harrigan and Hart. Today the song is the only real Harrigan work that continues to be performed and covered by contemporary artists. From 1871 to 1885, Harrigan and Hart were wildly popular comedians and musicians who assembled musical comedies together based on a range of racial stereotypes. Hart was a performer, while Harrigan wrote book, lyrics, and often music to more than 300 songs. Their performances, exemplified in “Muldoon, the Solid Man,” often presented Irish working-class immigrants as comic caricatures, but their transition from variety shows and vaudeville to more integrated musical comedies helped to lay groundwork for the development of the American musical.

1894 (130 years ago)

In Lillington, N.C., playwright Paul Eliot Green was born on March 17. Green won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for In Abraham’s Bosom (1926), a tragedy about a mixed-race farmer who struggles against Jim Crow-era segregation and ultimately is driven to murder. A professor of philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Green worked with Richard Wright to adapt Wright’s Native Son, produced and directed by Orson Welles, at the St. James Theatre in 1941. Green is perhaps best known today as the playwright of The Lost Colony, an outdoor musical performance originally billed as a “Symphonic Drama under the stars” depicting the mysterious disappearance of the English colonists of Roanoke Island in 1590. The Lost Colony began running in 1937 as part of the Federal Theatre Project and has continued ever since in Roanoke Island, N.C., with interruptions during World War II and the COVID-19 pandemic. Green was named the North Carolina Dramatist Laureate in 1979 before his death in 1981, and he was inducted in the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame in 1996.

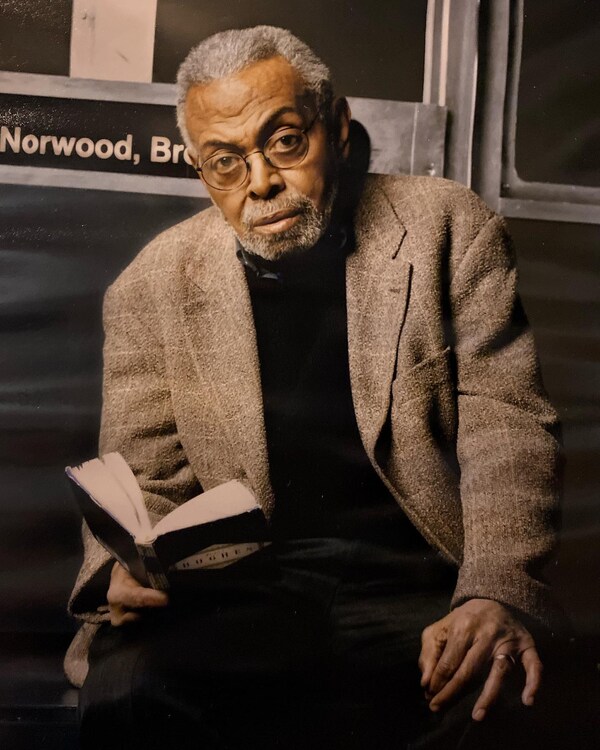

1964 (60 years ago)

On March 24, Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman opened at the Cherry Lane Theatre in New York. Set in a subway car that serves as a symbol for the personal prejudice and systemic oppression that Black men face in the United States, the play, according to Baraka, depicts “the kind of seduction the Black middle class, particularly Black intellectuals, experience.” The one-act drama—the last play Baraka wrote under his former name, LeRoi Jones—won an Obie Award as “Best American Play” of 1964. Dutchman is one of Baraka’s most significant early works, with its interweaving approach to realism and surrealism, as well as its shocking conclusion, establishing him as a major playwright. Produced a year before Baraka opened the Black Arts Repertory Theatre in Harlem, Dutchman represents a precursor of the work that came soon thereafter in the Black Arts Movement. The play was adapted into a 1966 film directed by Anthony Harvey, starring Al Freeman Jr. and Shirley Knight. The first Off-Broadway revival of the play came in 2007, again at the Cherry Lane Theatre, starring Dulé Hill and Jennifer Mudge, directed by Bill Duke.

1969 (55 years ago)

At a New York symposium called “Theatre or Therapy?,” a band of supporters of the Living Theatre, including acting company members, physically disrupted the proceedings. Robert Brustein, then the artistic director of Yale Repertory Theatre, had recently published an article in the New York Review of Books that decried the Living Theatre for its “mindlessness, humorlessness, and romantic revolutionary rhetoric” during its recent U.S. tour of four shows, The Mysteries and Smaller Pieces, Antigone, Frankenstein, and Paradise Now. Julian Beck and Judith Malina, Living Theatre co-founders, had been arrested by New Haven police in 1968 after performing Paradise Now at Yale the year before. The symposium was organized by Theatre for Ideas, a private salon organized by Shirley Broughton in 1961 to promote innovation in theatre, and included Brustein and social critic Paul Goodman alongside Beck and Malina. “Theatre or Therapy?” quickly “broke down into chaos,” according to The New York Times, as Living Theatre supporters began heckling Brustein, shouting from the balcony before descending onto the stage, pounding on railings, screaming, and spitting into the faces of other audience members calling for order. This disruption represented a climactic moment in the tension between the avant-garde theatremakers and Brustein. The Living Theatre soon after began working on The Legacy of Cain, a collaborative play cycle that was performed in public spaces away from typical theatre venues that became the focus of their work in the 1970s.

1989 (35 years ago)

And What of the Night?, a tetralogy of short plays by Cuban American playwright María Irene Fornés, opened at Milwaukee Repertory Theatre as part of the inauguration of their new black box theatre. And What of the Night?‘s four short plays followed the same intergenerational characters. While the plays are narratively ordered as Nadine, Springtime, Lust, and Hunger, Fornés wrote them in a different order over the course of four years. Fornés, who also directed the project, had started writing the first of the four, The Mothers (retitled to Charlie, and then finally Nadine), in 1986. In 1988, Fornés was commissioned by En Garde Arts to write Hunger for an empty warehouse space in West SoHo that was about to be converted into an office building. When approached by Milwaukee Repertory Theatre for a separate commission later that year, Fornés imagined two plays that took place between The Mothers and Hunger, using the same characters, which became Springtime and Lust. An epic and disturbing journey chronicling the pernicious effects of poverty, illness, and crime, And What of the Night? critiqued what Fornés described in a 1990 program note for the Trinity Repertory Company production as “the outcome of our mindlessness and heartlessness.” Originally titled Give Us This Day, Fornés’ tetralogy became a finalist for the 1990 Pulitzer Prize and was first published in 1993 as What of the Night?