Remember the early years of Twitter, when it still seemed novel to communicate and even form friendships with people you’d never met in person? When hate speech and disinformation, though not absent, were less prominent in our feeds?

This was the social media landscape that Emmy-winning actress Dana Delany (China Beach, Desperate Housewives) stepped into in the early 2010s, when she was working on ABC’s Body of Proof and was asked to join Twitter to promote the show. Little did she know that this work task would lead to an extraordinary online friendship with a young fan that would spiral into a stranger-than-fiction tale.

Half a decade later, this story captured the imaginations of playwright Jen Silverman and director Mike Donahue, who had worked with Delany on Silverman’s Collective Rage: A Play in Five Betties, in 2018. The trio was on a train to see another of Silverman and Donahue’s collaborations at New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre when Delany’s peculiar experience came up in conversation. “Our jaws were on the floor,” Donahue recalled. “It was such an incredibly fascinating, riveting story.”

Silverman and Donahue immediately recognized the dramatic potential in Delany’s account and were pleased to learn that she had already been contemplating how it might work onstage. After bringing on board Tony-nominated scenic designer Dane Laffrey—a frequent artistic partner of Silverman and Donahue who had also worked on Collective Rage—the team of four co-creators began a four-year process of transforming Delany’s Twitter archive into the play Highway Patrol, now at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre through Feb. 18.

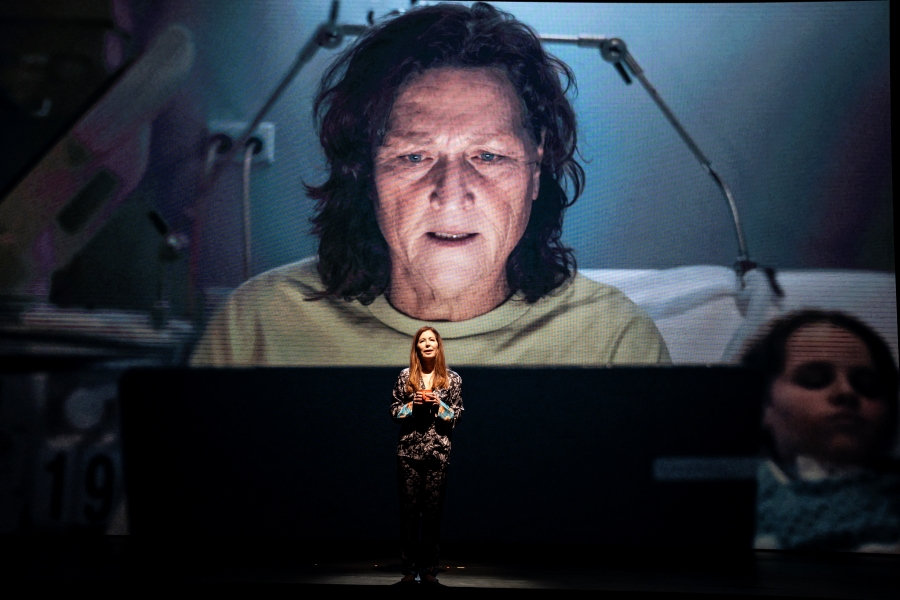

Billed as a thriller that is part love story, part ghost story, Highway Patrol stars Delany as herself alongside Chicago actor Thomas Murphy Molony as 13-year-old Cam and Dot-Marie Jones (Glee’s Coach Beiste) as his grandmother and other characters. In this true story, Cam—a seriously ill kid who has undergone multiple heart transplants—reaches out to Dana on Twitter, and the two strike up a correspondence over direct messages.

In the midst of a grueling and isolating filming schedule, Dana soon finds herself communicating with Cam at all hours and even gets to know members of his family. What begins with lighthearted exchanges of songs and video links deepens into a friendship in which Cam can discuss his fears of dying with an empathetic listener; in return, he does his best to cheer Dana up when he thinks she’s feeling down. But the relationship takes quite a turn as Cam gets sicker and begins to have visions, bringing Dana uncanny messages from the beyond.

“Basically, this relationship that Dana had developed with this kid and with his family started taking them all to places that were completely unexpected and strange and mysterious and beautiful and a little bit shocking,” Silverman said, careful to avoid spoiling any of the show’s major reveals. Running parallel to the intriguing plot twists is a moving human story, Silverman added. “At its heart, for me, this is so much a story of intimacy and connection and our desire to connect to another human,” Silverman said.

Creating a satisfying theatrical experience from such unconventional source material was no small feat. While they all share the title of co-creator, each of the four has specific roles: Silverman as playwright and text curator, Donahue as director, Laffrey as designer, and Delany as actor, and, of course, inspiration for the entire project. Nevertheless, they have worked as a team throughout the process, each contributing ideas to various aspects of the show. “We are very fluid with our boundaries,” said Silverman.

In an early workshop at New Dramatists, the co-creators sat down with a big binder filled with printed copies of Delany’s digital archive—tweets, direct messages, emails, photos—and read straight through it with several actor friends. “Even with that vast amount of unshaped material, there was such a heartbeat to it,” Silverman recalled. “It was so theatrical and so exciting and so weird that we were like, there is something here, and now we have to excavate it.”

The excavation progressed in several phases, each requiring different tools. “For a while, these were tools that I was wielding of curation, of cutting, of moving, of juxtaposition—building a spine, building a theatrical engine, building a set of ways in which the story unfolded,” said Silverman, “but trying very hard not to add or change language—subtract it, for sure, but just really building with what there was.”

When it became clear that the archival material alone wouldn’t create a cohesive narrative, Delany’s collaborators interviewed her to provide additional context and fill in gaps. These interviews provided language that would become direct addresses to the audience in the current version of the play, with the goal of better communicating her personal perspective. (Delany was unavailable to interview for this article.)

Over the past year of development, the creators have employed “more traditional theatrical tools,” said Silverman. This has required looking at the text as if it were not in conversation with an archive and determining where certain beats are needed or where a character’s motivation could be better explored.

“The story we are telling is, beat by beat, a true story,” said Silverman. “There are moments in which we’ve had to get theatrical and inventive around how that plays out and what the audience is encountering. And in places, we’ve made guesses about what a character would have been thinking and feeling based on what it is that they said.”

Once rehearsals began, the play continued to develop in new ways. “So much of what is actually happening in the play is not communicated explicitly in the messages that [Delany and Cam] are sending one another,” said Donahue, “because, of course, especially when you’re building a new relationship and it’s with somebody you don’t actually see in the real world, you have the ability to control what you do and don’t share with that person.”

An important part of the rehearsal process has been finding ways to communicate “the particular kind of isolation and loneliness and need for connection” that Delany was experiencing at the time, Donahue continued. “None of that is stuff that she’s talking about with that kid. But it’s all in there, once you land that context for the audience. So a lot of the process has been about figuring out how to tell the story visually and physically so as to make that human experience accessible.”

Since the play is about an online relationship, the designs naturally include an “omnipresent multimedia element,” said Laffrey. “But it was also very important that this piece feels really dramatically satisfying, and we’re structuring it a bit like a thriller, so it really, really didn’t want to feel like Dana Delany doing a TED Talk. We’re working to cut against what it means to put a human in front of a big video screen and all the semiotic things that brings up for an audience.”

Barely a decade on from when the play is set, social media occupies a much more complicated place in our public and private lives in 2024. So much has changed that it almost sounds quaint to refer to “Twitter” rather than “the company formerly known as Twitter.” Still, the co-creators of Highway Patrol find value in this wholesome if strange story of two unlikely people connecting online.

“For all the ways in which the internet can be really dangerous or scary or politicized, and sort of an outrage machine, the idea of the internet in the piece is that, ultimately, it’s a tool for connection and that it’s a way for people who are profoundly lonely and isolated in the world to find one another,” said Donahue. “I think this play is actually very much about the potential for humanity in the technology.”

It was this sense of humanity that drew Silverman to Delany’s story in the first place. “The optimism and the generosity and the openness with which Dana received this kid and his family into her life and also with which she received a set of possibilities that the world could be much different and more mysterious, and in some ways more beautiful than perhaps she had thought—that really speaks to me,” said Silverman. “That also feels like a conversation that we could use now.”

Emily McClanathan (she/her) is a Chicago-based writer whose work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Reader, Playbill, TheaterMania, Theatrely, and more. She is a 2020 National Critics Institute Fellow.