In English, people laugh with “haha,” in Spanish with “jaja,” and in Brazilian Portuguese we “kkkkk.” It aches, it’s warm, and it’s embodied—a loud, back-of-the-throat, whole-spirited laugh that bends over and reaches for harsher consonants. In my patria Brazil, you see this kind of sensibility at every gathering: Even at the theatre, vendors sell candy with the same enthusiastic cheers you’ll hear at street markets or on beaches, actors constantly break the fourth wall to interact, and people of all ages howl in joy. The language itself cracks open in joy and relief, as the politics of theatre are a-changing.

In recent years, a shared Latin American history of censorship and jarring socioeconomic divides have impeded full arts engagement, in spite of a naturally theatrical culture. As, over the past year, more and more U.S. companies have been reporting discouraging audience retention rates and major shifts to accommodate the return to in-person programming, I wondered how complexities around Brazilian culture, politics, health, and economy would play into its theatre scene—and what that might reveal for other nations.

Specifically, how has the public’s relationship with live theatre shifted? Where is theatre in Brazil headed? One could fill volumes with a truly comprehensive analysis of such a big question in such a large nation. But after visiting family and theatres in 2023 and talking with several directors, I’ve focused here on a few major players as a way to examine wider trends. These creatives’ wisdom reaffirms in me not only pride in Brazil’s resilience, but also my conviction around the need for more international exchange.

A nexus for theatremakers from all over, the enormous Festival de Curitiba in Paraná, in the nation’s south region, champions a promising vision of Brazilian and international theatre every fall (March-April). Inaugurating the beautiful Ópera de Arame with its opening in 1992, the festival represents a major hub for both the city of Curitiba and for Brazilian culture at large. The largest performing arts festival in Latin America, it directly hires approximately 600 people, and over a 31-year history has brought more than 3 million people together for 5,000 shows from hundreds of local and international companies. Organizers shared an astonishing statistic with me: Their return to in-person programming saw attendance go up by 20 percent, compared to pre-pandemic numbers, with 200,000 audience members showing up in 2023. Festival director Fabíula Passini said that multiple venues frequently sold out on the same night. She credited this influx to such factors as Brazilian culture’s propensity toward word of mouth, people’s eagerness to experience live events, more intentional accessibility arrangements, and targeted community outreach.

“We take care with marketing that includes everyone, especially centering people who don’t go to the theatre,” Passini said. “Our agreement with company sponsors includes incentivizing workers to attend, with free tickets and us going in to culturally mediate. We’ll prepare them by sharing what the festival will look like so they know what to expect, instead of feeling like the space might not be for them. There are many people who feel hesitant about attending theatre, so we’ll go to different groups and communities outside those companies as well. We talk with the public which doesn’t usually see theatre, and the whole year they look to the festival with anticipation.”

Across 13 days starting in March, theatrical experiences are presented in seven main categories: Mostra Lucia Camargo (international space for cutting-edge new work and adaptations), Interlocuções (free cultural panels and workshops), Fringe! (often experimental works from growing Brazilian groups), Mish Mash (theatre with music for all ages), Risorama (a comedy festival with big names like Diogo Portugal), Guritiba (the Theatre for Young Audiences division), and Gastromix (an intersection between culinary and musical experience). I can say from experience that in Brazil we love to gather people with food and to uplift children, so it’s no surprise these last two features attract great numbers.

Passini added that the festival’s efforts to welcome diverse audiences introduce people to different genres; they might come for the comedies and stay for the experimental plays. But she ensures there will be something for everyone and deeply considers when shows should be performed on streets for access and exposure. One memorable instance, she shared, came when Mundana Refugi, an orchestra comprising both refugees and Brazilians, played in a public, open-air space on a weekday just as people were getting home from work. Audience reactions as they crowded around reminded Passini of the power and potential in the live performing arts—if we dig deeper into audience relations. In news anticipating the 2024 iteration (March 25-April 7), it looks like its 300-plus planned performances will give us plenty of reason to dream.

Passini’s work with the festival began years ago, when she approached people directly as they waited in line to buy tickets. That kind of outreach sensibility is pervasive in Brazil: Theatre spaces that occupy malls or universities make use of existing relationships with their communities. As technology has developed, the commercial center Shopping da Gávea has even added visible kiosks throughout the public space for easy theatre ticket purchases.

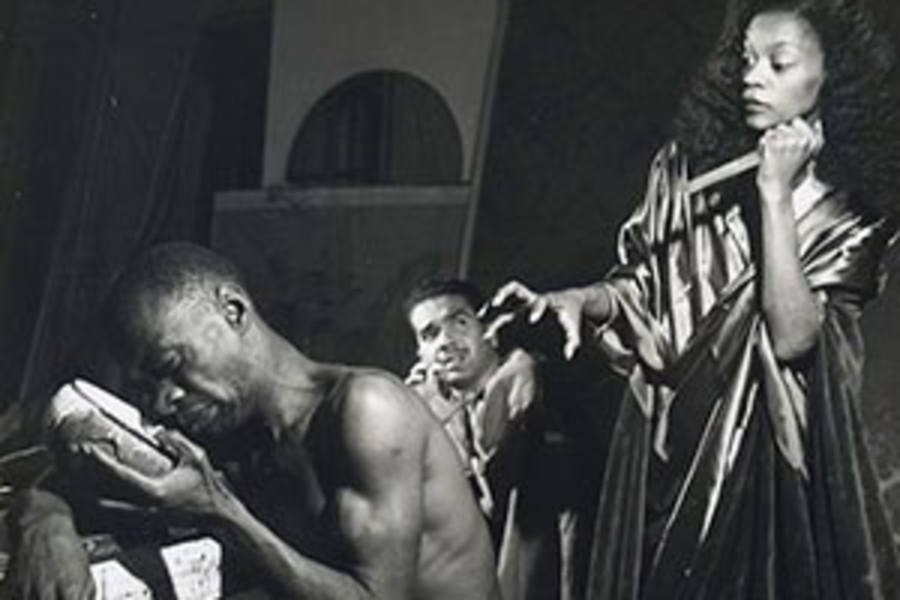

Despite these admirable outreach efforts, theatre in Brazil hasn’t always been as openly liberal or accessible to everyone as we might hope. Political oppression has routinely complicated and harmed the culture, though theatre artists have often defied these trends. During the military dictatorship that presided from the 1960s through the ’80s, companies like Teatro Oficina took tremendous risks in challenging government censorship. The company’s founder, Zé Celso, was tortured for years for his work and exiled in 1974, but fought tirelessly to keep its doors open amid political attacks. In the 21st century, Brazil may no longer be under such a regime, but artists are still recovering from the legacy of ex-president Bolsonaro, whose right-wing administration particularly targeted the queer, Black, and Indigenous communities. Curator and communications expert Pedro Neves explained this insidious climate of repression, having experienced it as a consultant for major performing arts groups.

“It was an implicit censorship,” Neves said. “If a company hosted a project with any political connotation and talked about a minority group’s experiences, diversity, human rights, race, or queerness, these projects were never approved [for sponsorship], and the projects that had been approved, they delayed again and again,” Neves said. “We had a show approved that already had access to funds and was going to premiere—but the venue belonged to a public bank. The people in charge started alleging that the space needed to undergo refurbishment.” In other words, he concluded, “The censorship changed face. We had to learn to live with that.”

What Neves means by “approval” is that, through a law called Lei Rouanet, Brazil’s arts groups can seek sponsorship from large corporations, but to do so they need to be approved by nation’s Ministry of Culture. The exchange involves the performance group giving the sponsoring company a certain number of free tickets and distributing free tickets to young people in schools. To incentivize their contribution, the large companies are given a tax break. Under ideal circumstances, this has enabled the arts to flourish in the country. During Bolsonaro’s presidency, though, fewer projects were approved. Today the arts scene is rebuilding with the benefits of Lei Rouanet, as well as pandemic recovery laws Lei Aldir Blanc and Lei Paulo Gustavo, which give a tremendous emergency cultural funding on a regional basis. Under Lula’s current administration, more projects have been approved and fulfilled, the maximum amount of funds possible for any given project to raise from its partners has risen, and legal adjustments are emerging to better support a diverse array of cultural programming.

The past few years in Brazilian culture have been marked by a complicated convergence of politics, injustice, the pandemic, and anti-Black and anti-trans prejudices, among other issues. As International Theatre Institute president Jeff Fagundes put it, “One aspect cannot be separated from the other.” His memory reverberates with the devastating lasting impact of recent political decisions like Bolsonaro’s failure to accept vaccines for the country and the legacy of colonization in each Brazilian metropolis. Fagundes highlighted the Movimento Negro, the Brazilian equivalent of Black Lives Matter. Forged in the pain and resilience of Black and brown people, regional activism fights to reimagine life and art, from bringing vivid calls for intersectional liberation front and center at Carnaval to advocating for space to live and create without fear. Fagundes’s own practice finds instruction in the lineage of Afro-Brazilian theatres such as the Teatro Experimental do Negro. He brings together ancestry and futurism in his commitment to the next generation, which comes from a personal place. “I wish I had an organization embracing me when I left home as a young person to pursue arts,” he said.

A founder of the Emerging Arts and Professionals Network (NEAP in English), Fagundes linked this organization with ITI to idealize “NEAP Fest,” a week-long gathering of workshops/laboratories, panel discussions, performances, and recognition of local and global practitioners, which last took place Nov. 7-14, 2023, in Rio de Janeiro. Hailing from Brazil, Angola, Zimbabwe, Senegal, Guam, the U.S., Cuba, Chile, the Phillipines, and Slovenia, creatives and thinkers engaged with themes like Ancestral Globalization, Dramaturgies of Conflict, Narration of Indigenous Storytelling, Afrofuturist Theatre, and Area of Risk: The Elitization of Art.

Staff members from Theatre Communications Group, the publisher of this magazine, were on hand as both contributors and attendees for this transcendent week: director of grantmaking programs Emilya Cachapero, assistant director of grantmaking programs Raksak “Big” Kongseng, and outgoing executive director Teresa Eyring. Having maintained a close relationship with Jeff Fagundes over the years, they marveled at his curation. Kongseng particularly appreciated that the Brazilian approaches felt “refreshing,” explaining, “We see it’s on not just a professional but personal level; they care about one another. We have that in the U.S., but maybe what we need is more of that.”

Cachapero cited A Jornada de um Herói, an extraordinary solo performance by Mateus Amorim, which included both physical storytelling accessible to the international audience and local references drawing in the Brazilian audience. A show that left a strong impression was the opening, a cathartic beacon for trans and gender non-conforming representation: Pelada, a Hora da Gaymada. A comedy with music, Pelada centers the dispute over a sports field between a traditional soccer team and a “gaymada” team (a queer Brazilian reclamation of dodgeball). This kind of representation at a government-sponsored event hopefully marks the beginning of a new, censorship-free era for Brazilian storytelling.

Through speed-dating conversations and mixers, the TCG group left with not only surprising takeaways about the nature of theatre in Brazil, but lifelong contacts and tabs on companies from all over. Fagundes said that his plan wasn’t to host a theatre festival wherein people would see a show and go; his aim was to promote meaningful theatrical cultural exchange among people of various nations. In connecting across language barriers, Fagundes reasoned, the gathered leaders in attendance might share more nuanced international perspectives, creative ideas, and new friends and collaborators. This, he promised, is only the beginning.

Outside these expansive festivals and political theatre, Brazil is also home to a thriving musical theatre and comedy scene, both of which have benefited from government sponsorship and support. When it comes to enticing the public in these sometimes more commercial arenas, telenovela names and movie titles still draw the biggest crowds. Movie and TV star Mônica Martelli is currently touring with the highly successful comedy Minha Vida em Marte. At Shopping da Gávea, a mall with theatres, a combination of community buzz and big names turn out the biggest crowds. Seeing Duetos with telenovela and movie actors Patricya Travassos and Eduardo Moscovis confirmed this widely held observation. Amid sold-out runs, my conversations with audience members and other Cariocas (residents of Rio) elucidated how folks are craving more opportunities to go “kkkkk.”

But who gets to laugh? I wonder. As Pedro Neves admitted to me, theatre is still primarily considered an elite activity. While it’s true that audiences are more numerous today than during pre-pandemic times, the consensus remains that there’s much revolutionary work to be done. I continue worrying in day-to-day conversations with family and friends, who warn me that pursuing a sustainable arts career in Brazil remains risky. This sadly prevalent belief reaffirms how key it is for nations to fight for their cultural organizations and for heritage-based forms of creation. As each country honors the importance of its own art-making beyond the obvious American imports that come to mind, we actively fight a cultural colonization whereby our most pressing, linguistically specific, and community-based theatres die (this is just as true of smaller theatres in the U.S.).

In my moments of concern for the Brazilian and global creative ecosystem, I close my eyes to picture the Festival de Curitiba’s Mundanda Refugi orchestra, a musical and human tapestry of our world, filling the air in the streets of Curitiba. I picture the people’s steps slowing, stopping, as the miracle of music disrupts the wear of a long walk home. As Passini recalled, she told her colleagues, “This needs to be on the street; more people will have access.” The result: “It was sensational. People were shocked.”

Emilya Cachapero’s words echo in my mind: It’s all about a “focus on the community connection. Broadway is not the only way to work.” If an orchestra can rejoice and heal on land layered with postcolonial and political traumas, one must trust that Brazil can keep innovating internationally resonant visions for a collective creative future. I hope the houses stay full—que as plateias fiquem cheias—with people, expansive diversity, belonging, access, loud laughter, and hope.

“O futuro é ancestral e a humanidade precisa aprender com ele a pisar suavemente na terra.”

“The future is ancestral, and humanity must learn with it to walk gently on the Earth.” -Ailton Krenak

Gabriela Furtado Coutinho (she/her) is the associate Chicago editor for American Theatre. gcoutinho@tcg.org