In the bygone heyday of dinner theatres, one draw was the chance to see both new talents and fading stars in an intimate, affordable experience. Some lucky Omaha audiences in the late 1970s and early ’80s got the chance to witness the twilight of a theatre god when Dick Mueller, founding leader at the Omaha Firehouse Dinner Theatre, got the legendary Joshua Logan to direct shows there not just once but four times.

Mueller, an Omaha native, came “to theatre through the backdoor of nightclubs,” starting out in an all-male vocal group, then acting in summer stock, studying in New York, and honing his chops in Midwest theatres. Entrepreneurially minded, he started the Firehouse Dinner Theatre, an Equity house, in 1972, and business boomed.

Landing Logan, best known for co-writing and directing such Broadway and Hollywood titles as Mister Roberts and South Pacific, was a something of coup. In a recent interview, Mueller called Logan, who helmed a total of 29 Broadway shows and 11 films, “the Hal Prince of his day,” during the so-called Golden Age of Broadway.

By the 1970s, though, Logan’s aesthetic seemed passé to tastemakers in the age of Fosse and Sondheim. (He also struggled with bipolar disorder.) His last Broadway credits came in 1979, as producer of Larry Cohen’s Trick, and 1980, as director or Horowitz and Mrs. Washington. Neither fared well. So Logan increasingly went to where he felt valued, teaching at Florida Atlantic University and directing at the Firehouse.

Mueller said he never got the sense that Logan was slumming or stuck in the past. Instead, he thinks Logan saw working at the Firehouse, far removed from the national spotlight, not as a comedown but as a chance to keep his craft sharp. Logan’s Broadway aspirations never died, as he campaigned for a revival of a 1916 farce called Nothing But the Truth, inviting New York influencers and investors to see its Firehouse mounting in Omaha. He was also developing a Broadway-bound musical adaptation of Huckleberry Finn, before a similar project, Big River, beat him to the punch.

It was the Firehouse’s reputation as a home for new work that drew Logan, Mueller recalled.

“Word got around about this little place in Omaha willing to do original material,” said Mueller. “It was unusual for a dinner theatre to do world premiere productions of original material. In 1975 alone, we produced two world premiere productions of Leland Ball shows, Red Dawg and Battle Hymn.”

An agent was the initial matchmaker. When Mueller heard that Logan was reworking Cherry, a musical adaptation of one his great directing triumphs, Bus Stop, he traveled to the South to see a workshop Logan was directing with a summer theatre group. It was not love at first sight.

“I wasn’t blown away,” Mueller said. When Logan asked him afterward what he thought, he recalled, “I hemmed and hawed. Sensing my reticence, he put his hand on my knee and said, ‘Dick, don’t ever do a play unless you’re in love with it.’ He let me off the hook so gracefully.”

So Cherry didn’t light up the Firehouse, but a few years later, in 1978, Logan came to direct Nothing But the Truth, which he was briefly attached to revive on Broadway (though that production never happened). “It was great and a huge success” at the Firehouse, Mueller said, and it led to “10 years of a beautiful relationship.”

There was one memorable bump at the start. At a press conference with Logan at Omaha’s gilded downtown Brandeis Department Store, where Logan’s memoir Movie Stars, Real People, and Me was being promoted, the first question came from a reporter who bluntly asked, “Mr. Logan, how come you’re in Omaha—are you all washed up in New York?” After a collective gasp and an awkward silence, Logan held his poise and signed copies of the book.

“I was so embarrassed and taken aback that that insult fell on my watch,” Mueller said. “That said more about that reporter than it did about Josh Logan. But he was a Southern gentleman, capable of handling the moment.”

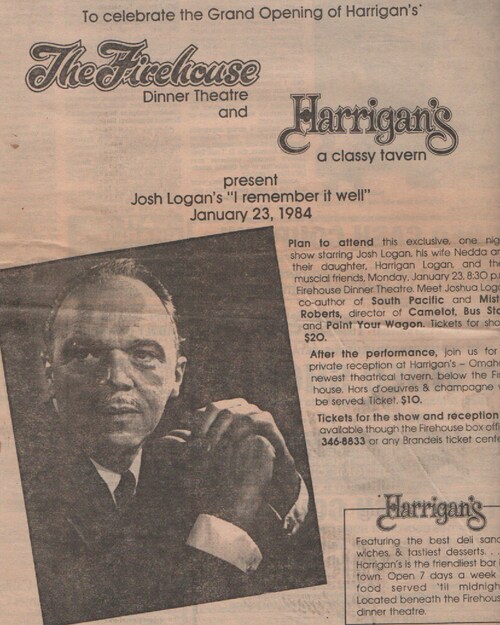

With the success of Nothing But the Truth and their friendship cemented, Logan returned to direct Charley’s Aunt, the comedy that had helped make his name on Broadway in 1940. That was followed by An Evening with Josh Logan in 1982, and a retooling of the same show called I Remember It Well, in 1984. For this personal revue of reminiscences, anecdotes, and milestones, Logan was joined onstage by his wife, Nedda, and their daughter, Harrigan, both of whom were performers.

“They brought their own piano player and used our set for They’re Playing Our Song,” said Mueller, who convinced Nebraska Educational Television (now Nebraska Public Media) to document the show. He said he lent his only copy of the tape to the New York Theatre Guild when that organization staged a memorial service for Logan, who died in 1988 at age 79. After protracted negotiations for the video’s return from the New York Public Library, in whose Logan collection it ended up, Mueller managed to reacquire it.

“It’s a valuable artifact of Josh recounting his own life and career,” said Mueller. “The beautiful set looks fantastic in the video. Josh owned the audience.”

(Call it coincidence or synchronicity, but the man who produced the video, Marshall Jamison, was in the original Broadway cast of Mister Roberts and assistant-directed Picnic, both under Logan’s direction.)

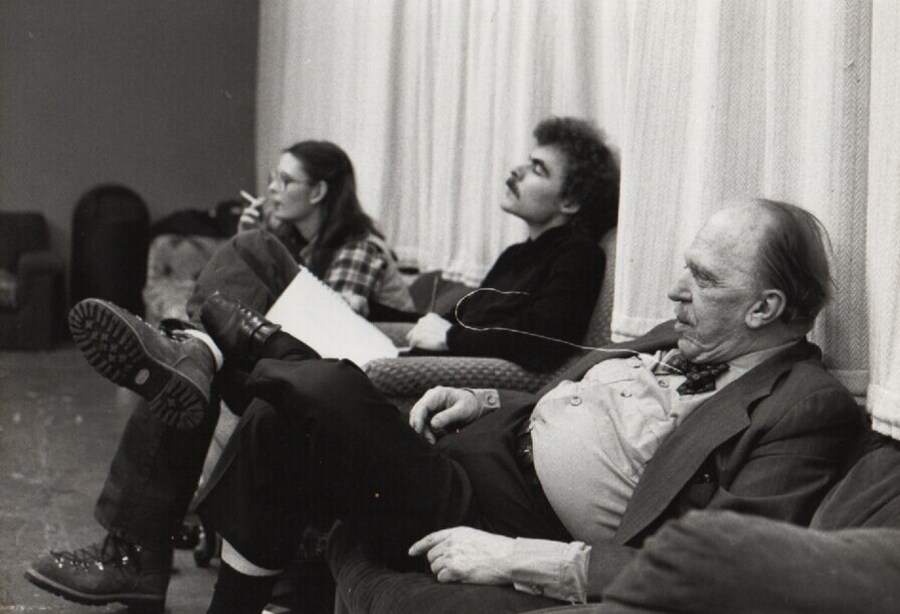

What was it like to work with this Broadway legend? Far from intimidating, Mueller said that Logan “was just an old shoe that loved working in the theatre—he was everybody’s favorite grandfather. He would doze off in rehearsals sometimes, but what he came up with was always brilliant and everything he touched turned to gold, so who cared? He was beautiful to work with. He loved working here, and wrote a lovely open letter to Omaha we displayed in the lobby.”

The dapper Logan directed wearing a sport coat and bow tie, and charmed players and patrons alike. He struck up an instant rapport with Omaha stage legend Rudyard Norton, a friend and colleague of Henry Fonda’s. Only once did Mueller glimpse another side of the famous director.

“In dress rehearsals I thought he was unnecessarily hard on the pianist, whom he nearly brought to tears,” Mueller said. “That’s the only time I saw even a smidgen of him being difficult. He was a sweetheart.”

Logan’s wife, Nedda, was his companion and champion. “They were great together,” Mueller said. Her father, Ed Harrigan, was a stage impresario who’d been the inspiration for the George M. Cohan tune “Harrigan.”

This close working relationship inspired Logan to propose a dream Firehouse project.

“He suggested doing Paul Osborn’s On Borrowed Time, which he had done on Broadway,” Mueller said. “He wanted to play Gramps, with my son Adam playing the little boy. And for the devil part, he said, ‘Maybe I can get Hank and Jim to come and alternate in the role,’” referring to no less than Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart. To Mueller’s regret, he demurred on Logan’s offer, in part, he said, because he was “concerned about him being able to do, much less survive, eight shows a week. Looking back, even if he had died onstage, what a great way to go—doing exactly what he wanted to do.”

When Logan did at last die, in 1988, it was, serendipitously, around the same time as Mueller’s own father passed.

“I was in a run of Music Man when my father died, and the day he died I went on with the show,” Mueller said. “I remember standing at the bar afterward, saying, ‘Wow, what a day this has been,’ when somebody said, ‘Josh Logan died today.’ Not a good day.”

Still, Mueller said, “I’m proud to say we were good friends. What a talent. What a life well-lived. It was a privilege knowing and working with him.”

Leo Adam Biga (he/him) is an Omaha-based freelance writer and the author of the 2016 book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film.