Playwright Tina Howe (Painting Churches, Coastal Disturbances, The Art of Dining) died on Aug. 28. She was 85. Howe’s last play Where Women Go is currently playing at HERE Arts Center through Feb. 25. The following tribute was originally published in Contemporary Theatre Review Volume 34, No.1 (2024). Two previous AT tributes to her memory are here and here, and three of her own pieces can be found here.

At first glance, Tina Howe was the very embodiment of WASPy reserve and decorum. Tall and thin, she sported the same bobbed blond haircut for decades, and it framed a sculptural face that suggested careful observation and an economy of expression in keeping with her Boston Brahmin roots.

But to see Tina this way was to miss the trees for the forest. Look at her feet, where you would see she was walking around in bright purple cowboy boots. Or you could check out her wrists and try to count the seemingly endless number of bangles and bracelets clinking and clacking all the way up her arm as she gesticulated exuberantly while describing a particularly transcendent moment in someone else’s play. If you asked her where she got them, she might answer, “Oh, I wish I knew—they just flew onto my arm one day when I was lost on a side street and had nearly given up hope.”

Or you could watch her look of eager anticipation, as she suddenly produced a giant bejeweled satchel out of nowhere, reached deep inside it, and pulled out a perfectly wrapped gift she had been saving for you. It might be as simple as a mug with a weird shape or a particularly clever saying printed on it, a beautiful journal, or a framed photograph or piece of ephemera from a past production. But it would resonate with absolute care and attention to who you were, and how she valued you, no matter how simple the gift. Careful observation indeed.

There was a not-so-contained muchness to Tina Howe. She had been raised with Protestant privilege and restraint, but could suppress neither her outsized enthusiasms, nor her natural impulse to push against propriety and what was expected of a woman like her. There was an exuberance to Tina that was sometimes mistaken for naïveté or worse, daffiness. It made some gatekeepers, male artistic directors in particular (though not exclusively), treat her with condescension or dismiss her as unserious. Tina’s personal buoyancy was, like that of many of her characters, both innate and fueled by the pressures life and artistry threw in her path.

There was nothing unserious about Tina Howe or her work. Despite the relative privilege of her Upper East Side youth, Tina’s life was peppered with challenges, and she was certainly well aware that her own aesthetics and point of view left her out of step with many of her contemporaries. She made her first inroads into the professional theatre in the early/mid-1970s, when the prevailing realistic aesthetic Off-Broadway was defined by the gritty dissections of American masculinity associated with David Mamet, David Rabe, and Michael Weller. Even the realm of formal experimentation was especially associated with men like Richard Foreman and Sam Shepard. Tina’s work centered on characters who struggled to function and build lives in a rapidly changing and increasingly disconnected world. It dared to innovate in form and content at the same time; on the one hand focusing its attention on complex, neurotic women as protagonists, and on the other, blowing up the conventions of psychological realism to reveal deeper truths about human desperation.

And they were, perhaps most radically, essentially comedies. Her uniquely outrageous approach to theatricalizing flawed characters in crisis, and her signature flights of language, also positioned her adjacent to but somewhat out of line tonally and politically with the more explicitly “serious” feminist work of the period, such as the plays of María Irene Fornés, Caryl Churchill, and Ntozake Shange.

One of the most indelible moments of Tina’s storied career was the opportunity she had in 1986 to introduce her “idol” Eugene Ionesco before a speech he gave in a rare visit to New York at the 92nd Street Y. There is a photo she cherished of the two of them, in which she proudly proclaimed that she had grown a third arm to have an extra one to wrap around him (it’s a black and white photo that does indeed look like Tina has three arms). She felt that it was the height of perfection to have such an off-kilter photo with him. She shared her personal history with Ionesco’s work, describing the revelatory moment when, as a young woman and recent graduate of Sarah Lawrence College in 1960, she wandered into the tiny Théâtre de la Huchette during a year spent in Paris to see The Bald Soprano (which has been playing there continuously since 1957). “It was as if I had been struck by lightning,” Howe recalled. “The curtain went up and all hell broke loose. I had not seen such goings on since the Marx Brothers movies. The sheer outrageousness of Ionesco’s dramatic sense and language, the way he turns things on their head…He is often called an absurdist. To me, he is the ultimate realist. He shows us the laxness of reality and what a pathetic time we have getting through the day. For me it is the kitchen-sink dramas and formula comedies that are absurd because they present us with stereotypes and not the real world.”

This perfectly encapsulates the influence Ionesco had on Tina as a writer, but it speaks to a sensibility and world view that were already waiting to be expressed. She didn’t emulate or copy Ionesco in her work. Ionesco liberated something in Tina, and allowed her to reveal herself with abandon and molecular comic precision. The label “absurdist” dogged her as well. She bristled at her work being described that way, precisely because the bold theatrical language and the intense, heightened desperation of her characters were by no means imposed affectations. They were the purest expression of how Tina saw the world and how she could write people, women especially, “in extremis,” as she often said, with piercing insight and compassionate humor.

The anecdote about her encounter with Ionesco’s work was one she often shared with me, not least when we were working on her own translations of The Bald Soprano and The Lesson, a project imagined with my mentor and then boss Robyn Goodman (who had acted in Tina’s Museum Off-Broadway at the Public Theater in 1978 and produced her work several times after co-founding Second Stage with Carole Rothman) and commissioned at Manhattan Theatre Club. Robyn and I had stumbled into a conversation about Ionesco with Tina—we had been looking for a project for the seminal avant-garde director Joseph Chaikin, who was then suffering from aphasia, and Ionesco’s plays came to mind, not least because they are populated with characters who are defined by their struggle to communicate. Tina seemed like a perfect match for the plays to us before we even knew the totality of her obsession with Ionesco. She leapt at the chance to do the translations (getting the rights from the Ionesco estate was another matter) but also immediately internalized the weight of the task. How to do them justice, and enliven the plays past the limits of prior English versions without veering from the specificity and searing luminosity of Ionesco’s French? Particularly with the violent and very dark The Lesson, she felt the weight of responsibility of amplifying the legacy of her theatrical and literary hero.

I was fortunate that MTC did not finally opt to produce the translations, so I was able to take them and Tina with me to the Atlantic Theater Company when I assumed a new leadership position there. They were produced there in 2004. The translations fizz with the kinetic energy and rhythm of precise, juicy language. Abundantly speakable by actors, they capture the pain and desperation beneath the comic surface of Ionesco’s voice, sneaking up on the audience, swinging them in an instant to horror from rolling laughter. Tina felt such a debt to Ionesco that I think the process of working on these plays was simultaneously joyful, stressful, and liberating. She wanted to add to his legacy with the project, not her own. And it was in that spirit of curiosity and generosity that she succeeded.

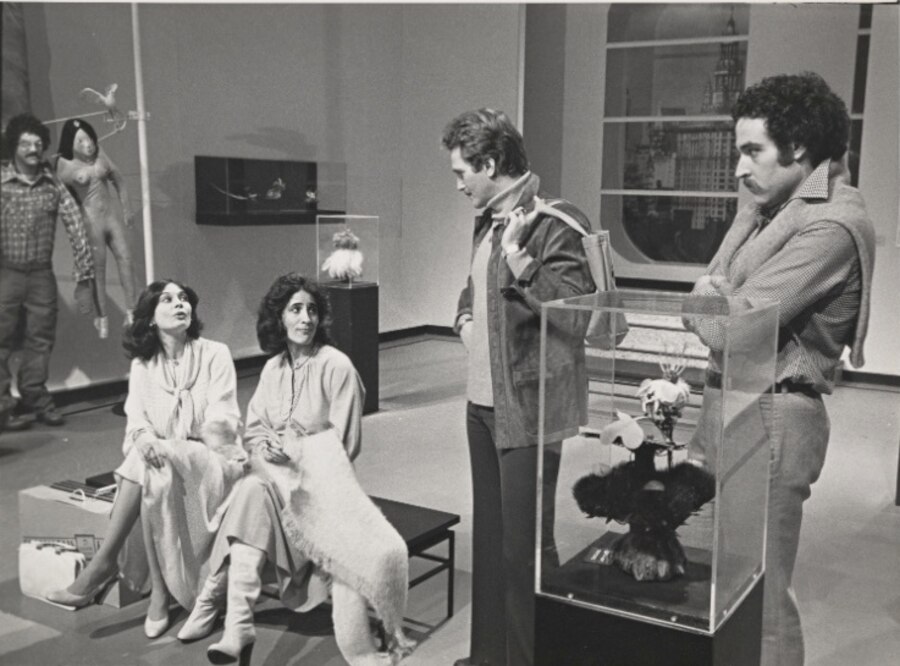

I suppose that I feel a similar impulse relative to Tina’s legacy. I first encountered her work in high school, when an enterprising fellow student (now a playwright and screenwriter, mentored by Tina) decided to mount her abundantly populated play Museum, and I was cast in it. Incidentally, I had only very recently seen a student production of The Bald Soprano, and it had likewise blown my mind. No doubt it didn’t hold a candle to the Théâtre de la Huchette production, but the play came through nonetheless and was like nothing I’d seen before.

My early exposure to Tina’s writing isn’t worthy of an essay, except that in retrospect it mirrors, more modestly, Tina’s own lightbulb moment with Ionesco’s work in Paris. To me, Tina’s plays find their emotional power and humor in the elegant balance of propriety and naked outrage. The roiling strain of suppressing an outburst of emotion or an angry impulse fuels dramatic tension, and reveals characters who long for triumph over their deepest fears and release from the torture of personal and linguistic restraint. They fail over and over again before finally finding some grace or ease, but never are they sacrificed by their author at the altar of satire or ridicule. Tina wrote characters who struggled mightily, and behaved outlandishly under duress, but she wrote them all with a kind of ruthless compassion that grabbed my attention and my sense of humor from the start.

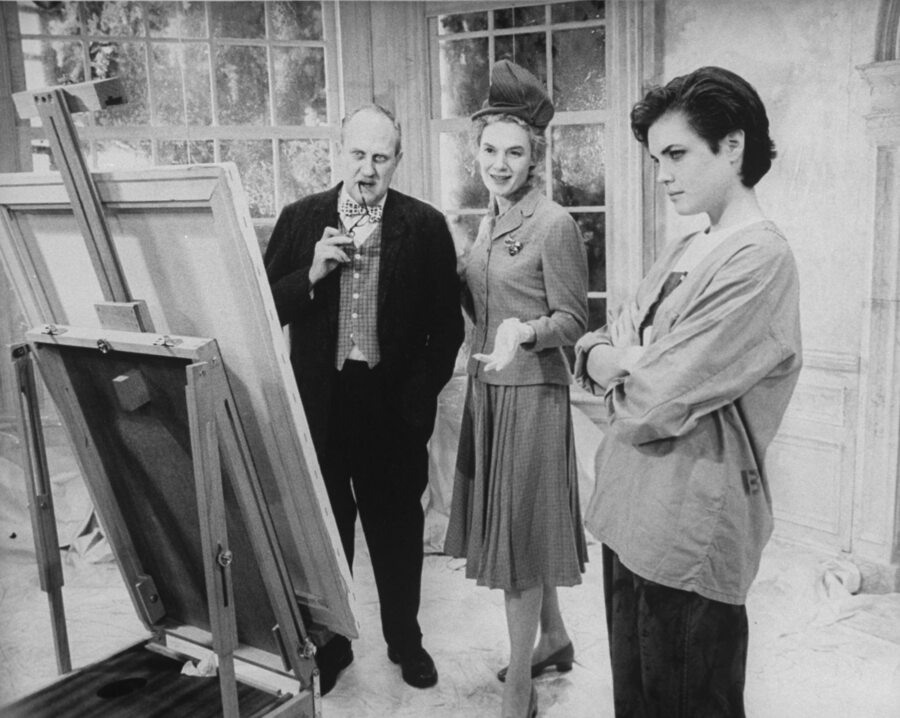

It was this stylistic unruliness that made some critics and artistic directors dismiss her early work, including Museum and The Art of Dining (in which Kathy Bates famously had to douse Dianne Wiest with water when she actually caught on fire during a performance), and Tina’s first play, The Nest, which had closed upon opening in 1970. Tired of swimming against the tide, she deliberately turned her attention to writing what she described to me as “more polite, decorous” plays, partly in hopes of being more widely produced. Those two plays, Painting Churches (1982) and Coastal Disturbances (1986), both transferred commercially, and the latter made her a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and a Tony nominee. The former play centered on the simple action of a young New York painter returning home to Boston to help her aging and eccentric parents pack up their long-time home, nonetheless lifts theatrically, with flights of language and the darker undercurrents of unspoken family tensions. It is as if Tina could not resist the temptation to take a familiar and otherwise dusty scenario and wake it up with characters who cannot hold back their own impulses to break convention, and who come together through sideways and cock-eyed revelations of shared truth.

With the added constraints of a staid setting and buttoned-up characters, in other words, Tina’s anarchic streak shone through even more poignantly than in some of her more overtly wild earlier plays. Likewise, in Coastal Disturbances, Howe gives a middle-aged meditation on romance and missed connections cosmic, or rather climatic, scope by setting it on a Massachusetts beach and subjecting all of her characters to the mercurial and forceful whims of the weather, which becomes its own character, really. The playwright’s voice, even in her deliberate attempts to circumvent the slings and arrows of her critics and doubters, was irrepressible, and arguably the secret to the plays’ popular success. Perhaps unsurprisingly, her next plays, notably Approaching Zanzibar (1989) and One Shoe Off (1993), were a return to her looser, more heightened style.

I was lucky enough to convince Tina that we should revisit her raw, layered 1973 play Birth and After Birth at the Atlantic Theater Company in 2006. Examining two couples’ conflicting feelings about child-rearing and fertility, the play’s action is punctuated and given wild comic urgency by the presence of Nicky, a rambunctious, unfiltered 4-year-old meant to be played by a large adult man. Like many of the casualties of Tina’s early career, the play had never had a major New York production, even as she had gone on to develop a reputation as a major playwright. Tina felt that because the play dealt so frankly with women’s ambivalence about child-rearing (Nicky’s mother, Sandy, is enormously stressed out planning his birthday party, and actual sand pours constantly from her hair) and presented a chaotic and unsettling view of both the “traditional” couple and the childless friends who come to visit, that it was dismissed by men and women alike at the time of its writing for being somehow “out of step.” Once convinced, though, Tina dove into rehearsals as if it were her most recent work; I was stunned at how easily she was able to jump back into it, well over 30 years after it was written, to find new moments to finesse and ways to flesh out characters she said she “always felt she’d given short shrift.”

We were fortunate that my colleague Neil Pepe, the artistic director of the Atlantic, shared my view that the play was timely in its excavation of themes of marriage, child-rearing, sexuality, and competition between friends in a surprising, antic framework. In the context of the production history at the Atlantic (founded in part by Mamet), Birth and After Birth represented a certain kind of aesthetic departure. The theatrical coup-de-grâce of the play is when Mia, an anthropologist, recounts her observation of the birth ritual of a humanoid tribe she has discovered that involves reinsertion of the newborn into the mother over and over again after birth. It’s both shocking and hilarious, and brings Mia to a state of both ecstasy and profound grief. In staging it, we followed the cues of Tina’s language to transform the space into an actual jungle, both to align the audience fully with Mia’s disturbing transcendent experience, and to allow the play to lift, as Tina intended, into the realm of truly broken (and then restored) reality.

It was some of the scariest and most challenging work I have done as a director, and I had to get comfortable with the fact that if we did the play “right,” audiences would be divided. Tina Howe unleashed was not for everyone—her vivid use of imagery and language, coupled with a sometimes frantic pace and an impulse to stage just-barely-controlled chaos, was in fact too much for some. But she was driving at the heart of the human need for connection, daring to show us what happens when subtext becomes text, and people at wits end begin to unravel in front of us.

My relationship to Tina’s plays came full circle when I acted in a revival of Museum for New York’s Keen Company in 2002, and directed two glorious one-acts of hers, Through A Glass Darkly, and Caution: This Bus Kneels, Stand Clear (for Atlantic’s 20th and 25th anniversary seasons, respecitvely). Not to mention the innumerable conversations over dinners and “giant cocktails,” as she loved to say, where she would discuss whatever she was working on next.

Shortly after she passed, another friend of Tina’s said to me that it was particularly sad that Tina was often admired but rarely celebrated. She spent a lot of time cheering the work of others, especially playwright protégés Sarah Ruhl, Lindsey Ferrentino, Victoria Stewart, Chisa Hutchinson, Andy Bragen, and her contemporary Chuck Mee, among many others. She certainly deserved the same in return. Getting to know Tina, learn from her, and to feel her investment in me was transformational. Her work had stoked my imagination before I knew her, but not only was Tina more than I imagined in every respect; she took me in hand and challenged and enabled me to risk fully expressing my own creativity and outrageous spirit by entrusting me with her words.

One of my favorite plays of Tina’s is among her least known. Titled Disorderly Conduct (2002), it was performed as the closing piece of an evening of plays at New York’s Town Hall that were written in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. In it, dozens of New Yorkers of every background and identity slowly fill the stage, only to interrupt the hustle of their day and turn their attention to the sky. We realize, gradually, that we are in 1974, and that a cross section of this most diverse city is standing together in fear and awe as they watch Phillippe Petit make his way across a tight rope between the Twin Towers. The play ends in silence, everyone looking up, just taking it all in, seeing the world completely differently, maybe for the first time.

This is exactly what Tina’s work did: It made us look at the world and ourselves anew.

Christian Parker is a dramaturg, director, and professor of professional practice at the Columbia University School of the Arts, where he oversees the MFA dramaturgy concentration. He began his career at Manhattan Theatre Club, spent many years at the Atlantic Theater Company, and has freelanced around the country.