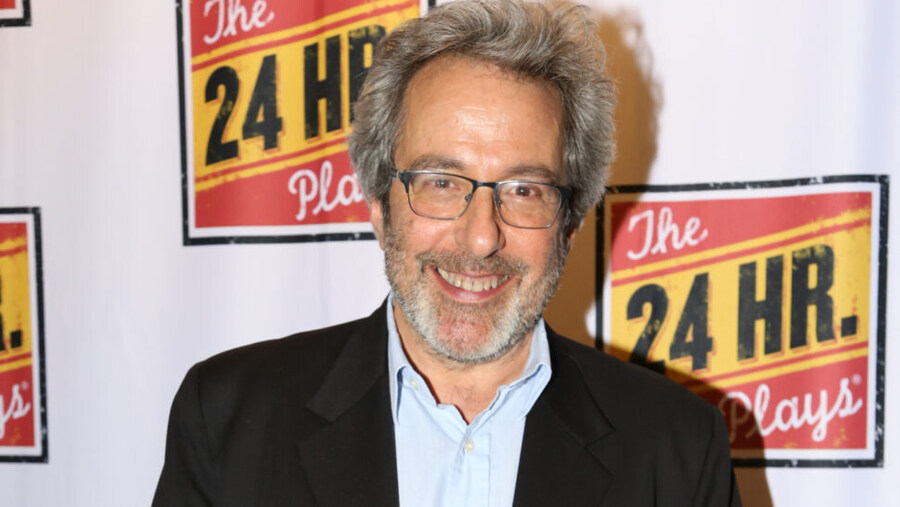

On Oct. 23, The 24 Hour Plays on Broadway produced their annual gala, featuring six brand new one-act plays, written the night before, at Town Hall. I’ve been writing for The 24 Hour Plays off and on since they started their Broadway tradition on Sept. 24, 2001 (The 24 Hour Plays were created in 1995). So on this night they were honoring me, and after intermission I gave a speech.

I was waiting backstage, about to go on, when Mariska Hargitay, just off a plane, rushed in to give me a hug (we’d worked together for eight years on Law & Order SVU). Seconds later I was introduced, so I asked her to come out onstage with me. My speech was folded up, there were 1,000 people in the house, and I was nervous. The speech went something like this…

(Walks onstage with Mariska Hargitay, gestures to her.)

WARREN: I brought back-up.

(Mariska hugs Warren and moves to the back of the stage.)

Well, thanks. This is really lovely, and really embarrassing, and really lovely. In honor of The 24 Hour Plays, I got up at 6 a.m. and wrote this in about an hour. And that’s true. Then I went back to sleep and tried to tighten it up later in the day. And then on the way here, I got out of the subway, I’m on 42nd Street, and I do this:

(Takes a step, feigns accidentally dropping his script, and walks away.)

And the way life works, somebody notices, a stranger, and says, “Hey, buddy, you dropped your paper.” Had he not said something…that would have been just…great. And that’s the journey of this script to this stage. Now I gotta take these off—

(Takes off his glasses, looks out to audience.)

It’s nice to have so many friends here from so many different parts of my life. This is so much better than a memorial. It makes me nervous. Does this mean I don’t get to write again for the project? It’s just like—

(Mimes being “swept to the curb.”)

But anyway, there’s all these people here tonight—onstage or in the audience—who saved or shaped my career. Mark Linn-Baker, Kenny Lonergan, Pippin Parker. Gina Gershon and Nadia Dajani did my one-acts, which were like four dollars to get into like a hundred years ago. We did them at Naked Angels and we did them in the basement of the West Bank Café, and we did them at holes-in-the-walls, theatres that were going to be torn down the next week. It was how we broke in. Those friends from early days have always been staunch. Actually, almost everyone who did one of those one-acts eventually appeared as a pedophile on SVU. It’s my way of giving back.

Christian Slater is here in that nice mullet wig he wore in his one-act. He played me in Side Man and he kept the show running on Broadway and that changed my life. Fuck, I know I’m going to cry up here.

(Takes a breath.)

Katie Erbe’s here. She helped me survive my first TV show with some very complicated personalities. She was not one of them. And then later tonight you’ll see Raúl Esparza, Jamie Gray Hyder, Octavio Pisano, Allison Pill, Ari’el Stachel, dozens of other people who’ve been on SVU or In Treatment or Lights Out. They’re all here tonight. And if you’re wondering about that mix—SVU, In Treatment, and a boxing show—it’s because I can’t pitch a script to save my life. I just take the jobs. That’s what I’ve always done.

That you all in the audience are here means not just a lot to me, but to everybody who spent the last day running on this mix of caffeine, talent, fear, adrenaline, panic, panic, panic. One other thing that’s part of tonight…because of the ongoing strike, which is now 100-plus days for SAG-AFTRA and really began with us, the WGA, on May 2nd, coupled with all the cutbacks in theatre—a lot of the people you’re seeing, a lot of us haven’t had the chance to write or perform in far too long. So—

(Starts to tear up.)

So I’m just happy we’re all out of the house, and people are getting to perform. And that you all showed up, despite all the dark stuff going on seemingly everywhere. The news has been horrible lately. So why not come together and put on a play, or six of them?

They tell me I’ve done 11 of these. I have no memory of about five of them, including apparently my second one that Mariska was in. I don’t know that either of us remember that at all. That was long before I knew that I was going to make 175 episodes of SVU with her. Work that, in some ways, The 24 Hour Plays prepared me for. I’ve learned a lot doing these overnight one-acts, from this—is it even a process? Much of what I learned, I probably should have learned earlier, like as a kid or in Al-Anon or somewhere. But for me, it’s been these 24 hours that taught me.

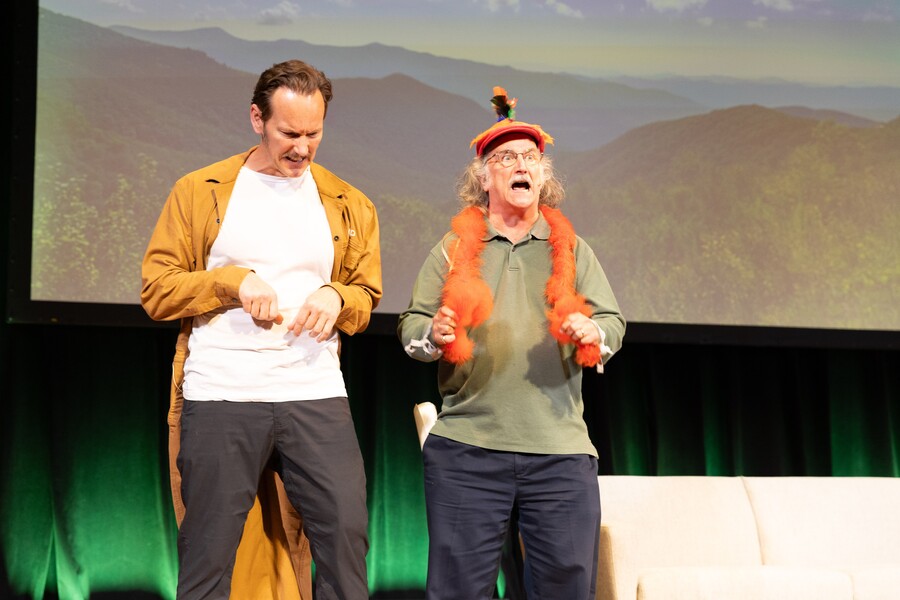

One of the first things I learned here, that you all should know, is: Be open. When the 24-hour process begins at 8 o’clock Sunday night, the actors bring in props: the mullet wig, the teddy bear you saw earlier. The actors then each get up and tell the writers a little about themselves. And if they’re Bebe Neuwirth, they curtsy afterwards, which is just fantastic. One of the things I’ve learned: Listen to your actors. If you come in—some writers, and I’ve seen this, they come in knowing what they’re going to write. They come in with a notion of what they’re going to write and how many actors they’re going to take. And they draft two actors and then they stop. And inevitably when they do that, they fail.

Because you have to be open. You have to. Because after the actors go, finished with their sweet, nervous presentations, the writers and directors draft their cast. It’s like a fantasy draft for playwrights. It’s like, “I’ll take Mariska, I’ll take Mary-Louise Parker, I’ll take”—people who would never do a play of yours ever in real life. But for this night, they show up.

In my first year, 2001, there were 30 actors’ Polaroids on a table, and the writers go around and draft, and a couple of them are like, “I got my two, I’m done.” And there’s like seven people or five people left. I didn’t want anyone to be left out, so I added ’em to my pile. I go to my room, I got these Polaroids and I’m like, “Fuck me. How am I going to get this group of actors to possibly be in a room together?” So I put them in a jury duty hall. Jury duty, the great equalizer. Because I took these extra people I had cast, I ended up doing a one-act about jury duty that I would never otherwise have written. I was in the moment. That’s what this teaches you how to do.

The next thing these 24 hours teach you is: Don’t overthink. The beauty of having to create something overnight is even if, like, say, hypothetically, you procrastinate…you have to come up with something. There are actors waiting, there are people calling you. The people who work here are unbelievably nice, but at 4 in the morning, they start to get nervous because they’re checking on you at 2 and you clearly haven’t started, and they’re back at 4 a.m.—and you do that thing, you’re like, “Oh, it’s almost done.” And they know you’re lying and you know you’re lying. And the clock is ticking.

Let’s say you start at 3 a.m., your subconscious guides you, and if you’re lucky, you have time to do a very quick rewrite before they come in and forcibly take your script away from you. The directors read your piece, and then at 9 a.m. the actors come in and they’re really scared. They’ve got nothing but their instinct and experience and first choices. That’s what they have. For once, no one gets to overthink it. You don’t get to drown in network notes or notes from friends and you don’t have to worry about algorithms, you just have to show up.

Which gets me to: Take care of your actions (and your actors), let go of the results. The 24 Hour Plays remind us: You can’t control your career or the play you’re in or even the scene you’re in. I’ve been here when people go up on their lines—no idea what their line is, or even who or where they are. That kind of “up.” One night, years ago, a famous actor went up on her lines, and Aasif Mandvi, who was in “my” one-act with her, was both prepared and gallant: He pulled a script out of his pocket, handed it to her, and bowed. The show went on.

And it played better because of the screw up. It’s the screw-ups and the rescues that you remember. They’re great. Another night, everybody onstage went up at the same time. And David Lindsay-Abaire, who maybe should look at some of the things on this list, screamed out the line from the back of the house at the top of his lungs. Okay, so maybe writers have some control issues, but, you know: Your work is always going to get away from your intent. That’s another thing you have to learn. Sometimes when that happens, it’s great; sometimes it breaks your heart. But in these 24 hours, as in life, you have to let go. There’s no perfect up here. There’s a lot of very, very good and utterly wonderful, but it’s not going to be exactly what you thought. And that’s always good to remember. Once the curtain’s up, you have to just get out of your way and let the show go on.

My life changed over all these years of doing these plays. I started a family—my wife, Karen, and Isabel and Imogen, my daughters, are here tonight—and they’ve had to put up with me when I come home from the all-nighter, and I’m not this charming. And they’ve had to put up with my pre-show anxiety and tension. All of us need that support when we’re up here. But I’ve always come back whenever I was asked. When I was showrunning SVU or other shows—those are intense jobs. They’re all-consuming. You’re working way more hours a week than you are years old. But no matter how exhausted I was, I’ve jumped at every chance to be here. I loved knowing that at least once a year I had these 24 hours. It’s like leaving the pit of a Broadway show and playing in a jazz club. I just needed it. And sometimes it went really well and sometimes it was a disaster, and either way it was great.

So now I’m being honored, which is weird and strange, and we come together in another horrible time. But that’s always been part of this. The truth is, seemingly bad timing has always been part of this project. Because this project, more or less began with the millennium.* And, to be honest, this millennium has gotten off to a terrible start. Think about it. It’s just been a bad millennium so far. The last time I wrote a 24-hour musical, I Zoomed with the composer and Jessica Hecht, who sang our song in her apartment as a masked director shot it on an iPhone. And it wasn’t…this (gestures to the stage), you know, with lighting, and mics, and costumes. But we were still creating. A few years before that, we all came together right after Trump was elected and everyone was in shock. I think that was the night we got up off the floor and started to fight back.

Which brings me to the first time I did this, the jury duty piece. We gathered less than two weeks after 9/11 at the Minetta Lane Theatre. Downtown. Everyone was numb and we were still tinged with smoke. And then, somehow, 24 hours later, even though a lot of people hadn’t been out of their houses in over a week, somehow the audience just… showed up. I don’t know from where. We created six plays that night, some that tried to help us understand what we were feeling, some that took our minds off of it, some that just got us through the night. But we came together as a community and tried to take care of each other. And here we are again tonight, under dark clouds.

But the community comes together again, panics, creates, laughs. And we root for each other and we come to support each other, and soon you realize everyone is just doing it for the joy of it. The thrill of it. And that reminds us of how we all started out, why we wanted to do this in the first place. Something we too easily forget as we try to make a living, build a career, worry about results.

So thanks to The 24 Hour Plays for everything they’ve given me. I should be honoring you and everybody here tonight. Thank you all for coming. On with the shows.

(Mariska comes back on to give Warren his award, then walks him offstage. The show goes on.)