“You! Me! Right now!”

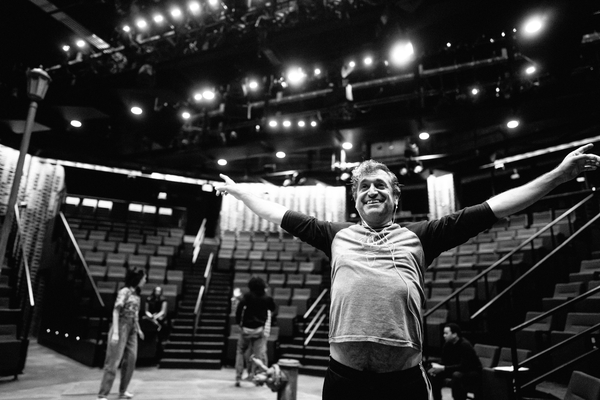

With a camera in one hand and, prophetically, light in the other, a Chicago theatre superhero dives under tables, runs along Writers Theatre’s backstage corridors, and easily climbs Eurydice’s steeply-raked set, all in search of uplifting the scene in front of him. This radically joyful, loving, and attentive photographer, armed with a belt containing three cameras and wearing your typical backstage all-black clothing, is anything but “behind the scenes.” Joe Mazza stands firmly in the action.

Known for event, pre-production, rehearsal, headshot, family, and portrait photography, Mazza has worked with countless productions and artists in Chicago, from Court Theatre to Chicago Shakespeare to Chicago High School for the Arts. In person, Mazza overflows with presence and a natural ability to make connections, reminding those around him that “this, right here, is an exciting moment, a celebration,” as performer and friend Elizabeth Ledo put it. Across his three-decade-plus career, Mazza has developed a distinctive approach, one that centers the humanity of individuals caught in the lens, making him a go-to name for many Chicagoland theatres hoping to capture joy and community during a difficult time in the industry.

“There’s a lot of transition happening right now, and it’s scary,” said Ledo. “There’s still a weight. Sometimes for an opening night or celebration we can pretend, but when we wake up the next morning the anxiety comes back. I think what we can try to embrace is how Joe and I give each other a look in these moments saying, ‘Let’s keep moving.’ He reminds us that even though we’re scared for the industry; live theatre, artistry, expression, and celebration can still be renewing.”

As soon as Mazza enters a room, you feel the positive energy shift. His kindness loosens bodies’ tight anxieties and welcomes them to breathe, to feel welcome. He said he never thought this work would be so psychological. “It is the most delicate process,” he told me. “It’s like going to a confessional.”

Accordingly, he pays careful attention to every person and emphasizes how grateful he is to be in space with everyone. Observing him at work, I marveled at his utter in-the-moment energy.

“Some friend of mine said, ‘Looking at your photos, nobody would know how loud it is when you’re working,’” Mazza said with a smile. “‘Nobody would know how much you move around and how much you scream. It’s just so weird that these photos are so still and quiet.’”

His method retains a balance between preparation and on-the-feet thinking. While he does extensive research, especially before a pre-production shoot, he knows he’ll find incredible artistry in the room through collective intuition. He aims to capture truth and finds himself particularly drawn to movement, essence, blur, music, and vibrant color. As he experiments sharply with lighting, the photos can look otherworldly but still real, with an honest beauty. Longing to see what happens when you “take everything away,” he encourages the raw simplicity of storytelling—nothing too fancy. Looking at his photos, my body viscerally responds to the joy in event images or the pain in his moving pre-production shots.

“The photograph is the vehicle,” he said. “When you read a novel, you’re not thinking of the actual, physical book. Your head is in the story.”

But he’s not working only for those of us who identify as artists: Mazza also enjoys centering people who “don’t think they are creative,” like, say, friends and family attending opening night. Holding sacred the idea that everyone is creative, he loves the journey from confusion to surprise to enthusiasm for people who aren’t used to his process or artistry. He is also attuned to who might need space to build trust; Mazza notices some folks like to watch him in action before he pulls them in. Each shoot, he prays he will be able to truly see everyone and be creative.

“He has this enthusiasm and excitement that supports this work-in-process that can be uncomfortable because you are exposed,” said Ledo. “He makes it celebratory. He somehow figures out the vocabulary and the energy that’s right for each project. But it is still this same guy.”

Mazza has photographed Ledo during both her lows and highs, and through it all she’s noticed the way he takes in every emotion and factors it into the shoot. Her sessions with him have varied from silly and fun to emotional and cathartic.

“He lets us be beautiful, vulnerable, raw all at the same time, and he captures that,” she said. “Any of us who see those pictures want to share them and say, ‘Yes, this is how I look, how I feel, or how I want to look or feel—I want to remind myself of this.’”

Mazza’s ability to connect deeply with those around him dates back to growing up in the Boston area surrounded by art. His mother played opera at home, his Italian dad played in a band, and he himself performed in opera tours as early as age 9. What really generated a lasting spark, though, was going door-to-door with his father when he worked as a salesman. Starting around age 10, he would often have hours-long conversations with people at their doorstep; tagging along with his dad became a kind of excuse to connect with people. Personal background or proximity to his age didn’t matter, Mazza shared, as he heard tales ranging from how folks were doing that day to epic feats like surviving a sinking ship and saving people.

“I learned that people, when you start talking to them, they’re warm, and they want to talk to you,” Mazza said. “I heard so many stories that were just amazing.”

This people-centered approach has stayed with him. Though he’s tried photographing objects, he truly loves his medium for its interactive play and defiance of life’s hardships. In the face of pain that tinges the return to in-person programming, Mazza seizes the blessing of “right here, right now.” When photographing, he said, “I feel we’ve had a moment, and we can all say we’ve been here. We’re alive, we’re happy right now, in this moment—this is something we’re giving each other. Nothing else matters. It’s a real ‘fuck you’ to death. And then you get proof too, because you get photos out of it!”

He recalls loving theatre for such in-the-moment surprises. At 16, he was playing a dad onstage when the set pieces collapsed around him, so he ad-libbed, “They just don’t make houses like they used to!” As a teen, Mazza briefly opened a New England photography business. But in college, he primarily focused on acting, writing, puppetry, and filmmaking. In 2009, he picked up the camera again to shoot a solo performance he’d written, and said, “Instead of working on that, I was eager to go, ‘Come here! I want to do your portrait!’ In 2010 I did a lot of portraiture, and then on April 27, 2011, I said, ‘I’m going to do this only. I’m opening a studio.’”

He remembers the exact date in part because he later learned his father had passed the same night. The company he founded, Brave Lux, in a way honors how his father treated and welcomed people’s stories. “He was very generous with people in public and connected to people,” Mazza recalled. In turn, he hopes to join a web of human kindness and connectedness.

“Everybody is connected,” he said. “Everybody wants to connect, even if they don’t think so at the moment. There’s that everyday thing that pulls us away from each other and makes us feel like we’re alone in some ways. I feel like, with photography, I can come in and say, ‘Nope! You are coming with me!’”

There are fundamental truths, I think, in the cosmology of the human spirit, which Joe Mazza has embodied at every stage of life. There’s a lot of wisdom to be found in the kid who plays, refuses to snap out of living in-the-moment, and listens to hours-long stories at strangers’ doorsteps. There’s a deep knowing in the 16-year-old who makes people laugh even when the set collapses around him. And there’s a particular triumph in the adult who, despite many years on this weary earth, hasn’t lost that glimmer in his eye, and who preserves and spreads the magic with every “click.”

“Right now is always the most vital time to be creating together,” Mazza insisted. “It will be true in 10 years, and it will be true for any artist. But there really is, right now, an urgency to show humanity to one another.” This, he said, is “absolutely vital to survival.”

Gabriela Furtado Coutinho (she/her) is the associate Chicago editor for American Theatre. gcoutinho@tcg.org