Robert Brustein, founder of Yale Repertory Theatre, American Repertory Theatre, and the ART Institute, as well as longtime theatre critic for The New Republic and author of Theatre of Revolt, among other books, died on Oct 29. He was 96.

You could not ignore Bob Brustein. His admonitions were in your face, in your ear, in your mailbox. If you were young and ambitious and desired all the things that the young and ambitious desire—fame, fortune, glittering prizes—Bob was your conscience. To be Bob’s student or colleague or friend (I was all three, and for more than 50 years our lives were intertwined) was to be always held to the strictest moral standard.

Bob overflowed with passion, intellectual rigor, righteous indignation, and unshakeable conviction, a compelling if sometimes daunting mix. We want our mentors to be better than we are—up to a point. His saving grace, to his adored wife Doreen and the rest of us in his circle, was the charm. When he wasn’t despairing for the end of enlightened civilization, he was funny, generous, and warm. And always fiercely loyal. In some strange alchemy, that signature indignation was not just righteous, it was also exuberant. Bob was one of the happiest people I have known.

Moral fervor, in and of itself, is rarely interesting. But with Bob it was always in service to a genuine and deeply felt idealism. He knew, intellectually and emotionally, what great theatre, and the community that could protect it, would look like. And he was that rare utopian who, with an abundance of energy, determination, and good luck, was able to actually build out his Grand Idea. The term he coined was “the repertory ideal,” and its logic was clean and elegant. Put together a company of professional actors that would stay together for years, not just gather for one show. Plays would be presented in repertory: an actor may play a small role in one production, and a major role in another, and the plays in each season would be tied together thematically. The model for this was the great European theatrical companies: the Comédie-Française, the Berliner Ensemble, the Royal Shakespeare Company.

As for financial viability, well, that would be solved in a single stroke. The professional theatre would be attached to a teaching institution, a conservatory, also modeled on European theatres. When Kingman Brewster, the president of Yale, brought Bob to New Haven in 1967, the Yale Repertory Theatre was born. The new theatre company could rely on the financial support of the university, and in return, the professionals in the company would teach at the Yale School of Drama.

Like all utopias, it didn’t last. And, of course, it never really was utopia. Gradually the performing of plays in true repertory gave way to economic exigencies, the best actors did not stay in the company, and eventually there was a new Yale president who didn’t buy into the enterprise. But in its time, more than 35 years in New Haven and then in Cambridge, it was something special, something outside the hurly-burly of the commercial theatre. Those of us there at the time, being students, found fault with everything, but we all to one degree or another imbibed Bob’s idealism and sense of mission. High-mindedness can be contagious, and it started at the top.

And make no mistake: It was a top-down, authoritarian structure. Bob’s peers were the generation of visionaries who founded the important resident theatres. The Public Theater was Joe Papp. Arena Stage was Zelda Fichandler. The Mark Taper Forum was Gordon Davidson. The Alley Theater was Nina Vance. Yale Rep, and later the American Repertory Theater, were Robert Brustein. These theatres, not to put too fine a point on it, were not run by consensus. The managing director reported to the artistic director. Decisions were made without consulting with a board, with HR or DEI officers, or others.

Yes, Bob could be contentious. His run-ins with the likes of Samuel Beckett, August Wilson, Stephen Sondheim, and Frank Rich, or the Living Theater and the Black Panthers, are legendary. He never shied away from conflict; that’s the stuff of drama, after all. I think he relished the battles, and one thing never changed: his absolute and unwavering conviction that he was right. Most of us live in a much more uncertain world. We sometimes reflect on, even regret, our choices. Bob always charged ahead; the mission was everything.

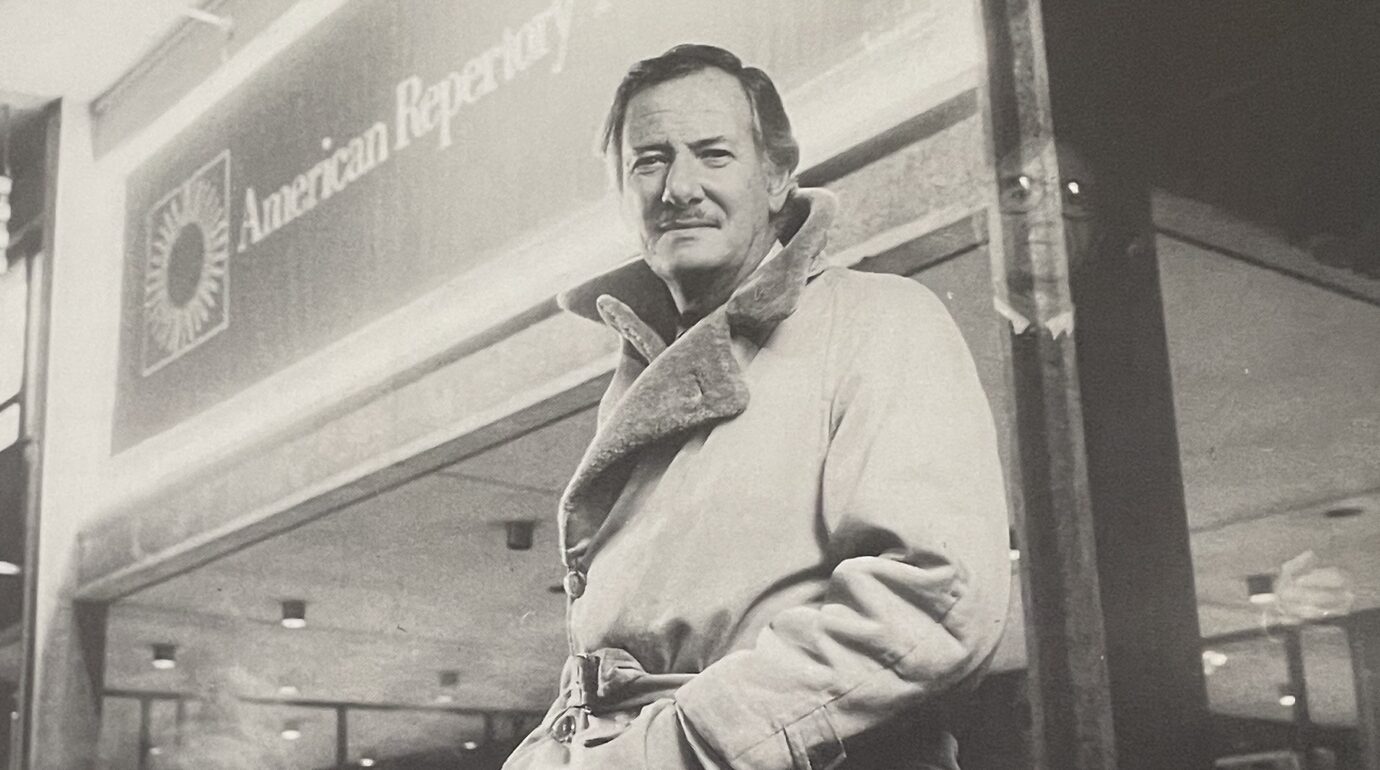

Bob could be exasperating; he wasn’t a great listener, and he could be thin-skinned. But he was a natural leader. His ideal was inspiring, and like all great leaders, he was charismatic. He had presence. Physical presence: He was tall and good-looking, with an actor’s deep voice. And moral presence: His dream was to establish a true theatre community, protected from the vicissitudes of the marketplace. He was an intellectual but at heart a revolutionary. He loved the theatre and the people who make it with all his being and felt that it could never reach its full potential without a safe haven in a mercantile culture. Chekhov wrote, “We must take the theatre out of the hands of the grocer.”

Bob Brustein did that. Gloriously. It was his life’s work.

Rocco Landesman, formerly the president of Jujamcyn Theaters and the chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, spent eight years at the Yale School of Drama as a student and professor under Robert Brustein.