Once upon a time, there was a website update that theatre artists and workers would wait for each year, eager to see whose work would be included and whose wouldn’t make the cut. It wasn’t an award or a fellowship or a commission: It was the Kilroys List, a gathering of the best plays by unproduced or underproduced women, trans, and nonbinary playwrights. And it was, despite the anti-gatekeeping intentions of its founders, a powerful tool in the industry.

At its height, the Kilroys List not only got more eyes on a playwright’s script—it also shone a proverbial spotlight to guide agents, artistic directors, producers, and dramaturgs to overlooked talent. But what started out as a forum to call out the industry’s complacency and amplify the voices of writers over the years became a coveted endorsement that could change lives. The writers on the Kilroys List were cool, the Kilroys themselves cooler, the top of the hipster theatre social ladder. (The non-hipster category was where the storied theatre institutions that hadn’t produced any work on the Kilroys List lived.)

So why would the Kilroys give up this prestige now, three and a half years after a pandemic shut the industry down, and try something new?

“The list was starting to turn into a thing that people were lobbying to be on,” said Gina Young, a playwright, director, and songwriter. “You know, ‘I need to be on this,’ ‘Why am I not on this?’ There was that kind of energy around it.” The Kilroys hadn’t intended to create new hierarchies with their list, but any list will inevitably do so. Once the group recognized this new dynamic and its potential for further fractioning, they had to decide how best to move forward.

They resisted the urge to return too quickly once theatres began reopening after the pandemic shutdown, fearing that a quick reaction wouldn’t take into account a full picture of the industry. “The idea that every two years, theatre is dead, it’s dying,” became a sentiment around which to mobilize, according to writer and actor Bianca Sams. The Kilroys, an all-volunteer group, forced themselves to step back and take what they call a “listening year,” holding meetings with artistic directors, playwrights, and actors, hosting salons, and gathering survey information to discern next steps.

“One of the things we got from this listening year was the amount of hope we all needed,” Sams said. “Everbody’s a little depressed, we’re all a lot afraid about what the hell’s gonna happen on the other side of the pandemic,” she explained, noting the theatres that have shut down and the opportunities that have dwindled for women and trans and nonbinary artists. “How do you continue with that, except hope? What’s going to keep theatre alive is not some institution—it’s the people.”

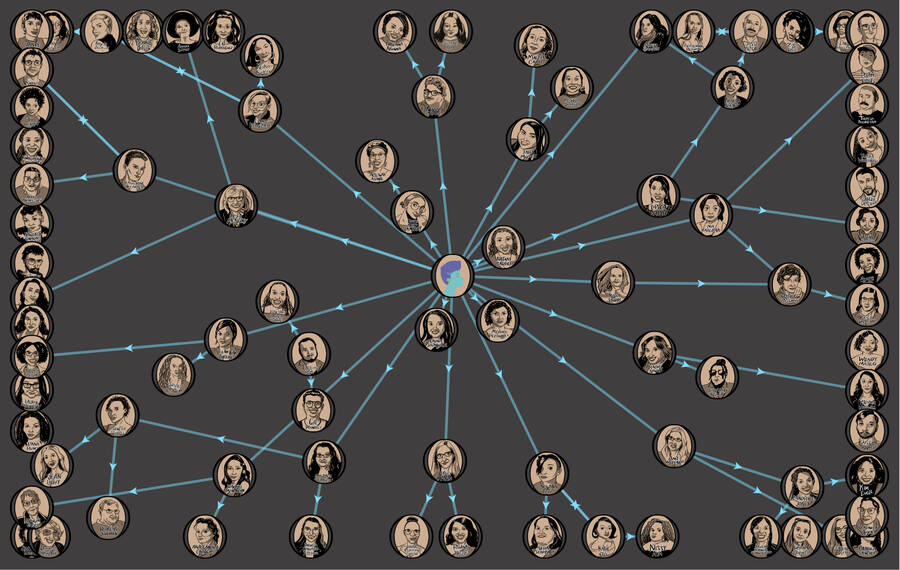

In that spirit, the Kilroys have replaced their list with the Web, a new tool for shouting out and lifting up artistic collaborators. The group invited directors, literary directors and managers, and creative theatremakers from across the U.S. to be Champions of Plays they believe in that are underproduced (one or fewer professional productions), similar to the way list was compiled in previous years. The next step was new, though: The Kilroys then asked the recommended playwrights to in turn recommend two other folks they consider Champions of their work and forces for good in the ecosystem at large. All of the playwrights, their plays, and the Champions they submitted are laid out on an interactive visual Web, complete with cartoon versions of each collaborator, drawn by Vexx Daniel. The Kilroys hope the resulting uplift will be more organic and less competitive. (Though if you want to simply view this year’s list of 39 under-produced plays, you still can by scrolling to the bottom of the page.)

Sams calls the Web a “snapshot of an ecosystem” that doesn’t rank one artist over another. (The Kilroys List represented, for example, the top four percent of unproduced and underproduced new plays by women, trans, and nonbinary playwrights in 2019, and the top nine percent in 2017, based on the recommendations of extensive lists of nominators.)

In addition to amplifying the work of artists, not just playwrights, the Kilroys hope that the Web will inspire similar efforts from other groups of emerging artists, educators, and theatre fans. “We are hoping that people will read what is written about them, and that there’ll be a little bit of virality of people reading,” Young said. “Anyone can thank anyone they want, anyone can talk about who’s championed their work on social media. It doesn’t have to be just what’s on the Web.”

While the goal of the previous Kilroys project was to get more women, trans, and nonbinary playwrights produced, the group isn’t defining success by this metric anymore. Instead of looking for validation from producing institutions, the Kilroys want the Web to uplift individuals and communities of artists, regardless of affiliation.

“For me, it’s always been about the signal boost,” Sams said. It’s about “finding people who believe in the same mission. It’s not about this rubric of, ‘You’re amazing—and you’re not amazing if you’re not on this.’ I feel like that hierarchical thing detracts from what makes theatre worthwhile.”

To that end, the Kilroys emphasized that the new Web exists independently of previously published lists, and that its goal is to cultivate gratitude among theatremakers. Plenty of artists receive widespread praise from their colleagues and the social media community when they win an award or get a new job; far fewer get their flowers in their day-to-day work. The Kilroys List was somewhat stagnant, updated annually or less, while the Web is a continuously evolving, living document of theatre artists today.

“We’ve been very careful to say, This is not a list,” playwright and producer Monet Hurst-Mendoza said. “Everyone keeps emailing us and saying, When are we getting the new list? Well, you’re not getting the new list. Sorry, girlies. You’re getting the Web this year.”

Amelia Merrill (she/her) is a journalist, playwright, and dramaturg. A contributing editor at American Theatre,her work has been featured in Mic, Hey Alma, Narratively, and more. @ameliamerr_