Read our previous essay by authors Mallory Catlett and Aaron Landsman here.

The idea of theatre as a conduit for civic engagement has a long history. The Brazilian activist Augusto Boal formed the Theatre of the Oppressed in the 1970s, which used the language and structure of performance to empower dispossessed citizens. (A dozen actual laws were passed in Brazil thanks to Boal’s theatrical techniques, which he employed while serving in city government.) In the World War-II era, there were the leftist and anti-fascist plays of playwrights like Clifford Odets and Bertolt Brecht. The Civil Rights Movement was aided by the community engagement work of the Black-led Free Southern Theater, and the venerable Living Theatre continues to make experimental, avant-garde shows dedicated to dismantling entrenched power structures.

The late 20th century saw the rise of another kind of theatre-as-discourse: documentary, or verbatim, theatre, wherein plays are constructed out of real people’s actual words, whether culled from interviews, letters, speeches, court records, or other non-fiction sources. The most recognizable practitioner of this form is Anna Deveare Smith, who has often built her plays around moments of violence or racial tension in America. Her now nearly canonical method is to interview people connected to the event and to bring those interviews to life in a chain of monologues (though she has pushed the boundaries of this method in her more recent work).

Plays in this and similar forms inevitably raise the question of how much power theatre actually has to affect change, and how much it can shape the way we relate to each other in the real, rather than the staged, public sphere. Two new books, In the Lurch: Verbatim Theater and the Crisis of Democratic Deliberation by Ryan Claycomb and The City We Make Together: City Council Meeting’s Primer for Participation by Mallory Catlett and Aaron Landsman, both address this question, though they come at it from different directions. In fact, what most aligns these two books is their shared belief in the primacy of posing questions over offering answers. Claycomb, Catlett, and Landsman all seem to feel that entering into difficult conversations, and admitting what we don’t know or are struggling to understand, is the most worthy kind of endeavor—in art and in life.

In In the Lurch, Claycomb tracks his own evolution from enthusiastic cheerleader of verbatim theatre, optimistic about its power to change minds and hearts, to cynical questioner of the usefulness of the form. He was first lit up by his encounters with Smith’s work in the 1990s, including her seminal Fires in the Mirror and Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992. He sets these alongside other standouts from what he sees as a golden age of verbatim theatre, including The Laramie Project, about the murder of Matthew Shepard in Laramie, Wyo., and Guantanamo: Honor Bound to Defend Freedom, in which Gitmo prisoners and lawmakers both have their say.

Claycomb’s personal journey is set against a cultural backdrop. Reexamining verbatim theatre in light of the events of the last eight years or so—the election of Trump, the murder of George Floyd, the storming of the capital on Jan. 6, and the increasing divisiveness of American politics—has shifted his view of the form and cast his prior optimism in a wan light, suggesting his own liberal complacency during a generally complacent time (essentially, the Clinton era to the Obama era).

In the Lurch is mainly a scholarly text, delving into some highly theoretical constructs around empathy, nostalgia, public space, and utopianism. But the most compelling moments are the ones where Claycomb plumbs the depths of his own befuddlement. The title of the book shows up occasionally to mark an in-between space where verbatim theatre now finds itself—it’s been left “in the lurch” by recent cultural shifts—but more often in reference to the rightward “lurch” of the country. Claycomb paints himself as a disillusioned lefty who no longer believes quite so innocently in the power of art to build bridges. He questions not only the verbatim form, about which he once wrote a rapturous dissertation and several scholarly articles, but also wonders searchingly what his country most needs right now, particularly from its artists, to avoid flying off the rails entirely.

It might have been interesting if, in addition to parsing his own doubt about verbatim theatre’s capacity to effect social change, Claycomb had spent some time exploring other theatrical forms, ones perhaps more suited to our fractured times. But instead we are left mostly with—no surprise—questions: “Will the methods of the (neo)liberal pluralist 1990s suffice in the rightward lurch of our recent past? Or does the moment require something other than deliberative democracy…Must deliberation make way for something more intimate and more basic?”

In the Lurch offers more concrete suggestions only on its very last page. Many of the features that Claycomb envisions in this brief forward glance—“immersive performance environments that invest audiences with a sense of greater agency”; “agonistic” performances that stage conflict; “testimonial performances,” wherein actual interview subjects are given stage time—are embodied and explored in City Council Meeting, a play developed by Catlett and Landsman over several years, which forms the basis of their book. In fact, I almost expected Claycomb to give a shout-out to City Council Meeting for its valorous attempt to bring documentary theatre up to date, but alas no.

This omission may simply have to do with the scope of Claycomb’s work, or it may have to do with the success of City Council Meeting itself, which was received with varying levels of enthusiasm by critics and audiences when it toured the country between 2010 and 2014. Indeed, Catlett and Landsman admit in their book about the making of the show that it was a “strange, complicated piece” that challenged and unsettled audiences by design. (John Pluecker’s review for Free Press Houston started with an overheard audience member proclaiming, “This is so weird.”)

The City We Make Together is subtitled a “Primer for Participation”—i.e., a handbook for theatre practitioners or teachers who may want to adapt City Council Meeting for their own troupes or classrooms. The book provides a breakdown of the show, with detailed descriptions not only of each element but also of the development process it arose from. That it takes 200-plus pages to explain the show to an uninitiated reader is a sign of both the work’s complexity and the consciousness and care with which the director-authors approached it, much as they did their book about it.

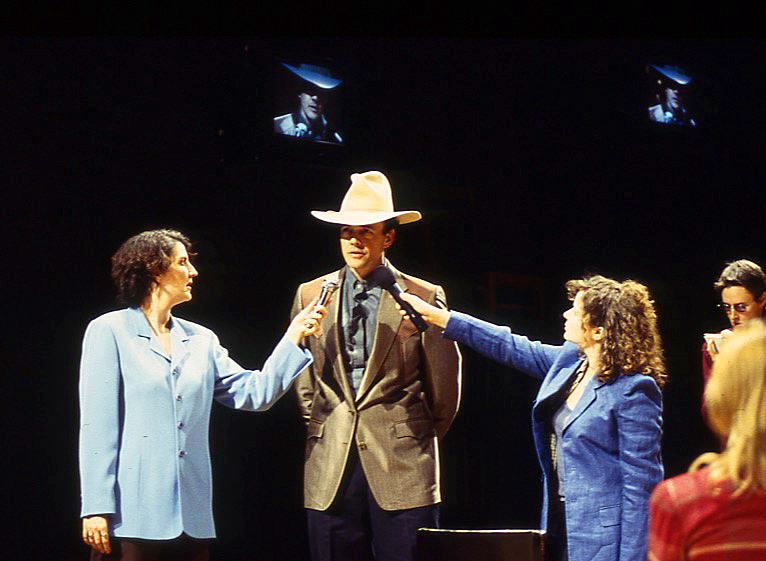

I will do my best to boil it down. The play was performed in five different U.S. cities—Houston; Tempe, Ariz.; New York City; San Francisco; and Keene, N.H.—and was site-specific, responding to local issues in each place. The basic skeleton comprises three main parts: the “meeting,” a semi-scripted play pasted together from real city council meetings and allowing audience members to choose the extent of their involvement in the proceedings; a brief interlude in which a professional actor performs a scripted monologue, based on a speech Landsman witnessed at a meeting in Portland, Ore.; and the “local ending,” a kind of play-within-the-play, rehearsed beforehand with local residents and responding to a specific issue plaguing that particular civic body at that time.

We learn that Catlett, co-artistic director of the New York company Mabou Mines, and Landsman, an ensemble member of Elevator Repair Service and an educator, together with their innovative production designer, Jim Findlay, carefully chewed over every detail of the show: how to involve community members in the most respectful way, which issues to highlight in which place, whose voices to foreground and how. The book embraces the messiness and unpredictability of such an endeavor, even the potential boringness of it—what is more tedious than a local city council meeting?—while also celebrating the fact that the show is truly local, made by and for the people.

Catlett and Landsman, like Claycomb, raise a number of open-ended questions about the potential real-world effect of this theatrical approach. Their vision, they say, was to “reframe local politics as art,” to “put a frame around the act and structures of civic participation and democracy.” This goal is not overtly political in itself, but they do wonder at one point, “Could enacting a government meeting as art allow us more freedom to change the structure of actual government processes?”

But unlike Claycomb, who is interested primarily in a theatre of politics, Catlett and Landsman are more interested in the reverse: the politics of theatre. Referencing not only the practices of Boal but also the philosophies of Plato and Jacques Ranciere and the social-structural theories of Erving Goffman, they suggest the ways that performance mirrors civic processes and infuses everyday life, since we are always performing ourselves on some level. In discussing the “meeting” section, in which unrehearsed audience members are given lines to read, they note that “watching someone read a powerful text without any real rehearsal gave off the same effect as watching someone choose words carefully so that their importance came through.” In this way, they nudge their participating audience members into literal performances of civic involvement.

Neither In the Lurch nor The City We Make attempts to rescue documentary theatre from criticism or lay claim to its special powers, whether aesthetic or sociopolitical. On the contrary, both are highly attuned to its limitations and potentially problematic aspects (the fallibility of claims to “realness” and the dangers of cross-racial enactments, to name just a couple). What both suggest is that theatre remains a fertile ground for experimentation and provocation, especially when it comes to asking hard questions about how democracy works and what the role of the citizen is within larger systems. The important thing, both books suggest—especially given the current American political scene—is to keep pushing the form, to keep testing theatre and seeing what it can do.

Pamela Newton (she/her) is a writer based in New York City and teaches in the English department at Yale University.