Read an accompanying review of August Wilson: A Life here.

I often think of a hyperbolic line from Rob Sheffield’s excellent, companionable book Dreaming the Beatles, in which he effuses, “Being born on the same planet as the Beatles is one of the 10 best things that’s ever happened to me.” This line more or less puts into words the way I feel about how privileged I have been to be alive as new Stephen Sondheim musicals were being made, or to cover Angels in America and Ragtime as new works, or to witness Cornerstone Theater’s pathbreaking productions in Los Angeles.

Also at the top of my gratitude list would have to be that I was around to witness, and bear some witness to, August Wilson’s remarkable playwriting career as it unfolded. It seems clear that Patti Hartigan feels similarly: A longtime critic for The Boston Globe, she first met Wilson in 1987, when she was a fellow at the Eugene O’Neill Theater’s National Critics Institute and he was dropping in on the O’Neill, the crucial cradle of his playwriting craft, on one of the rare occasions when he wasn’t workshopping a new play there. It was still an amazingly fertile time for him as a writer: Fences was on Broadway, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone was making the regional rounds (as part of the unique developmental network that Lloyd Richards, O’Neill’s leader and Wilson’s first major director, had helped create), and The Piano Lesson was set for a November debut at Yale Yep. It wasn’t long after that that he decided to seal what would be his legacy: the 10-play Century Cycle, with a play about African American life in every decade of the 20th century.

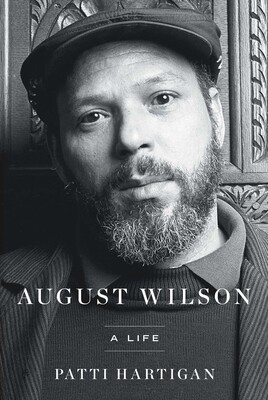

Hartigan would go on to interview and write about Wilson several times in the following decades, right up to the end of his too-short life in 2005. After that point, as she explained in a recent interview, she often wondered why this epochal writer as yet had no major biography. At last she decided to write it herself, discovering along the way that his remarkable life stands in a great tradition—as quintessential an American story in its own way, she told me, as that of Abraham Lincoln or Barack Obama. In his review for this publication, Nathaniel G. Nesmith praises Hartigan’s new book, writing that she “has honored Wilson in the way he deserves.” I concur. The following interview has been condensed for clarity and concision.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: I’ll just start by saying I love the book—I devoured it. It’s a fine work on a great playwright.

PATTI HARTIGAN: Thank you.

I remember seeing the Times story when you got the gig, back in 2017. Had you been planning this book for a while?

I wasn’t really contemplating it. I had taken a buyout from the Globe but was still writing for them, and the Globe magazine sent me out to Seattle in 2005 when he was still finishing Radio Golf and was about to turn 60. He had not been diagnosed yet. I was there for five days and I did a long magazine piece about his whole life. It was the end of an era for him, and he was going to start doing other things. It’s so memorable to me, because it was such a pivotal moment for him, and it was so fun to write that piece. And then, you know, we got the news that he had inoperable liver cancer, and he passed. Years went by and I kept waiting to see a biography. And then in 2016, the Huntington Theatre did a production of How I Learned What I Learned, and it was Eugene Lee playing the August Wilson character, Todd Kreidler directing. Every time I see that play, at the end, when he puts on Borselino fedora and the typewritten names of all the plays come up—I gotta have tissues. I saw that and it occurred to me that nobody had written a biography, so I started on the proposal. That’s when it really germinated.

I haven’t seen that play, but from the way you cite it in the book, it doesn’t sound like he was necessarily a reliable narrator.

It’s a dramatization of a fabulous life, and he knows how to tell a joke, so of course he’s going to exaggerate some of the stories. But the atmosphere of Pittsburgh and the friends he had, that’s all real. The story about Cy Morocco, who played the saxophone—it’s really funny in the play how everybody runs away when he starts to play. I interviewed this guy in Pittsburgh, Dr. Nelson Harrison, who was a sideman for all the jazz greats and also has a PhD in psychology, and he was like, “Oh, yes, Cy could not play at all.”

How many interviews do you think you did for the biography? Dozens? A hundred?

It was more than 100. I got to 30 when I was counting just sources from the O’Neill. Someone asked me to count, but when I got to 110, I just stopped. The silver lining of the pandemic for me is that I couldn’t get on a plane and all the libraries closed, and nobody wanted to talk. So I had to write the book.

That quantity of interviews obviously helped you gather some great anecdotes and details, but I wonder, did it also create some Rashomon situations, where the more folks you spoke to, the less certain you were about some things?

Oh, that’s interesting. Well, the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center was fairly easy to source, because I was there in 1987 as part of the National Critics Institute, and once you’re a member of that family, you’re a member. So I would talk to one playwright, who would then tell me to talk to three more playwrights, and it just snowballed. And because I had been there, I knew what the place was. I did find out a few things that surprised people, because playwrights exaggerate.

As I continued, I put things in folders; I had a Pittsburgh folder, I had a family folder, I had a St. Paul folder. The O’Neill folder was huge. And I had one for each play as well. So when you go through all of them, you just reach a sense of truth. That’s how I did it. Mark Whitaker, who wrote a book about a sort of Harlem Renaissance in Pittsburgh, called Smoketown—he had a banker’s box for each chapter. That’s kind of what I did with my files on my computer.

Obviously a lot of his theatrical career was documented, and many sources are still alive. I was curious, though, how you reconstructed as much as you did of the story in the opening chapter about his great grandmother, Eller Cutler, and a mysterious shooting involving a single white farmer, Willard Justice, she may or may not have been involved with, in North Carolina in the early 1920s. It’s very evocative, and of course it sounds a bit like a story from one Wilson’s plays.

August’s cousin, Renee Wilson—I talked to her early on, and she had a project of finding out the family history on both sides of her family; she was an amateur genealogist. I started doing it too. You can go to courthouses, get documents, go on ancestry.com. It’s a lot easier now than it used to be. So we gathered all this information and she and I went down to Cedar, N.C. She found a local, and we actually climbed up to August’s great grandmother Eller’s homestead. This local, I don’t know old he was, but he used to play on that mountain when he was a kid, and his parents would tell them who lived where, and he led us to it. That’s when he mentioned the folklore of the story of Willard Justice. When we got back to the place where we were staying, we immediately started researching the death certificate and found documents from the court. Part of the challenge with documents from that period and before is that enslaved people are listed by characteristics sometimes rather than name, so you’ll have things like “blind man” or “5-year-old boy.” I’m very clear in the footnotes that we can’t be 100 percent certain about the history.

What shivers my spine is when you discover things that appear in his plays, and he most likely didn’t know all the details about his great grandmother on that mountain—he said many times that his mother, Daisy, and her siblings, that generation, didn’t want their children to know what they went through. They wanted to raise them the same way as Berniece in The Piano Lesson, with hope for change, and to put the past behind them. The blood’s memory really coursed through August. You also have to remember that the man read everything ever written—he was an autodidact. But he didn’t specifically research and say, “Okay, I’m writing a play about this era…”

I want to ask about your approach to various controversies and conflicts he faced: His split with his longtime director and mentor Lloyd Richards, his feud with Robert Brustein, the shocking story of how James Earl Jones tried to use the producer of Fences to change the play, the marital infidelities. How did you decide how deep to go into these, and how much dirty laundry you needed to air in some cases to set the record straight?

What I tried to do was to create a full picture of the man, who was a genius but who, like every genius, had a few flaws. Everybody does. I didn’t want to accentuate them, but if they were important to the story of his life, that’s when they emerged.

I did notice in the back of the book a note saying that Wilson’s estate “declined authorization.” What’s the story there?

So I decided that I wanted to do this book and I asked the estate for authorization. I was granted authorization. I went to the opening of the film of Fences at Lincoln Center, and I was introduced as the biographer. And then agents got involved. There were a bunch of agents and lawyers in rooms; I had nothing to do with it. But the requirements of the estate were things I couldn’t agree to, that no writer could agree to. And so we parted ways. I had to do my job. And I wish [Constanza Romero] peace.

One thing the lack of authorization meant is that you couldn’t quote as much of his poetry and early plays as you would have liked.

Yeah, when I had to paraphrase poetry and letters and unpublished plays that I dug up in the archives—there were tears on the cutting room floor along with the words. Because I can’t paraphrase August Wilson! It was tragic.

I think you wrote around it very well. You also mention in the book how you just missed talking to Marion McClinton, who had a long association with Wilson’s work and directed some of his later plays.

He was very ill. He said he wanted to talk to me, but he kept putting me off and putting me off, and finally his ex-wife, who he still had a relationship with, called me and said, “He’s going to do it the weekend of Thanksgiving.” Then she called me that Thanksgiving night—I was gonna fly that Friday—and said he’d passed. I knew that the clock was ticking as I was doing this research. Anthony Chisholm died, Mary Alice died, Terry Bellamy died. I mean, I could go on. You have this memory walking on the planet, and you’ve got to get it while it’s still there. There was a sense of urgency.

In the original Times piece, you addressed the fact that you’re white. August famously insisted on Black directors for his plays and for the movie of Fences, and presumably would have had thoughts about who he would have wanted his biographer to be. I just wanted to ask your thoughts about writing with authority about a man who, while he had his own complicated issues with race, fully embraced a Black identity.

This book needed to be written. You know, Jonathan Eig was interviewed in The New York Times about his Martin Luther King biography. He was asked the same question, and he said: You simply work harder. You have to get your facts right. You have to talk to everybody, and you have to tell the story with dignity and with the respect that it deserves. So I stand by my work.

One thing I especially appreciated was how you laid out the unique network of regional theatres that Lloyd Richards helped set up to develop August’s plays—something no playwright really had before or since to that extent.

Yeah, some people called it a circuit, and it really began at the O’Neill. There was criticism of this model, of course, but I believe it was Michael Maso who said, when Joe Turner’s Come and Gone was going to be at Huntington, “Look at Broadway, at the commercial theatre—you think opening a play at the Colonial Theatre in Boston, having it bomb and then never going to Broadway is helping the theatre?”

One quote of his jumped out at me. You record him wishing that “every regional theatre would commit themselves to not to plays, but to a playwright,” which isn’t quite the deal he had. But interestingly, abou 10 years ago the Mellon Foundation did start a program install resident playwrights at several regional theatres.

Yes, Melinda Lopez is the resident playwright at Huntington. But remember, Paula Vogel was a resident at Arena Stage long before that, and Suzan-Lori Parks is still at the Public.

You’re clear in the book that Joe Turner is your favorite Wilson play, as it is mine—it’s not an uncommon opinion. What is the best Wilson production you ever saw?

Joe Turner at the Huntington, with Delroy Lindo and Ed Hall. It was just phenomenal. I was a critic for a tiny local newspaper called The Tab, and I remember sitting in the theatre during the scene with the bones walking on the water. It was one of the most memorable nights I’ve ever had.

As the Century Cycle unfolded, I began to feel the weight of the responsibility to cover all the decades and to say something significant seep into the plays. Reading the biography, it seems clear that it also weighed Wilson down a bit. Did you feel something similar after spending all this time with him?

I pretty much wrote it in chronological order. And the day that I had to write the funeral scene was a day that I cried. Six years is a long time to be working on one thing. But I had to. And I hope I did it justice.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre.