This is one of two features inspired by the untimely end of Seattle’s Book-It Repertory, which closed suddenly in late June. The other story is here.

It’s Tuesday, June 27. We are in the bowels of tech for Hedwig at ArtsWest in Seattle. Shortly before noon, my phone begins to buzz. Condolences and messages of support flood my screen. I don’t know what’s happening at first. Information stumbles around the room as texts, emails, and hushed conversations confirm: After 34 years, the board of Book-It Repertory has decided to cease operations.

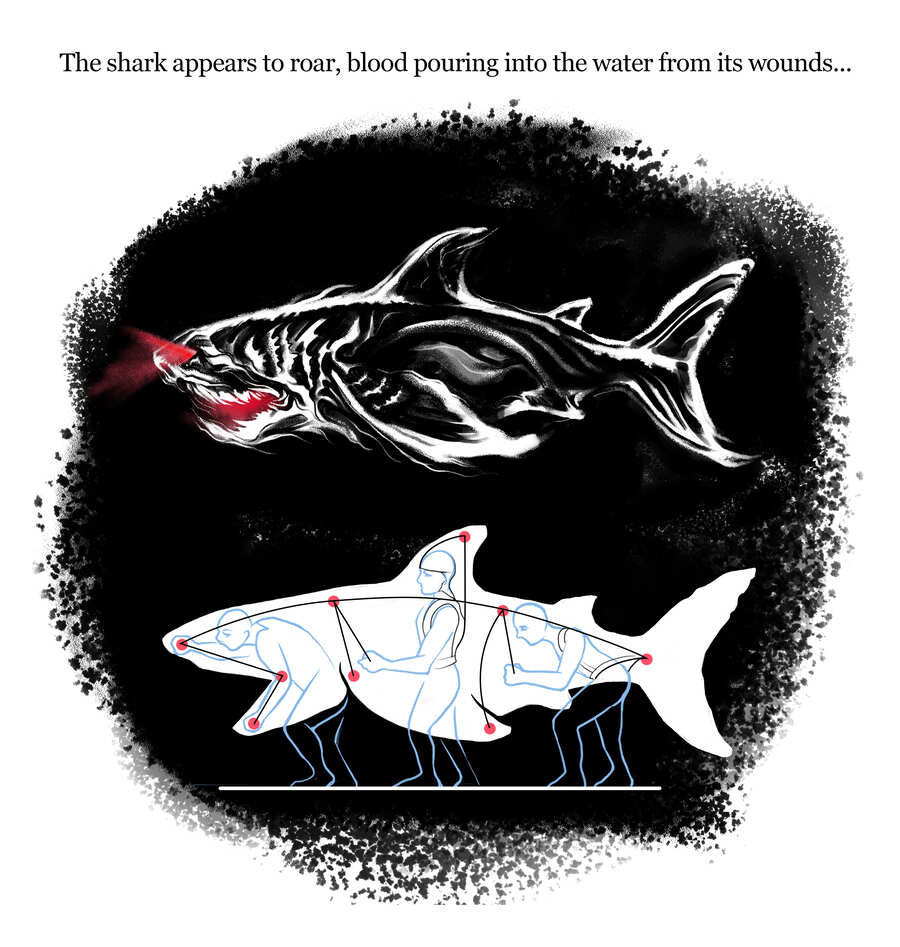

I am a director, writer, and visual artist who spent the last year translating and adapting Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas into a new play for Book-It’s 2023-24 season, which I was slated to direct (and design puppets for) next spring. Three weeks prior to this sudden closure announcement, we had a first read and began the process of casting an all trans/nonbinary and female team. I feel unmoored by the news of Book-It’s demise, and I’m not alone. While I now live in New York, due to the tight nature of the Seattle theatre community, almost everyone I know there is affected.

“I keep thinking about what to say and all I keep coming up with is, I’m just really sad,” Jéhan Òsanyìn writes me. Jéhan was slated to direct Book-It’s fall production, Frankenstein, and their response mirrors those of other artists I reach out to. Overwhelmed as waves of cuts and pauses in the larger theatre field disrupt livelihoods and destabilize communities, we go quiet. In Peter Marks’ recent article, he paints a bleak picture of the causes of this turmoil, and Larissa Fasthorse points out in her article about her show being cancelled by the Mark Taper Forum that it’s also happening in a moment when artists who were historically marginalized are stepping into their power—only to be handed a mess.

Our generation has survived so much. Artists who should be flourishing are struggling to make ends meet. Through recessions, the rise of mass shootings, 45, the pandemic, we are the walking wounded. In 2023, I can be legally discriminated against in 19 U.S. states because I am trans. I worry for us. I worry for those who will lock themselves away or throw their hearts into the sea.

Strangely, looking toward my canceled project is where I have found solace.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was a dream project, as a writer and director who loves to craft visceral, transportive experiences. Sharks, shipwrecks, giant squids, morally complex ethical dilemmas—the book had it all! And it is beautifully grounded in the strange intimacy that forms between its two main characters: Professor Aronnax, a curious and open-hearted scientist, and Captain Nemo, a vigilante antihero. When they meet, Nemo has severed his ties with humanity and lives in a futuristic submarine called the Nautilus where he explores the ocean’s depths. Nemo looks up to heroes like abolitionist John Brown, and condemns imperialism, environmental exploitation, and systemic oppression, collecting sunken treasures to fund slave rebellions and righteous causes all over the world. It’s actually very badass.

His motto is “Mobilis in Mobili”—moving in a moving medium, or as I have begun to think of it: to be alive in a living world.

As storytellers, we do not write history—we feel it as it lives around and through us, and we translate this to story. Our ancestors too gathered in dark caves by flickering firelight because stories are intrinsic to who we are, who we were, and who we want to be. Each telling grows our living mythology, which becomes a vast mycelium rooted beneath us, which we have to care for and nourish.

Here’s part of my mythology: When I was 7, I was thrust into the French school system without any knowledge of the language. My teachers shamed me and my peers bullied me, and I did not think I could survive. I hid in the library. There I read graphic novels and adventure books, and through them slowly taught myself how to read and speak fluent French. 20,000 Leagues was one of those stories.

As an adult learning how this story weaves into me now, I find an intimate meditation on grief, loneliness, resistance, and resilience. I find a loving but honest portrait of a man who can face anything and everything but his grief. It is the only thing he cannot move through. And because grief is a living thing, he tries to deaden himself to kill it. He locks himself away and shuts out Aronnax. But still his grief lives. So he lashes himself to the top of his ship in the direct path of a hurricane, and screams into the raging storm. For all his bravery, Nemo would rather face a hurricane than himself. He would rather die than live through the transformation he would undergo if could live with his grief.

Where I find comfort is this: Aronnax stays with Nemo through the storm. He compassionately bears witness to his grief, and where it cannot live in Nemo, it finds a home in Aronnax, and there it flourishes. Alive, it lives in him, and he lives in it. And though Aronnax must eventually flee Nemo, he chooses to nurture his story, growing it into this almost impossible wish:

If Captain Nemo is still dwelling in the ocean—his adopted home—may the hatred be appeased in his fierce heart! May his contemplation of all those wonders snuff out his desire for revenge! May the executioner fall away, and the student emerge in a peaceful exploration of the seas! If his destiny is strange, it’s also sublime.

More than 150 years ago, Jules Verne wrote these words, and I feel them alive in me. It feels absurd and a little foolish, but if I live with my grief, then I also must live with my hope, and they chase each other in endless circles. I share this in hope that when you find yourself unable to move, to face things, to live… that knowing that someone else is with you in the storm might make it liveable. And who knows then what will emerge? Because ready or not, we are going to need to build a new mythology for whatever comes next.

Eddie DeHais (they/them) is an award-winning Franco-American director, writer, designer, and choreographer with an 18-year history building wildly visceral experiences in theatre, opera, and interdisciplinary events. Their body of work is marked by its transformative nature, imaginative playfulness, fierce compassion, and strong sensorial visual aesthetic, crafted for audiences hungry for an authentically alive experience. eddiedehais.com