Though it’s one of the nation’s oldest big cities, Boston was a relative latecomer to the U.S. regional/resident theatre movement. As the Huntington Theatre’s outgoing managing director Michael Maso explained to me recently, it took the town’s universities to invest in theatre production for the place to finally, suddenly, in the early 1980s, birth two nationally significant LORT-level theatres (the Huntington at Boston University, American Repertory Theatre at Harvard). Maso, who recently left the job after 41 years, has been there from the start, working with a total of four artistic directors (Peter Altman, Nicholas Martin, Peter DuBois, and Loretta Greco) over an eventful tenure that included the rescue of the company’s historic theatre from sale, the construction of the Calderwood Pavilion, and the sudden resignation of the previous artistic director in response to community concerns.

I spoke to Michael recently about the ups and downs of his career, the things he’s most proud of, and what’s next for the theatre and for him.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: I’ve talked to a lot of theatre leaders who were looking at the offramp before the pandemic, then decided to stick around through that crisis before leaving.

MICHAEL MASO: That was exactly our thinking—with one additional issue, which is that we were in the planning phases of this major renovation of the historic Huntington Theatre. That was certainly an added incentive, to stick around and see that through. Also, reason No. 3 to stick around: to spend a year with Loretta.

I’ll ask you more about your history in a second, but right now, the question on everyone’s mind is about the present. How’s business? Are audiences coming back?

We are deep into a planning process which should result in about a three- to four-year plan, and that’s designed to create a stronger and a healthier business model. Our renovation is going to add about 14,000 square feet to the space, which we think is critical to the future of the theatre. We have an arc that we are working on, which I think will be enormously helpful in getting the Huntington to where it wants to be.

But right now there’s no question, we’re still working on bringing audiences back to where they were. We came back in the game in the fall of 2021, though only at the Calderwood Pavilion; we produced at our smaller spaces for the year and really didn’t get back to the larger house until fall 2022, and even then it’s been a reduced schedule, in part because of other supply chain issues and delays. And once we opened, we still had work to do, and we went back to try to finish that work. So it’s been a very unusual year. The goal is to start to get back to normal patterns again starting next year. But, as you can imagine, I don’t think that happens in one moment.

Going back to the beginning: What was the Huntington and the Boston theatre scene like when you started out, and where were you in your life?

Well, 41 years ago, I was 31 years old. I had spent two years at Alabama Shakespeare as the first person in the title of managing director, working with Martin Platt, who’d founded the theatre. The Huntington was founded by Boston University in 1982, and ART had been founded about a year earlier or so, after Bob Brustein led his merry band from Yale to Harvard. Boston was really the last large city that hadn’t had an established resident theatre company. There were a couple of smaller companies, one of which survives—the Lyric Stage—but there was also the Theatre Company of Boston, this legendary space with Al Pacino and Paul Benedict; Sara O’Connor was for some brief amount of time the manager of that theatre, but it just didn’t survive. I think it’s fair to say that Boston wasn’t very nurturing of small companies, the way that South Coast Rep, say, started in a storefront, grew in three iterations, and became a major institution. No one was able to grow from a storefront, from an artist’s conception idea into a major institution, in Boston. It really took the universities: It took Harvard to support ART, and BU to support the Huntington, to start these institutions at a scale where it could really grab people’s attention and start to build this structure.

The other thing is, there were no new facilities. When we built the Calderwood in 2004, it was the first purpose-built theatre for public consumption that had been built since what was then called the BU Theatre had been built in 1925. It had been 75 or so years! So it was almost a frozen bit of time in Boston for theatre before the two of us came around. And the Huntington got enormous attention that first year; it could not have gone better. The reception was sort of rapturous, and that established the fact that suddenly, where before there was no large professional theatre in Boston, suddenly now there were two. I think that was healthy. And we were so different, and continue to be different, from the ART. It was really good for this community.

Glancing back at the theatre’s production history, it looks like the first artistic director, Peter Altman, focused on classics early on, but at some point you started to develop new plays also. Can you talk about that transition?

We were doing a lot of, I think, extraordinary work with classics, and the audience was so extraordinarily committed and attuned to it. You’re reminding me: There was a production of St. Joan, directed by one of Peter’s strongest colleagues, Jacques Cartier, who had been the original founding artistic director of Hartford Stage and was teaching at BU. Maryann Plunkett played Joan, and Jacques directed this extraordinary collection of of actors. It was one of the things that the Huntington could do at that time that I don’t think was being done, certainly not better than that, anywhere in the country.

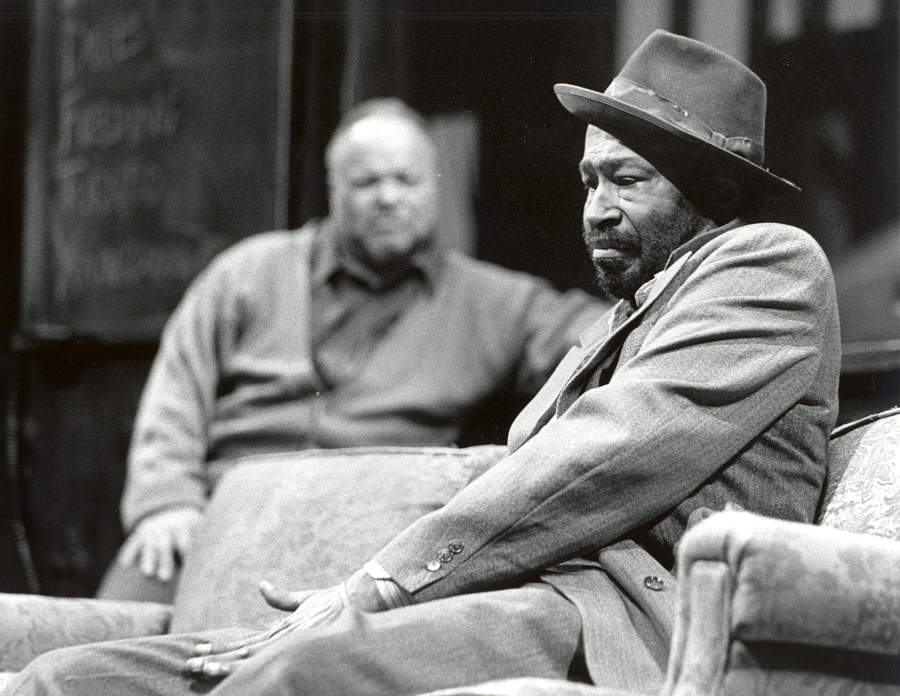

Then one day in in 1986, Peter called me up and said, “I just saw this play at the Goodman and we have to do it.” It was Fences. I called Ben Mordecai, who was then my colleague and friend at Yale and said, “Peter says we have to do Fences,” and Ben said, “Well, you can’t do Fences, because it’s going to Broadway. But August has written another play, would you like to talk about that?” Peter and I went down and met with Lloyd Richards and August and Ben Mordecai to talk about Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. And that started our commitment to August Wilson, which was profound and rich, a mutual admiration society.

Peter had—still has—eclectic taste. He had an eye for talent; he recruited Mary Zimmerman to direct, Kenny Leon, Sharon Ott, Carey Perloff. Those were pretty heady times.

Your second artistic director, Nicholas Martin, stepped up that element of the theatre’s work, right?

Yes, it was Nicky who got to initiate the Calderwood and really up the ante in terms of our commitment to new plays. It was under his tenure that we really expanded, and this started the whole cycle of the Huntington playwriting fellows, which has gone on now for 20 years of work, with a commitment to local writers, to women and writers of color. And we had this extraordinary run when Nicky and Nathan Lane were talking about wanting to work together, and Nathan came and did Butley. I have a lot of memories of being in the back of the theatre, watching shows, often standing there with artists. And I was standing in the back of the house with Simon Gray, and he’s watching a preview of Butley, and he just whispers, “This is the way I’d always imagined it.” That’s a good moment.

During the summer of 2020, the We See You, White American Theatre document identified systemic inequities in the field and demanded changes, and there was also an online campaign by artists and others who’d worked at the Huntington calling out power imbalances, racism, and other workplace issues at the theatre, which led to the resignation of artistic director Peter DuBois that fall. What can you say about that time? Did you feel called out, personally or institutionally? And apart from Peter’s resignation, how did the Huntington respond?

Aside from the fact that there was a moment when there was a list of many of us who work in the theatre and our pictures being circulated—even that I didn’t take personally. Honestly, I never felt personally called out. When I read the [We See You] document, which was maybe 32 pages, it certainly didn’t seem that anyone was saying that every institution is guilty of these concerns. It was a very expansive document. What I felt was that I could look through it and say: Here are five things that I’ve learned, but here are these other things that are being addressed, that I don’t think apply to the Huntington and the way we’ve operated. Obviously, in the context of enormous turmoil, everyone had to decide what their response to that turmoil was and how we were going to address our institutional culture. Peter’s choice was on the record and in terms of what he felt would be best for him and the institution.

The biggest thing for us is a workforce and work-life balance issue. On a staff basis, what are we doing to make sure that we’re building a staff that is equitable, and building a staff culture that is supportive? Not only of the artists, but of everyone who works in our institution? And how do we make sure that we’re providing opportunities to everybody as part of the institution, as opposed to simply onstage? That was, honestly, what we took that to heart. I thought those were fair criticisms, and we’ve taken steps to address them.

There were some highlights of Peter’s 12 years there as well.

Yes: He gave Billy Porter three gorgeous directing assignments, produced and directed Lydia Diamond, Kirsten Greenidge, Chay Yew. And Peter and I brought over the Merrily We Roll Along from London, the one that was just at New York Theatre Workshop and is going to Broadway—we worked extraordinarily hard, without subsidy, without enhancement, to bring Merrily to Boston, and Jim Nicola will tell you that the reason that he wanted that show to be his last one at NYTW was because he came to Boston to see it. So Peter did some really strong work during that period of time.

Loretta’s focus is very much new work, is that fair to say?

You know, we announced her hiring in March 2022, and within that weekend, she saw four productions by other companies in Boston. She is deeply engaged. What’s interesting is that Loretta is a director, but she is by nature and by personality a producer. We had another show scheduled for this timeframe, and when that fell through, she suddenly realized that the rights to The Lehman Trilogy were available, and she instantly pulled in Carey Perloff to direct it. And the same thing is true with shows we’re doing next year; we’re doing The Band’s Visit in partnership with SpeakEasy Stage. I think Loretta understands the balance between the challenge of filling the big theatre and the commitment to new work as it progresses. I think she was an inspired choice, and she’s going to do remarkable work over the next couple of years.

You’ve mentioned a number of shows and milestones. Can you name any other highlights of your time at the Huntington?

There’s no more profound relationship than almost 20 years of really close work with August Wilson. That was extraordinary; that was a privilege. I said the other day: I’ve spent 40 years sort of on the periphery of genius, and that that was a great, great privilege, to support artists like that and share that work with the community. I’ve also loved the whole series of musicals we started with Animal Crackers 35 years ago, with no concept of enhancement; we just did it. We did two Candides, one by Larry Carpenter and the other by Mary Zimmerman.

And Nicky, I thought, was a genius as a director. I remember when we were recruiting him, I went to see his production of Betty’s Summer Vacation at Playwrights Horizons. You know, there are very few productions that one can say, “This was perfect,” right? That one was; it was like this extraordinary tightrope. I think that’s true of every time Nicky got involved with Chris Durang. We did that in his second season with Andrea Martin. But Nicky was just as gifted at the classics. We started his tenure with Dead End, which he had done at Williamstown; we did a production of The Rivals which was spectacular.

The problem is, I have too many things to remember, because I’ve been doing this too long. I do think that building the Calderwood changed the Huntington’s relationship to our community. Because it’s a public service—it is a structure mostly used by other performing arts organizations in Boston, not the Huntington, but it is subsidized by the Huntington. If you ask me what’s changed, that’s it, and it’s one of the reasons that the Boston theatre community is so much more robust and stronger and more interesting than it was 40 years ago. I’m very proud of that.

After 40 years at this job, what are you going to do now?

The good news is, I don’t have plans. There are a few projects that the Huntington, Loretta and our board leadership, want me to stay involved in—technical things about the building and tax credits. I’ll do a little bit of that. And the notion of actually sitting down and reflecting about my time—I have some writing I want to take a crack at. The question is, are there stories I have to tell? I’ll figure that out.

You know, I don’t think I’ve sat down with, and really spent a lot of time investing in, my own thinking or my own creativity in 50 years. I’m looking forward to doing that. Paula Vogel has said, “I will give you the trick to discipline.” She’s promised me. My wife and I are on Cape Cod a lot; we have a house in Truro and Paula and her wife Anne have a house in Wellfleet, and she said she’s gonna give me the trick.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre.