It has become a cliché that even Ronald Reagan couldn’t survive in today’s MAGA-fied Republican Party, though I think that view probably overestimates his ideological purity and undersells his political opportunism and savvy. Granted, a hypothetical latter-day Reagan couldn’t run his 1980s-vintage neoliberal playbook and win a GOP primary today (cf. Nikki Haley). But it’s not at all hard to imagine the former actor and consummate fantasist tailoring his politics to a more nativist, protectionist party, or at the very least going along with it, the way the majority of current Republicans are on board, to varying degrees, with the atavistic demagoguery of Donald Trump and his surrogates.

But Dwight D. Eisenhower? The name is a callback to a whole decade, and to a Republican Party that may have finally expired with the death of Colin Powell, another four-star general who spent time on the political stage and who followed a path, like Ike, that honored old-school military values of duty, integrity, and loyalty—as well as a certain distaste for politics that, in Ike’s case, made him an unlikely president, let alone Republican. To hear his plain-spoken voice again in 2023, as we have a chance to do in Richard Hellesen’s new play Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground (now at the Theatre at St. Clements through July 30), is almost disorienting, as if we’re tuning into an alternate timeline rather than our own mid-20th-century history. Were our national leaders ever really this decent, this fair-minded, this bracingly average? Maybe the fun-house mirror of our present-day politics distorts our still extant civic virtues, and effectively despoils the common ground we might still claim if only we could lower the temperature of our rhetoric; on the other hand, it’s entirely possible that ours are exactly the politics a nation ever in denial about its unequal past and privileged present deserves.

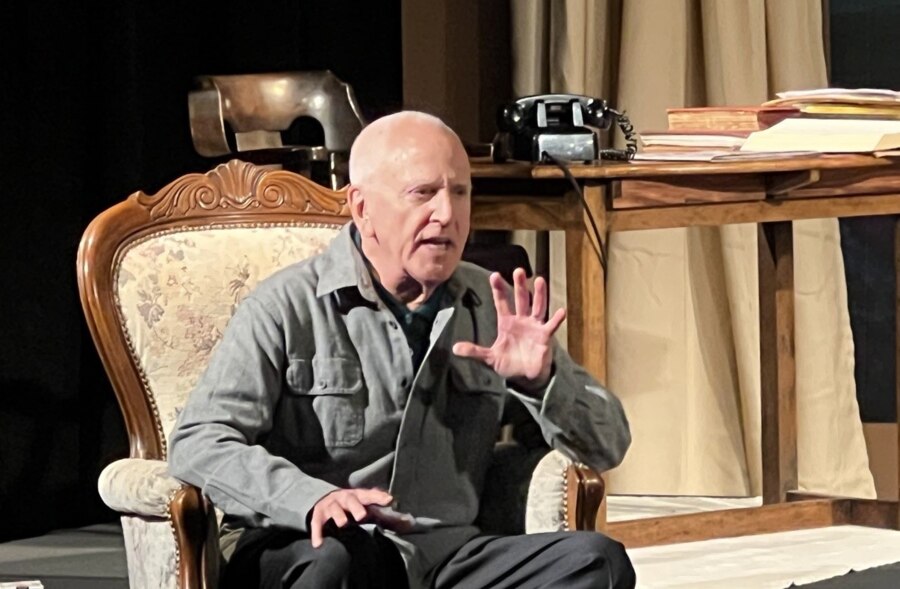

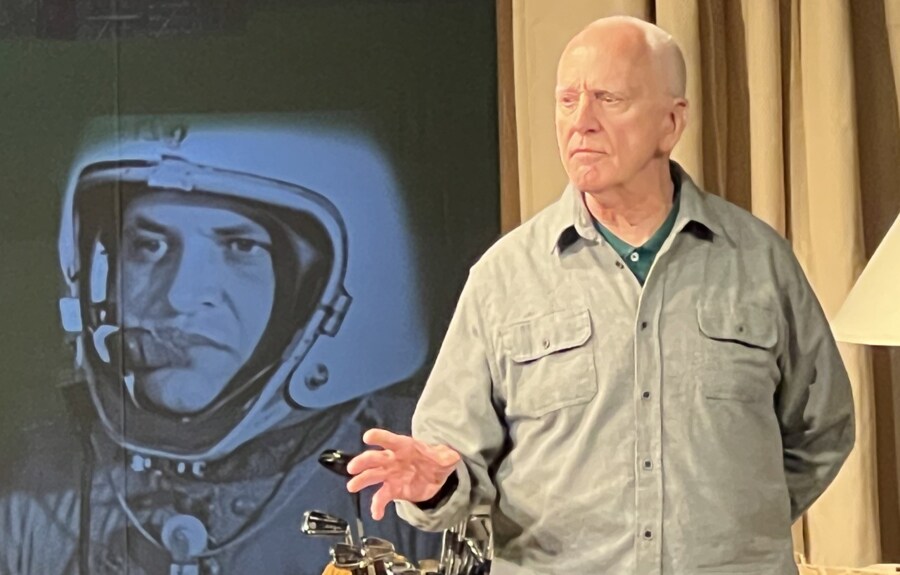

Hellesen’s play, a one-man show enacted by shiny-pated Broadway veteran John Rubinstein, won’t settle the question of our currently dysfunctional politics either way. Styled as a monologue in which Eisenhower responds—first tetchily, then philosophically—to a 1962 historians’ poll that has ranked his presidency 22nd of out of 31 (he’s shot up into the Top 5 since then), and sets out to record his side of the story on a cassette deck for posterity, it is anchored very much in its uneasy Cold War moment, even as it can’t help but reflect unflatteringly on our own. It’s an era Rubinstein, who originated the role in a well-reviewed run at Hudson Theatre in Hollywood last fall, has some firsthand memory of. I spoke to the Tony winner (known roles ranging from Pippin to Children of a Lesser God to Ragtime) recently by Zoom about his approach to the role, what he’s learned about Ike and American politics, and where things all went wrong.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: Had you ever done a solo show before this?

JOHN RUBINSTEIN: No, and for about 25 years, I have been looking for one, just thinking that it would be fun to do. I have lots of friends, actors, who have their one-person show; they travel with it, they do it at universities. I always thought: Okay, I play the piano and I sing, so probably it’s me sitting at a piano and singing something not from my career—you know, being Cole Porter or somebody like that. But then I look it up and everybody does that, and much better pianists and much better singers than I am. So I said, okay, I’m sort of hooked into the classical music world through my dad and my whole upbringing, and, you know, Mahler is a very interesting person. Maybe I’ll be Mahler and I can play some themes from his symphonies or whatever. I found a playwright, and we sat and we talked and he was excited, but then he got other jobs and other gigs, as we do in this stupid business. I thought, for some reason, Herman Melville. I love Herman Melville, so maybe I can be Herman Melville, and I can talk about Moby Dick and all kinds of other things.

Then the phone rings and it’s this guy, Peter Ellenstein, who has directed a lot of stuff in L.A., and I had met in Kansas, where he was running the William Inge Festival; I did that twice, once to honor Garson Kanin, and years later to honor David Henry Hwang. Peter called me up out of the blue and said, “I have a play about Eisenhower, and I’d like to send it to you.” I read it. It’s 40 pages long and it’s single-spaced, one guy talking. I thought, Jesus Christ, I don’t know if anybody’s gonna want to hear that. But he said, “Why don’t you come and meet with me and the playwright, just the three of us in a little room, and read the play out loud?” I said okay. I grew up in the Eisenhower years—I was a little boy, but I remember him. I even met him even once at the White House.

When your father played there, right?

Yes, and a friend of my father, Sherman Adams, was his chief of staff, so Sherman arranged a meeting. My parents and my sister and I went to the White House. We toured through the White House, then we came into this room where he was meeting a bunch of people. I shook his hand and he said, “It’s nice to see you, young man,” that kind of thing. He talked to my dad for a long time.

But I listened to his voice on YouTube, several speeches and interviews. He was born in Texas but he grew up in Abilene, Kans., and I sort of got that sound. It’s not a Rich Little kind of impression, but it’s very much the rhythm and the cadence and the sort of accent that he had. Armed with only that, I came and read the play out loud and realized, this is really a great play. This is not a lecture about history. This is a drama about a man going through a particular conundrum on this particular day. We follow him through it as he remembers his life, and he relates it to the present. It’s very dramatic and very moving. Of course, you do learn a lot about him, but the direction of the play is a man trying to grapple with what he stands for. So it gets very deep and very emotional. I just think it’s a brilliant piece of writing, and I feel honored to get to bring it to audiences.

Apart from that brief meeting, do you have any memories of Eisenhower as president?

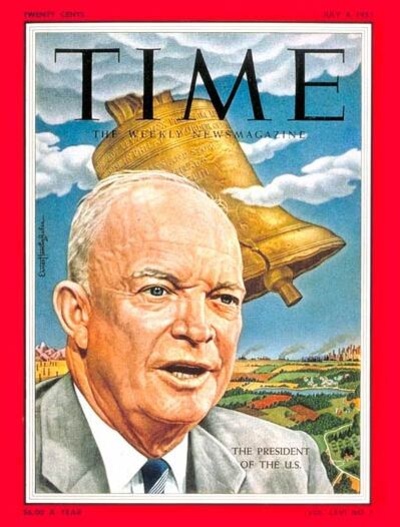

They’re pretty vague. In 1952, when I was in second grade, I wore a little “I like Ike” pin, but I didn’t know what the hell I was talking about. He was just a very avuncular sort of man; you’d see him on TV now and then you’d see his picture on Time magazine. He had been a hero in the Second World War. There was this whole Suez Canal deal, and I remember Little Rock, absolutely—the children being guarded by the 101st Airborne as they went to school, just because they were Black. But my impression of Eisenhower was that he was really just a nice old guy playing golf who was in charge of the country. And we were in good hands.

I always think that mild slogan, “I like Ike,” sums up his appeal perfectly. It’s hard to imagine anyone saying they loved or hated him. He didn’t inspire great passions, except among some pretty fringe figures.

I wouldn’t say they were fringe characters, given what I’ve learned in playing this role. He was fighting the whole time. Similar to what Joe Biden is going through now. You know, Ike became a Republican, not because he was an avid right-winger—he was a middle-of-the-road guy—but just to stop Robert Taft from getting the Republican nomination. Taft was an isolationist and Eisenhower feared for the country. That’s the only reason he was a Republican. Once he was elected in a landslide, middle of the road was always his approach to governing. That infuriated the right wing of his party, which was not a tiny fringe. So he was fighting them tooth and nail, and he also had to fight the Democrats, because he was a Republican. So he was really up against it.

That may have been true behind the scenes. Publicly, though,and for better and worse, it wasn’t an era characterized by constant partisan battling and by constant all-or-nothing brinksmanship, as has been the case in American politics for a lot of my lifetime.

Well, he was a gentleman, which is why people thought of him as just Uncle Ike, just a nice old guy. But he was deeply committed to being a decent human being, and he felt that reflected the good of the country. He felt, as the president of the United States, just as when he was commander of the invasion of Europe and was sending soldiers into deep danger, that if you yourself don’t firmly abide by moral standards that are fair and just, then that would be reflected in what happened to your country. So he was a good man on purpose.

I will say, and I’m partly stealing a friend’s ideas here, that there really has been no one else like Eisenhower in modern American politics—i.e., he was a war hero, a former general, who nevertheless didn’t have a trace of Caesar in him. Quite the contrary. Around the world and throughout history, that has not typically been what happens when a military figure takes a nation’s top office.

Right, they’re military guys who are used to giving orders and people have to obey. But that’s not the president’s role.

He shows flashes of anger in the play that remind me a bit of Key & Peele’s Obama anger translator sketch. Ike talks about the temper he thinks he inherited from his father. But that never came out in public.

Yes, he had a big temper that he very much worked on consciously to control, especially in his public life. Not to hide it from people, but to not be a person who used anger and bullying to achieve results. He was terribly angry at Governor Faubus about Little Rock; he was terribly angry at Joe McCarthy. But he didn’t ever let himself be seen showing that anger and that temper in public. That might have gotten headlines and have rallied some people around him: “Here’s a guy who’s mad and he’s out there kicking ass for us.” But Eisenhower very purposefully controlled his temper and his rage against people, and tried to fix things by being diplomatic, gentlemanly, and respectful.

There’s a line that jumped out at me later in the play where he’s talking about the heart of America and he says, “There are still a lot of places in that heart that can be very hard to reach, especially if it involves change.” I initially misread it to say there are a lot of places in his heart that can be very hard to reach. Do you think there’s some truth to that too—that he had that Midwestern reserve that tells a person to push their feelings down and not look at them?

I can’t say that I know. There’s a book by his granddaughter called How Ike Led—not a great title, but a really interesting book, and a lot of it’s in Richard’s play. She quotes and describes him a lot. It would seem to me, and this is a guess, that he was aware of his weaknesses and his strengths. He made deliberate choices what to show the public, but at home with his family, he was very much more himself. And they all saw him that way. I don’t think there were parts of himself that he didn’t know. He really understood his father. He really understood his mother. And he understood what he had gotten from them as a very young child. As a young man, he sort of analyzed himself. I don’t know—obviously, we all have parts of us that if we went to a shrink every day, we might say, “Oh my God, I never realized that.” I’m sure that was probably true of him too.

You know, in the 1940s his actual title was Supreme Allied Commander in the European Theater of Operations. When you have that kind of responsibility, I just think that you walk carefully—or you should, anyway, and he did. Plus, in the 1940s and ’50s people were sort of reserved; people didn’t let it all hang out like they started to more in the ’60s and ’70s. Or like Donald Trump, who goes out there and basically drops his pants in front of crowds of people—just totally bloviates on anything that happens to cross his mind. That was unheard of in those days.

I think it says a lot about him and his sense of himself that when he left office, rather than being addressed as president, as most ex-presidents are, he insisted on being called general.

Yes, his military education changed his life, as it probably does many people. He only joined the military so that he could get a free college education, because his family had no money—but once he was in there that informed his character a tremendous amount. And I think that having gone through all of the levels, the tiers, the ranks of the military, and once he was general, and a general who was given this tremendous responsibility, with so many people’s lives in his very hands—that to him was the apotheosis, the pinnacle. When he was elected president and had to deal with politicians and Congress, I think he took it extremely seriously and did the best he could, but being general remained the honor and the essence of him.

It’s funny, he neither sought military glory nor had any great ambition in politics, but in both cases felt called to live up to a responsibility he was handed. That feels like a quintessentially American story, but not the one we usually hear about dreamers and strivers, pioneers or con men. It’s more about an ordinary person called by circumstances to duty and decency, to do work no one else wants to do.

Because it’s not about him; it’s about the country. He sees the threat, and he says, “I have, by fate and hard work, found myself in this position where it seems to be me—I’m the one who is stuck having to solve this problem. If I don’t, the problem will not be solved, or it will go in this other direction. And that will not be bad for me but bad for the United States, so I’ve got to step up.”

The elephant in the room here, no pun intended, is how far we’ve come from that ethos, and specifically how far the Republican Party has strayed from Ike’s temperamental conservatism, not to mention his relatively statist politics. It’s a big question, but how do you think we got here?

Something was broken. You know, you break your leg and they’ll fix it, but you never walk the same again. And you will always have the pain at that place where all the metal and screws are in your bones. When Jack Kennedy was assassinated, something broke. I’m not saying that led to the kind of horrific politicians that we see now on a daily basis. But that was the end of the old era, and beginning of what, we didn’t know—there was no name for it. I still can’t come up with one right now. But the assassination of that young president—there was just something so compelling about Jack Kennedy and what looked like the next four to eight years of our lives, and then that was done. And there was Lyndon Johnson, who was almost the extreme opposite. And then the Vietnam War and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, that whole combination of events. They were obviously very different events, caused by different reasons. Then Nixon was president when it should have been Robert Kennedy, and he was a madman—not like Trump, Trump is beyond. But I remember those days with Nixon as president. He did some very good things, and today he would probably be a Democrat, but…

I’m not sure I’d go that far. But I think he would have hated Trump.

When you watched him on television, you could see him flash a smile that was completely unreal. He was scary. When Watergate happened—which, compared to what presidents have done since, Iran-Contra, Clinton and his bullshit, and certainly Trump, looks like a silly prank—it brought him down because there were the last vestiges, even in the Republican Party, of decency. Ever since then, the trust in our president has been sullied. I don’t know when it comes back. Obama brought it back for a lot of us. But he was the first Black man in the White House, and that uncorked the always simmering racism. So now the persecution of women with the abortion ruling, the persecution of homosexuals and transgender people, in state after state—all of that stems from the anger about having a Black man in the White House.

Thinking back on what you said earlier, about how you were looking for a one-person show and this one just showed up—I wouldn’t want to push the analogy too far, but it’s a little bit like how Ike didn’t seek out the specific problems and opportunities that came his way, but rose to the occasion when they did.

That’s one of the glories of an artistic career, and specifically of a theatrical one. You are hired to embody people: drug addicts, mass murderers, in my case a lot of doctors and lawyers. On Children of a Lesser God, I was introduced to the Deaf community and learned sign language. I’ve played a lot of Jewish roles, though I’m not Jewish; my mother was Catholic and my father was Jewish, but they both hated religion, so there was no religion in our house, and I’m so glad and proud of that. But because of my last name I’m often cast that way; I played a Jewish ACLU lawyer defending the First Amendment right of even the Nazis being free to speak their filth in Skokie. I’ve learned about so many things throughout my life here playing all these roles. But this Eisenhower one has really struck a big chord in me. And I’m excited to get out onstage and do it for the people every night. I just love it.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre.