Practice may be the way to get to Carnegie Hall, but the path to Broadway is less simply summed up. That’s true not only for actors and writers and stagehands but for nonprofit theatre companies as well, dozens of which have transferred promising plays and musicals to New York’s Tony-eligible commercial district since nearly the beginning of the regional theatre movement in the 1960s.

There are also now four nonprofit theatres with control of Broadway venues in New York City, and each arrived at this juncture via slightly different roads. In the case of Lincoln Center Theater, the Broadway designation came by fiat, essentially, with the Vivian Beaumont Theatre’s construction in 1965 as part of a palace of culture alongside the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic, while the most recent entry to this category, Second Stage, secured Broadway’s smallest house, the Helen Hayes, to host both curated rentals and some of their own programming as well.

Similarly but on a much bigger scale, Roundabout Theatre Company—whose leader since 1983, Todd Haimes, recently died—has over the decades expanded its purview beyond its Off-Broadway origins to fill three Broadway houses with a mix of rentals and core programming, alongside two Off-Broadway spaces. As Haimes told me when Roundabout was celebrating its 50th anniversary, he had had no master plan to build a nonprofit theatre empire but simply saw and seized opportunities for growth as they arose.

Lynne Meadow and Barry Grove, artistic director and managing director of Manhattan Theatre Club, respectively, likewise had no master plan in the mid-’70s when they began running an Off-Off-Broadway company on a few floors of the Bohemian Benevolent and Literary Association on 73rd Street. But, as they told me in a recent interview, their ambitions for growth followed those of the writers they produced, who craved, deserved, and earned a bigger platform. Accordingly MTC grew through the ’80s and ’90s into an essential New York institution, first with one, then two venues at City Center in Midtown Manhattan, and eventually its own Broadway house, the Samuel J. Friedman, on the site of the Biltmore Theatre in the theatre district. Across these various venues, MTC became synonymous with brand-name American playwrights of a certain generation (Shanley, Henley, McNally, Margulies, Greenberg), but the theatre’s commitment to new writers hasn’t waned in the years since the glory years of Doubt and Proof. Even as Roundabout and Lincoln Center have gotten into the new-play game, MTC’s various theatres have since hosted major works by Lynn Nottage, Qui Nguyen, Tarell Alvin McCraney, Martyna Majok, and many others. And until Second Stage ventured onto the Main Stem, MTC was for many years the Broadway nonprofit most likely to stage plays by living American (and occasionally English) playwrights.

MTC stands out for another reason: It has been run for nearly 50 years by that same leadership team. Grove, who came on in 1975, is stepping down this season, while Meadow, who was hired in 1973 as the theatre’s first artistic director, is staying on past her 50th year at the helm. While Meadow said at one point in our interview that she can’t quite imagine “life after B.G.,” she shows few signs of slowing down. Our conversation in March ranged freely over the history of the theatre and could have gone on for days. The following is as compressed a version as I could manage. For those, like me, who are fascinated by the incestuously entwined history of nonprofit and commercial theatres—a sometimes awkward but inarguably fruitful marriage, which has given rise so much of both the theatrical canon and the industry landscape we now take for granted—there’s a lot to chew on here.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: I want to start by asking how well you’re doing in terms of audiences. It’s on everyone’s mind now since theatres have fully reopened; a few weeks ago Charlotte St. Martin said that Broadway audiences are back to about 88 percent of capacity compared to pre-pandemic. Does that sound about right?

BARRY GROVE: The Broadway numbers are up because they have some robust musicals going. There are seats available for locals to buy that haven’t been available for a long time because they weren’t pre-sold. And in the fall through to the beginning of January, there were a bunch of plays on Broadway, including some star revivals—Piano Lesson, Death of a Salesman, Topdog/Underdog—and those plays had stars in them, had high recognition factors, and seemingly grossed a good bit of money. But the capitalization for those shows is four times what it was when we moved, say, Lynne’s production of The Allergist’s Wife or Proof or Doubt, pieces like that. Those capitalizations are very large now, and they have closed many of them at a loss. So how much of the audience is fully back for playgoing? For new-play-going? And how much is back Off-Broadway? As we look at the national numbers in the nonprofit sector, the same thing is true. Which isn’t to say that it isn’t robust artistically; it’s that people aren’t working full-time at their desks in Manhattan, they’re up in Westchester, in Westport, out on Long Island, and aren’t necessarily coming regularly into the city. Some of those folks are still very much afraid of COVID or have altered what their patterns are, just as they’ve done for moviegoing.

On the other hand, you know, we’ve had some terrific responses from the audiences. We just finished an amazing success with The Collaboration, with Paul Bettany and Jeremy Pope. We are doing robust pre-sales with Laura Linney and Jessica Hecht for Summer 1976. So I’m hopeful, but it’s a long way from being back to 88 percent in the nonprofit world, I would say.

Another trend we’re seeing is the decline of subscriptions. One way to ask this is, you’ve got “club” in your theatre’s name, and that connotes membership. How have you been faring on that front?

LYNNE MEADOW: About the name: Our first board chairman named it Manhattan Theatre Club because he was a correspondent for The Wall Street Journal in London, and he attended theatre at the Arts Theatre Club of London, which was a private club and therefore not subject to censorship by the Lord Chamberlain. PBS is doing a feature on us coming up this fall, and we found the first brochure I created for MTC—this is pre-Barry Grove—and it’s a picture from a production of Little Mahagonny and it says, “Join the least exclusive club in town.” I hated the title; I told the board, “I want to change that,” and they told me I couldn’t, so we kept it. But we like to think of it, not only as the least exclusive club in town, but also as a club for every artist and every person who loves the theatre—a club for the entire world.

BARRY: At the beginning, membership was the backbone of MTC, and at most of American nonprofit theatres; Danny Newman at the Lyric Opera of Chicago was like the Johnny Appleseed of the subscription model. Lynne and I went to the very first TCG conference on the Yale campus, and Danny was there. By then Lynne had already formed a membership, but the subscription really came with help from Danny and one of our board members, who was from American Express, and whose advertising agency, Ogilvy & Mather, took us on pro bono. So we started working on building subscription.

For a long time, subscription really was critical; 80 percent of the audience were subscribers. But as time has gone on, people’s habits have changed. Those numbers have reduced; people want flex passes more than what used to be called fixed-night, fixed-seat-location packages, and they want to pick and choose which shows they want to come to. They’re still a strong part of who we are, but like most theatres now, I think the majority of the audience are single-ticket buyers.

LYNNE: The other thing I would say is that when I started at MTC 50 years ago, I was interested in doing new work. I didn’t want to be bound by audiences having to recognize the name of a playwright. So the idea I started with, with which Barry ran, was the idea that you would come because something interesting was going on there. It’s really built into the fabric of MTC, and in a way continues to some extent. Last night we opened a play by a first-time playwright, Emily Feldman; no one knows her name. It has been our hope and our continued dedication, thanks to the incredible support of our board and to Barry’s creating an infrastructure, that there is a place that has a sizable reputation for supporting the work of new playwrights. So it’s part our story: trying to staying committed to the values that we started with, while being realistic about what’s actually practical now. Certainly the challenges have changed.

I want to go back to the beginning and ask about theatre in the early ’70s. The Off-Broadway scene as we think of it was really only about 10 years old by then; meanwhile there was a lot of experimental work happening Off-Off-Broadway. Is that part of the world you came from, Lynne?

LYNNE: Definitely. When I arrived in New York, I was on a leave of absence from the Yale School of Drama, where I was a directing student; I had done two years. I left and went to Paris, and worked for a short time with Jean-Louis Barrault, created my own international company that did some touring, performed in Paris and did some touring around France. I came back to finish my third year at the drama school and decided instead, with advice from an important mentor of mine, Nikos Psacharopoulos, who I had worked with at the Williamstown Theatre, that I just go directly to New York. When I arrived in New York in ’72, there was this thing called Off-Broadway that I knew only little about—people like Marshall Mason, who had started Circle Repertory Theater, and Bob Moss, who had a place called Playwrights Horizons at a YMCA on Eighth Avenue, were doing work that interested me. There were theatres spread out all over town. I knocked on doors and met people and I was offered stage management jobs—I’m sure my partner of these many years would have to laugh at the idea that somebody would choose me as a stage manager; I’m not cut out to be a stage manager!

I learned about a place called the Manhattan Theatre Club, which had been created by a group of businessmen in 1970. They had actually offered the executive artistic directorship to Nikos, my mentor. They were only renting out space, they weren’t really producing anything, so I had a play that a friend of mine from the drama school at Yale, Anthony Scully, had written that I wanted to direct, and I went to MTC to rent a space. I raised some money from the New York State Council on the Arts, and we did some publicity and sent out cards. I didn’t realize that I was not just directing the play, I was making the whole thing happen—or producing!

During the run of my show, I was tapped by a man named Gerald Freund, who was head of a search committee for the board, to recommend a new leader for the company; they were looking for a new executive artistic director. I had landed a job in the cheese department at Zabar’s, which I was very excited about, but when this job came up in July 1972, after much deliberation, I decided to take it and go to the Manhattan Theatre Club. I was given only a three-month contract at first—they had little faith in a 24-year-old woman director. They renewed my contract after three months, and I’ve never had another one in five decades.

Early on, I knew that I wanted to do new work by new writers. The other thing I knew is that I had to find somebody who had the kind of commitment and passion that I did about the theatre, and someone who could handle the business side in a way that I handled the artistic side of the theatre. A couple of years later, I found Barry Grove and asked him to join me. He said yes, and then he changed his mind and said no. A year later I went back to him and asked him if he was ready now, and he accepted my offer. And here we are.

Why did you say no at first, Barry, and what persuaded you to finally say yes?

BARRY: I said no because it wasn’t right for me and my family. We did something nobody does anymore, which is, got married right out of college. My wife and I met at the O’Neill. Lloyd Richards was the artistic director and his assistant was a woman named Maggie Blackmon, and that’s how we met. She’d moved with me to Rhode Island, and we were just sort of settled and starting a life. To be there only one year and pull up stakes and go back to New York—it was for personal reasons I said no. But a year later, we’d had two years there and settled in, and I began to realize that if I was going to work seriously in the theatre, I needed to go to one of the big cities, not be at a university. So I met Lynne for real the second time, and we decided to come together.

LYNNE: I went back to you because it just seemed completely right that you should do that job.

BARRY: By the way, it wasn’t an Off-Broadway theatre then, it was an Off-Off-Broadway theatre, and there was a bright line between those two things. An Off-Broadway strike well before I was there had gone to an arbitrator who ruled in the union’s favor; I don’t pass judgment on that, but it upped substantially what the Off-Broadway salaries were, and so a lot of theatres just couldn’t function in the Off-Broadway world, and that created a vacuum for theatres with 99 seats or less. Off-Off-Broadway had a showcase code that only allowed you to do 12 performances over three weekends, 99 seats and a maximum ticket price—drumroll, please—of $2.50. That’s a maximum potential gross of $3,000 for the run.

I watched Lynne direct a revival of Golden Boy with a young actor named Jerry Zaks, before he was a director. I watched the work they had put in, and it was absolutely no different from what I experienced when I’d worked as a young assistant to a director on Broadway. So I went and asked Equity for an extension, and they turned us down. Later, we did a revival of Athol Fugard’s Blood Knot with the late Robbie Christian and a man named David Leary, who was a friend of Don Grody, then the head of Equity. Don came to see the show, and I got to talk to him live, as opposed to just kind of appealing blindly, and he said yes. So we got our first extension to be able to add a week to that show, and over time, we were able to kind of grow our way into Off-Broadway. Also, Lynne had a relationship with Richard Maltby. Maybe you tell this part of the story.

LYNNE: I love a three-ring circus, so I always had things going on in lots of different rooms in the space on 73rd Street. We occupied three floors of a five-story building, the Bohemian Benevolent Society. In my first season at MTC, there was a group of writers who were part of something called the New York Theatre Strategy; it was Sam Shepard and Lanford Wilson and Terrence McNally and Julia Bovasso and Irene Fornes, and they were all upset because no one would do their work Off-Broadway. So they said, “Will you co-produce with us? We want to do a seven-week festival of 23 plays.” I said, “That sounds great.” I was dying to meet and work with all those artists; I had read their work and I was a great fan. So with no technical director and a full-time staff of two we produced this festival, and it went on in every room in the place. So, you know, Terrence McNally’s Bad Habits started in Room 10. Anyway, there was always a lot of activity.

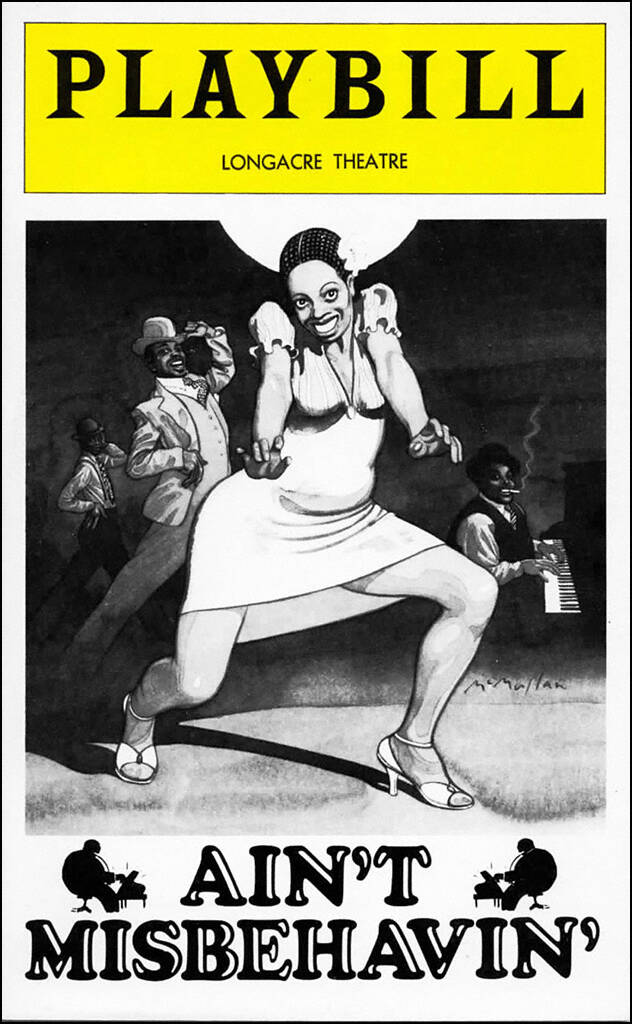

We had a 150-seat proscenium theatre, but at first we only used it a couple times a year; the rest of the time we rented the space to pay our rent and to pay a minimal staff. But then we had a 60-seat cabaret where we did musical evenings, tributes to various composers. Remember Meat Loaf, the singer? He’d come over with Donnie Scardino and Victor Garber and they would sing in the cabaret. And in 1977, Richard Maltby, who had put together some galas for us, was directing a show and it didn’t go so well. I had an opening for February in the cabaret, and I said to him, “Why don’t you do one of these musical tributes for me?” He said, “I’m feeling a little down in the dumps.” I said, “Remember that Fats Waller idea you told me about? Why don’t we do that?” So we did this five-person show on a tiny stage, it was a postage stamp. We did it at MTC, and then we moved it down to the Public Theater. That was Ain’t Misbehavin’. When it went to Broadway, we were granted a tiny percentage of the show going forward, which meant there was a little bit of money in the coffers to pay people.

BARRY: That generated some money, and that helped in two ways. With a lot of these early showcases, you’re just reimbursing people for expenses. We wanted to get to a place in that 150-seat theatre where we could be on a proper Off-Broadway contract; I think in those days, it was like $175 a week or something. We couldn’t do that with all three theatres at once, but we were able to spend part of the money doing that and put part of the money away for a rainy day. Thank God we did, because, jump ahead to 1980 and the Bohemian Benevolent and Literary Association decides they want to sell the building; they wouldn’t renew our lease, but they would sell us the buildings, plural, if we had the money. It was $1.6 million they wanted, and there was no way in hell that we were going to be in a position to do that. But we had a wonderful new board member named Ed Cohen, and he also knew an incredibly talented and generous real estate lawyer named Charles Goldstein. They took me by the hand downtown, and ultimately we convinced the city to put up the million six to buy the spaces for us. Okay. But as we were negotiating the contract, it turns out the Bohemian Benevolent Society was not one thing but a group of 10 different associations—it was a historic shrine to some of the leaders of the Czech community during World War II, and they didn’t want to see it go away, so they sued to stop the sale. They went through three years of different layers of the court, because we had a valid case. On the other hand, they weren’t a commercial entity; they were another nonprofit with a cause. Ultimately, they were able to prevail and say, we’re going to keep this space; we want to restore it as a Czech entity. It’s now the Czech consulate to the United Nations.

So we had six months to move. Lynne and I went looking everywhere for spaces. I went to see Gerry Schoenfeld at the Shuberts and he said, “Why don’t you look at that space under City Center?” So we tried there, but it needed real money to be fixed up. We put half of that Ain’t Misbehavin’ money in the bank, and we had friends from our early fledgling board, Exxon and the Schuberts and a couple of others came and pitched in, and we were able to successfully transition over to City Center with a 300-seat space that was going to be fully Off-Broadway.

LYNNE: Can we just go back for a minute? What we haven’t talked about is the artists who were working at Manhattan Theatre Club in the first 10 years. I’m not sure we have a production history, but I think it’s important though to note where I made commitments and who were some of the artists—I just jotted down some of the names, in no particular order: We did Beth Henley’s Crimes of the Heart, Donald Margulies’s plays, Mass Appeal by Bill Davis, a number of works by Athol Fugard, Ed Bullins, Pete Gurney. Terrence McNally’s play Bad Habits transferred; Richard Wesley’s play starring a young actor named Morgan Freeman, called The Mighty Gents, transferred to Broadway. We did a play called Talking With with Margo Martindale; Holly Hunter did Beth’s plays for us; Christine Baranski and Bernadette Peters did a play called Sally and Marsha. I was just looking through this document we have, you know, with some of the years—these are just off the top of my head, but I think within the first 10 years, there were so many writers who came to MTC and did work in our spaces that by the time we left for City Center, we were producing full time. We also did a number of English playwrights; we were probably one of the first companies to do that. David Rudkin, who wrote Ashes; the works of Stephen Poliakoff, Howard Brenton, Brian Friel. What I think was so key about the first 10 years, just from an artistic point of view, is that I cast a very wide net.

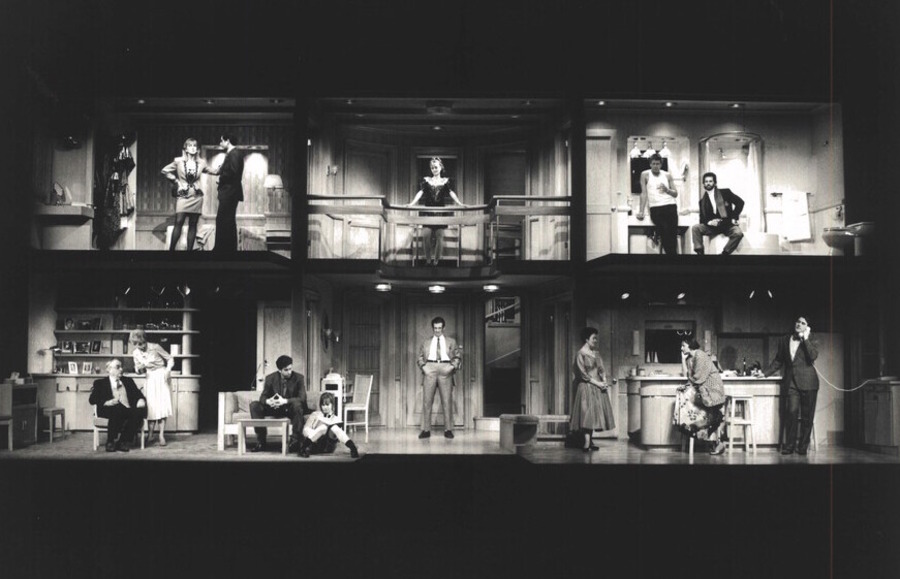

When we moved to City Center, I focused on a group of writers whose work we have done for decades now—always keeping an open door, and to this day we pride ourselves on that—but there were people whose work we had produced, and to whom I made sustained commitments. So we did 12 of John Shanley’s plays, 14 works by Terrence McNally, six by Beth Henley, five by David Lindsay-Abaire, four by David Auburn, many by Richard Greenberg. That was in our second 10 years, at City Center. But we had only one theatre there, which made me anxious. Doing one thing at a time has not been my favorite thing; I like to pay attention to a few things at once. So after our first year there, we created a second theatre, a 150-seat thrust theatre. It was the first place we did David Lindsay-Abaire’s work and Tarell Alvin McCraney’s play Choir Boy and Sight Unseen by Donald Margulies and The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife by Charles Busch and Heisenberg by Simon Stephens. I know I’m jumping ahead, but those became a launching pad both for shows moving to Broadway, and then producing shows ourselves on Broadway. Once again, I’m jumping ahead to the real estate, which Barry has been so amazing at making happen, keeping us growing.

So now we create work in our theatres at City Center that moves to the Friedman Theatre on Broadway. There’s a clear trajectory of sustained commitments to artists, and also an equally strong conviction about launching talent. One of the things that makes us feel the most proud is the breadth of artists who’ve called MTC home, whether they’re Julie Andrews or Timothee Chalamet or Jeremy Pope. So that word “club” that I hated so much—it’s a club with wide open doors, and a place that people can call home and come back to.

This is a question I was curious about when I talked to Todd Haimes about how Roundabout went from a small Off-Broadway theatre to running three Broadway houses. He told me there wasn’t really a master plan behind that evolution. Was there a master plan at MTC, or did it just keep developing over the years?

LYNNE: Early on, I was interviewed by PBS and asked, “What do you want—what are you looking toward?” I said, “I’d like this to become a landmark in New York City.” I tip my hat to Barry’s constant vision of getting the work out to more people, of creating the spaces. I don’t think we ever said, “This is a plan.” But he saw my work and he said, “More people should see this.” It wasn’t an articulated plan. My vision was that I wanted to do excellent work. I was a director who could not get hired as a woman. But if I was going to work in a theatre, I wanted that theatre to have a first-rate reputation.

BARRY: It wasn’t linear in the sense of, Off-Off-Broadway to Off-Broadway to Broadway. In moving to City Center, we lost half of our audience, but because of the quality of the work, and because we were now located in Midtown, by the time we got to the end of that first season, we actually had a larger audience than when we were at 73rd Street. When we filled that up, we were able, with the help of the great board leadership, to renovate City Center and create a Stage II that would give Lynne more than one space to be in. Again, we began to fill up the seats and the place wanted to go somewhere else. Broadway wasn’t even remotely in the picture at this point early on, but we had a lot of commercial Broadway theatres out there that weren’t packed all the time. And Off-Broadway, there was the Promenade on the Upper West Side, the Lortel downtown, the Minetta Lane and the Variety Arts on the East Village, and some theatres on Theatre Row. We were able to start a kind of hopscotch approach to transferring shows from our own space to Off-Broadway commercial spaces, initially taken over by commercial Off-Broadway producers, then eventually by ourselves—we got a grant from the Wallace Foundation that was all about expanding audiences, and we were able to use it as a revolving loan fund to finance the transfer of plays from one theatre to another. So Sarah Jessica Parker was starring in Pete Gurney’s Sylvia with Chuck Kimbrough, and it stayed for a while at MTC, but instead of just doing the six- or eight-week run, we moved it over to the Houseman on 42nd Street. Lips Together, Teeth Apart, a piece that needed a swimming pool, stayed at City Center for a while, and then we were able to move it down to the Lortel. We did that over and over again, and we got to a place where we had three and four plays at a time running under MTC’s aegis. Because the costs were still relatively modest Off-Broadway, you could finance those transfers for $250,000 apiece. But with Lynne continuing to do all of the volume of work she was talking about with all those artists, we reached a point where some of those artists also wanted to go to Broadway.

LYNNE: The artists wanted longer runs, and they all deserved that. They’d say, “We worked so hard, we’d like more people to see it.”

BARRY: Terrence really wanted his next play to go to Broadway. There was something called the Broadway Alliance that Robert Whitehead and a couple of others had formed that allowed you to go into what were literally at that point called endangered theatres—the small theatres on Broadway, because this was the time of the big musicals: Cats, Phantom, Les Miz. So you got a discount if you did that. We were able to convince Rocco Landesman to give us $800,000 as a non-recourse loan and take Love! Valour! Compassion! to Broadway.

Lynne wanted to do a play called A Small Family Business by Alan Ayckbourn. Alan had his own small theatre at Scarborough, so pretty much anything he did at his theatre you could do at City Center. But then he got commissioned by the National Theatre to do plays at the Olivier, their biggest space. One of them was A Small Family Business; it required a two-story simulcast set going on at the same time. So we were able, with the help of our attorneys, to create a wholly owned for-profit subsidiary called MTCP, for Manhattan Theatre Club Productions, and together with some folks we were able to finance a $1.6 million transfer—but it really wasn’t a transfer, it was from the jump at the Music Box, a production that Lynne directed there.

In the meantime, you know, we were running out of room at City Center, because we kept expanding as far as we could go. Ben Mordecai, who was working with Lloyd Richards and August Wilson, wanted to do Fences, so they went to the provost at Yale and said, “Can we do this?” And the provost said, “You can, but only if you can guarantee me you can repay the money.” Of course, in the commercial theatre, that doesn’t really work. Ben and I knew each other already from the nonprofit world, so he said, “What if we get the Manhattan Theatre Club to bring its whole audience to the play? Then I can go back to the provost and say, ‘It’s not a guarantee, but we’re going to bring 18,000 people,’” and then he would be able to persuade them. In the meantime, we could take the other four plays that were in Stage I and expand them out longer in their runs. We did that, and it was a successful collaboration. It allowed our audience to be there, and it was one of the biggest group sales in Shubert history, and it anchored things for them. And we went on to do that also with King Hedley and Seven Guitars. By then it became really clear that we needed our own Broadway space.

I want to ask about your long time together. Can you talk about how you’ve worked together, and tell me the secret to your partnership lasting so long?

LYNNE: I wanted a partnership, and when I met Barry, I thought, This young man seems ambitious and passionate about the theatre. Those are the qualities I admire. My artistic policy was something I created when I came here and very clearly had very strong feelings about. The work on the stage is my vision; the policy of the Manhattan Theatre Club and who we are has been represented by both of us, and by our collaboration and our dealings with the board. Early on, we spent a lot of time talking to each other. And actually, as the years evolved, we spent less direct time talking to each other, because we knew a lot of what each other thought. We certainly don’t micromanage each other. It’s a collaboration, a partnership, and represents the support of an artistic vision that can’t happen without implementation and underpinning. There are delineated responsibilities and boundaries that we respect.

BARRY: I really only intended to be at the job for three or four years, and then to go somewhere else. If I had come into a fully formed, mature not-for-profit, that probably would have been true, because I would have been really bored. But there was always a new challenge and a way to expand the reach—to find great board members, to build a staff team that could do a lot of the things I used to do so I didn’t have to do them anymore. I spent a lot of time representing MTC in the community, first as the second ever president of the Off Off Broadway Alliance, then the second ever president of the Off Broadway League; I was a member of the board of governors of the Broadway League and the LORT League. I’ve been a trustee of Equity’s health and pension funds for 35 years, I’m on the Tony administration committee—not to brag, but to say that a chunk of my time is representing the institution in the community. I was the treasurer of TCG when Peter Zeisler was there. It was a way of both giving back to the community that fed us but also carrying the flag of the Manhattan Theatre Club out into the world as we were then trying to raise money, build partnerships, get commercial producers to bring their shows to our galas. I think of myself as a sort of prism. Lynne is laser-focused on the work, doing brilliant work, that then needs to be supported with an ever wider, ever taller, ever larger platform.

LYNNE: You’re forgetting, Barry, the commitment to teaching. In the early years, we both were eager to participate in the community. I was the head of the theatre panel for the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Council for the Arts. We’re going to bat for our colleagues in a way that people had gone to bat for us. I taught at Circle in the Square, I taught at Fordham, I taught up at Yale. And Barry’s had an amazing teaching career that he’ll tell you about; he’s trained so many people who are running theatres now. We’ve called our theatre a teaching hospital, to the extent that so many people who have come in and worked with us are now running theatres themselves. It’s legendary what he did up at Columbia. And as we’re now looking at trying to fill his enormous shoes, we’re looking at many of the people whom he has trained. And I also feel proud of the number of women who are out in leadership positions, running theatres, who have worked with me over the years.

I mean, I’m sure nobody would have guessed that my attention span would have lasted long enough to be here for 50 years. But as Barry says, things have always changed. The other night, we were at the opening of our show, and PBS was filming and it was all great, and at a certain point, someone said, “Can we talk to you and Barry?” So we went into the theatre and found out that an actor had come to the theatre on opening night who had gotten the COVID test and had COVID. It was clear that the show wasn’t going on, and there were 650 people out on the street who hadn’t been let in. And Barry and I looked at each other and said, “Just when we thought we had dealt with kind of every possible thing that can happen…” Barry, you should talk about your teaching.

BARRY: I’ve been on the faculty at Columbia for almost 30 years now. I started teaching right out of school. I was on the faculty at the University of Rhode Island. When I came to New York, I didn’t do anything right away because this was way too overwhelming. But relatively soon, I started teaching at Marymount Manhattan College, around the corner from our 73rd Street space. One of my mentors was a man named Peter Smith, who had been the artistic director at Dartmouth when I was there. He had been named dean of the School of the Arts at Columbia, and he reached out and asked me to join the faculty there. So I was teaching two courses a year on critical issues in the arts, on non-traditional casting, moving shows, rights for artists—whatever the issues of the day that we were looking at together with some very savvy graduate school students.

In the spring semester, I was teaching a course in development, and I didn’t want to just go in and talk to managers about this. I wanted the partnerships that make this work, like the one that Lynne and I have, because you can’t just set a course of action to fundraise; you have to take what the artistic director wants to do. I guess I came to the point of realizing that my job was not saying yes or no; my job was saying yes or “not yet.” Not yet means, I gotta go find some more money; give me a few minutes and I’ll get back to you. So we created a program where the literary managers program and the theatre management program at Columbia joined together and formed partnerships like ours—created an imaginary theatre and an imaginary season, budgeted it and figured out how they’re going to pay for it. For the final, I brought in some of the biggest fundraisers from the institutions in the city to hear the students’ proposals and presentations. It went well, and then Yale got wind of it and asked me if I would do it up there too, because my house is close to New Haven. I didn’t have the time to do it alone, but I asked if we could team-teach it out of the MTC staff, so that’s what we did.

Final question for Lynne, since you’re sticking with MTC for the foreseeable future. What are the challenges that still keep you up at night?

LYNNE: Right now, it’s hard to look beyond this moment of coming out of this pandemic. As we have lived through and are continuing to live through a pandemic, we’ve also had a revolution and are facing the exciting challenges of how we meet this moment, and all of the hopes and dreams and positive aspects of opening our doors with full inclusivity and wanting to meet our highest goals. It’s a challenging time; it’s a time full of aspiration, a time full of trepidation. We are living in extreme times, where some of the things that we hear on the news, I can’t believe. We are living in tempestuous weather. So being alive and conscious in this moment is demanding the most of our humanity and our intelligence, and our desire to create positive things in society. I guess that keeps me up at night. In some ways, I haven’t really slept in 50 years.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre.