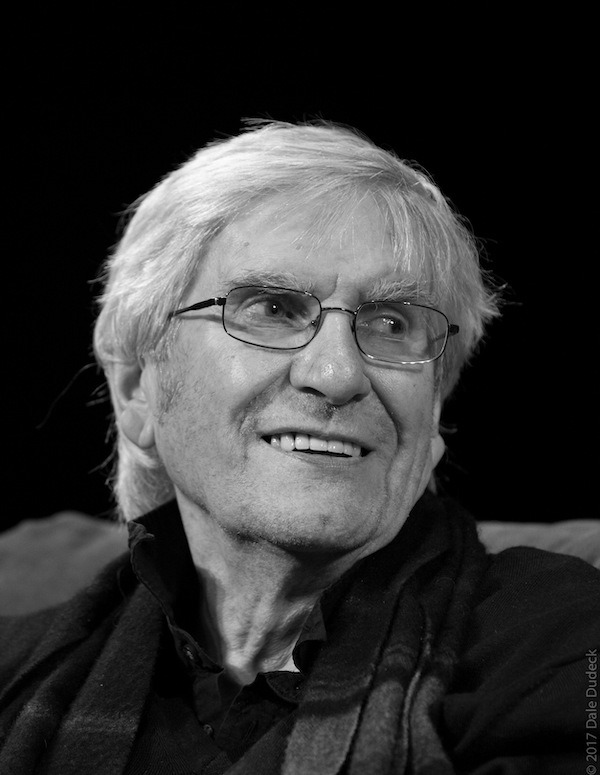

Keith Johnstone, a pioneer of contemporary improvisational theatre, died on March 11. He was 90.

When Keith died, a torrent of gratitude, grief, and personal stories poured in from every corner of the world. Tributes came from students, colleagues, teachers, and ordinary theatre lovers, in many languages, on social media, on blogs, and in handwritten tributes. Recurring sentiments included phrases like “beloved mentor,” “absolute genius,” “created space for magic to happen,” “a legend,” “unorthodox,” “the teacher who changed/saved my life.”

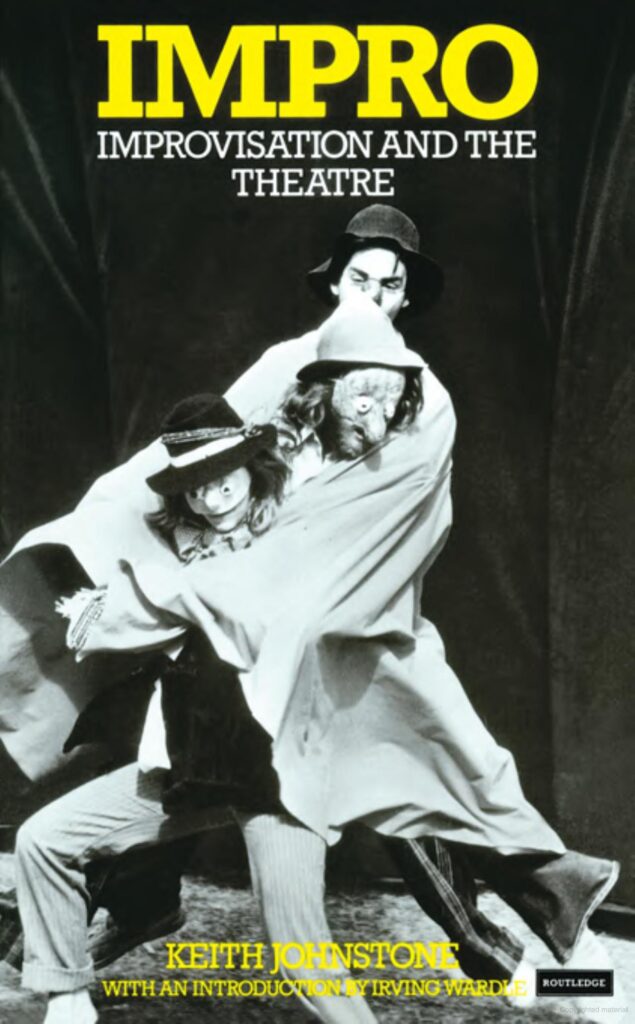

Gratitude came from people who hadn’t studied with Keith but had connected deeply with the theories and techniques laid out in his book, Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre (1979). Translated into more than a dozen languages, it continues to serve as a guide for anyone wanting to rediscover their imaginative potential and bring more creative spontaneity and authenticity into their work and lives.

To say that Keith made a difference is an understatement. Maybe that’s why I am sitting here, in the wee hours of the morning, struggling over what to write. Then I hear his voice in my head, in that lovely, warm British dialect, saying, “Be obvious.” “Please, don’t do your best.” “Be average.” “Screw up and look happy.” “What comes next?” These statements, which sound so simple, have freed the imaginations of creators from all walks of life. They eliminate the need to get it right and serve as a reminder to just tell the story.

Keith was born in Brixham, England, in 1933. He had a difficult childhood at home and in school. At an early age, he taught himself to read with comic books. Although he had a high IQ, painted, played piano, wrote stories, and was curious about everything, he always ended up at the bottom of the class. He had trouble with rote memorization and with an educational system that favored intellect over imagination, end results over process. During his teens, Keith became increasingly self-conscious and retreated into the subjects, books, and films that interested him. Essentially, he was self-educating and preparing himself for his life’s journey: to rediscover the imaginative potential of students, like himself, who had been oppressed by their education. Developing spontaneity was his goal; improvisation became his tool.

In 1951 Keith entered a teacher training college and his first full-time teaching assignment in Battersea introduced him to a class of interesting, curious children labeled by others as “ineducable,” reinforcing further his idea that “learning should be play not work” and “you can teach anything if it’s a game.” But it was his 10-year stint at the Royal Court Theatre (1956-1966) in London that gave Keith the learning environment he longed for, the laboratory to investigate the nature of spontaneous creation.

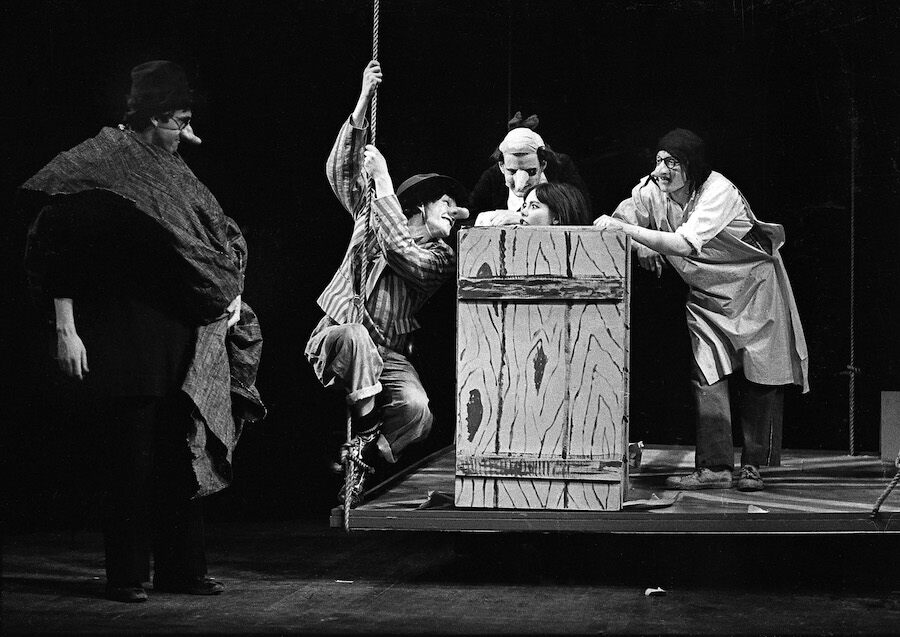

He entered the Court as an unknown writer but became head of the entire script department, a bold director, an influential member of the famous Writers’ Group, the Court’s expert on Samuel Beckett (who was also a friend and mentor), and head of the RCT Studio for professional actors. It was there that Keith began developing his impro system, often consulting his “Things My Teachers Stopped Me From Doing” list for inspiration. In the Studio’s short existence (1963-1966), Keith taught classes in narrative skills, spontaneity, status, character masks, comedy, and clowning to a generation of actors. The goal was to provide a space for actors to play, to try strange things, to recreate authentic human behavior, and to develop engaging stories through improvisation.

In search of a popular theatre with great audience rapport, Keith had to take the improvisation to the public. He called the performances “demonstrations” or “classes” because, until the Theatres Act of 1968, performing impro in public was illegal in Britain, since all scripts had to be approved by the Lord Chamberlain. Indeed, in 1965 Keith’s partly improvised children’s show Clowning, directed by William Gaskill, was given a license for performance, marking the first time improvisation was officially sanctioned on the British stage!

The four actors Keith used most often in his “demos”—Ben Benison, Roddy Maude-Roxby, Richard Morgan, and Tony Trent—would eventually become The Theatre Machine, Britain’s first improvisational troupe. With Keith serving as emcee and onstage director, this “pride of improviser lions,” as he called them, toured throughout Europe from 1968 to 1971, with fans following them from venue to venue to witness these players, adept at clowning, mime, and physical comedy, leap fearlessly over the abyss.

During this same period, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA) hired Keith to shake things up. A young Jonathan Pryce was a student in Keith’s impro classes there, and later, in a 2018 interview with me, credited Johnstone as “the man who released any inhibitions I may have had.” More invitations to teach and direct began pouring in from international theatres and major actor training programs. For the next 40 years, Keith would spend three to six months a year working abroad.

In 1972 Keith left London for Canada and spent two decades teaching at the University of Calgary, an institution like the ones that denied him entry as a young man. In the beginning, the university served as a laboratory where Keith could continue to investigate and develop impro.

But in 1978, Keith pushed the theatre department to its limits with Live Snakes and Ladders. Inspired by BBC radio game broadcasts, Keith imagined a sporting event with real snakes and humans competing in a greedy, brutal social system that no one dares to criticize. In his unconventional approach to making theatre, Keith wrote and revised the script during rehearsals, directing and collaborating with his 50-student cast, using impro as his tool. It was a “technical masterpiece,” according to theatre critic Louis B. Hobson. The theatre faculty, however, dismissed it as “a glorious failure.” His cast of students, many of whom were members of Loose Moose, the theatre company Keith co-founded the year before, disagreed. This would be the last production Loose Moose would co-produce with the department. A loss for the university, but not for Keith.

The Loose Moose Theatre had its first official performance in 1977, and over the next decade was a theatrical force in Calgary, with seasons of purely improvised shows, scripted plays (many written by Keith), and Theatresports, the popular theatre format (and now global franchise) that inspired shows like Whose Line Is It Anyway?. The Audience Team was one of the most popular in-house teams, and included Mark McKinney and Bruce McCullough (Kids in the Hall) and Norm Hiscock, who would go on to write for Kids in the Hall, Parks and Recreation, and King of the Hill. Keith served as artistic director of the Moose for 21 years, training and inspiring another generation of theatre- and filmmakers, educators, and beyond. Keith continued to teach workshops at the Moose and internationally up until 2018.

My surprising journey into the world of Keith began in 2001 when a close friend handed me a copy of Impro and said that if I liked Viola Spolin, which I did, I would love Johnstone. She was right. I devoured it. I felt as if Keith were talking directly to me.

In graduate school, I made impro and Johnstone my area of focus. For six years, supported by university funds, I followed Keith around the world, studied with him, observed him teach and masterfully unleash the imaginations of hundreds of students, combed through his personal archive, and spent countless hours in conversation with him.

Soon after my second impro workshop with Keith in 2008, my conversations with him really commenced, and over time got deeper, more familiar. Keith trusted me; he knew I wanted to get his story right, that I cared deeply about his work and its impact in theatre and beyond. He asked me to serve as his literary executor in 2012, and my first assignment was to place his archive at Stanford Libraries.

In 2013 my book Keith Johnstone: A Critical Biography (Bloomsbury) was published, and I felt I had earned a second doctorate in Johnstonian Studies. I watched dozens of films that inspired Keith, including most of Charlie Chaplin’s and Buster Keaton’s. My bookcases are filled with books Keith recommended. My favorite is Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, a selection of autobiographical stories from Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman—stories that reveal Feynman’s curiosity, common sense, and how important “play” was in his life, work, and education. Keith loved reading about science, but it was Feynman’s sense of play that resonated the most.

In 2017, my sister, cinematographer Alicia Robbins, and I started filming a docuseries called On Keith: Artists Speak on Johnstone and Impro. Our first project took place at the Royal Court Theatre, where we arranged a Theatre Machine reunion. I pinched myself as I stood on the stage where it all began, and directed the shoot.

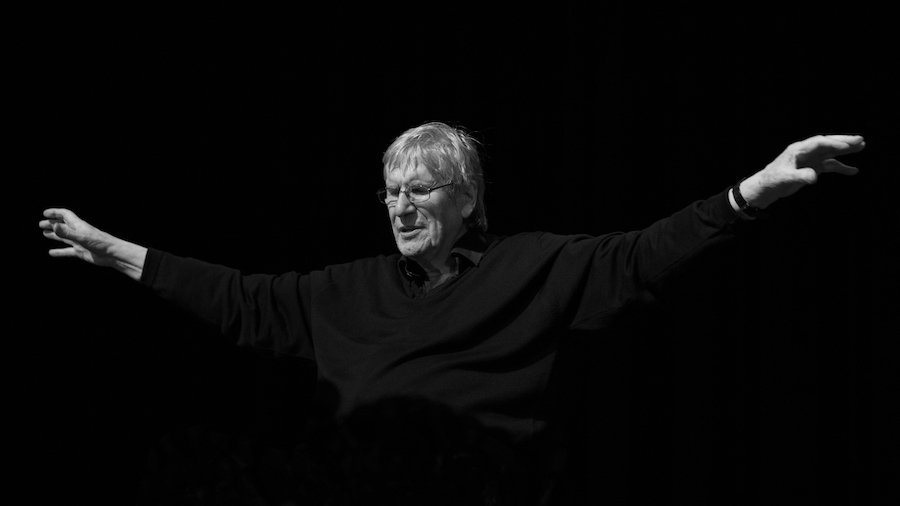

Keith, surrounded on either side by two of the original “lions”—Roddy and Tony—and Petra Markham and Lucy Fleming, actors often invited to perform as guests with Theatre Machine, discussed the old days and did a little spontaneous impro for an invited audience of artists whose lives Keith had influenced. Keith felt the evening was a disaster, especially the bits of impro he directed—or at least that’s what he told me. He told others the evening meant a great deal to him and, for those who watched it unfold, it was pure magic. The great intelligent beast, as Keith would call an audience, had been tickled!

The pandemic was hard on Keith. Isolated like so many, he wrote every day and read as much as possible. But he really missed teaching. I made every effort to call regularly. Sometimes we’d talk about impro, especially if I had a pedagogical question, but mostly we’d discuss other topics—literature, pop culture, classical music, politics, history, what Rachel Maddow had talked about the night before. For someone who had trouble memorizing anything his entire life, even a piece of music, Keith’s cognition was remarkable until the very end. I learned something new in every conversation. Keith was still my teacher. I was still his student.

My last in-person visit with Keith was just after Christmas. I flew to Calgary to be by his side after he was admitted to the hospital. Keith found himself in a situation he had always dreaded: hooked up to tubes, dependent on others.

When I asked him how he felt being there, he didn’t complain. He didn’t like being a pin cushion, hated the pain, but put the blame on himself. “I’m a terrible coward,” he said. Then he would praise the nurses who inflicted the pain. “They mean so well; they’re such nice people.”

As Keith said so often, a person’s true nature doesn’t change just because the circumstances do. Keith was still Keith: the keen observer of behavior, the humble genius, the English gentleman, and the droll teacher who would lower his status to put students at ease and establish trust, necessities for spontaneous, collaborative creation.

On the night Keith died, before it was officially announced, I emailed a handful of his closest students who have been conduits of his work over many decades. We began our grieving together, but also, almost straightaway, we felt Keith’s presence everywhere, guiding our classes, inspiring our teaching, filling students with wonder, in our dreams and meditations. Keith’s spirit was free, no longer earthbound and burdened, perhaps giving headaches to bad improvisers, as he said he would do. Or telling greedy people that true happiness comes from doing nice things for others. Or proposing these questions to a student wondering if her work was good: Were you altered? Did you release your partner’s imagination? Did you take the audience on an adventure?

Phelim McDermott, co-artistic director of the award-winning company Improbable, responded to my email with this: “I was thinking of Keith all the way through the opening of our Philip Glass’s Akhnaten opera last night…Mark Ravenhill was there and we spoke of him. The first scene is a ritual where Amenhotep’s heart is weighed on scales against a feather. It has to weigh the same in order to pass into the next life, and Keith’s wonderful heart weighed as such. Once into the next life the Egyptians believed the great Pharaoh was not somewhere else but still here in a parallel world. This is now true for Keith as far as I am concerned. He is with us all still, close.”

Yes. And…thank you for the adventure, dear teacher. What comes next?

Theresa Robbins Dudeck, Ph.D., is a theatre practitioner-scholar specializing in improvisation. She is the author of Keith Johnstone: A Critical Biography, co-editor of The Applied Improvisation Mindset, co-director of the docuseries On Keith, and Johnstone’s literary executor. Based in Portland, Ore., she teaches at Portland State and the Actors Conservatory.