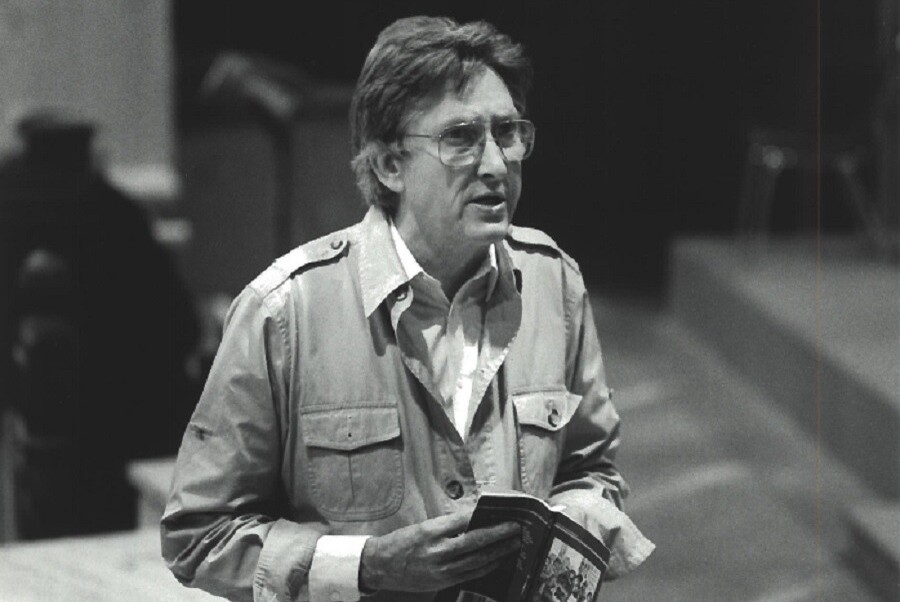

In 1997, the writer James Reston Jr. worked on a teleplay about Galileo with Adrian Hall, the director who founded Trinity Repertory Company in Providence, R.I., more than three decades before, and who for part of the 1980s also ran Dallas Theater Center in his native Texas. When Hall died on Feb. 4 at the age of 95, Reston offered American Theatre this remembrance of working with Hall, both on this never-to-be-produced Galileo teleplay and on Trinity Rep’s production of Reston’s 1983 play, Jonestown Express.

There is nothing intrinsically nasty about the verbs “to comb” or “to confuse.” So why did I shudder every time I heard them in the past eight weeks? In that time Adrian and I worked together for several hours nearly every working day. It was not quite the same as it had been 14 years ago when we fought and laughed our way toward the production of Jonestown Express in Providence. Far from those intense sessions up there on Mount Hope, this time it was a long-distance collaboration, and perhaps that had its advantages. And it was television now rather than theatre, with a $2 million dollar budget and no guarantee of production. It was an act of pure speculation with high stakes and huge implications for us both. We were engaged in a long shot, the proverbial crapshoot where our fate lay ultimately in the hands of academics and television producers who might never have read a real play.

Generally, we worked in the early afternoon, since Adrian needed the morning to direct the hands on his Texas spread. These were his farm hands, not his stage hands, and I loved thinking about him as a Texas rancher as well as a play doctor. He was in the process of building his “performance barn” in the fire-ant field near “Hall Manor.” His barn was to be his way of bringing Trinity Rep to East Texas. But in the six weeks we worked on the phone he seemed more preoccupied with a gate and a bell tower for the barn. Bell tower? In Van, Texas? Since we were focused on the Renaissance, I began to refer to his belfry as Adrian’s campanile.

I would gather the old pages and the new pages of our script, arrange them in neat piles along with my legal pad, take a deep breath and dial his number down in Van Zandt County. As the country tones of his rural telephone rang on and on, I would arrange my view high in my tower in the Smithsonian castle (where I was a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center), just so the Washington Monument was perfectly framed in my Romanesque window. I knew Adrian and I would be chatting about God-knows-what for God-knows-how-long before we actually got to work. Often we talked of what he had seen on television the night before: Rhonda Fleming’s red hair, William Hurt’s makeup in the last scene of Jane Eyre, what the death of Princess Diana said about our sense of tragedy and illusion, how they were sticking it to that dirty ole child-abusing Dallas priest with a multi-million dollar punishment. I could scarcely fault him for watching so much television. The tube brought so many of his actors into the living room.

I loved these preliminaries with Adrian. They were endlessly entertaining, of course, but they were also important. By now, I knew very well how his mind worked, how it needed to crank itself up slowly, for his intuition and eventually his genius to kick in.

As the phone continued to ring, I could picture him in his nest. He would be standing over his stove, wrinkled and rumpled and probably coffee-stained in his kitchen, beneath those antique signs for soda pop or leaded gasoline which he had acquired at his beloved flea market over in Canton, where on the first Monday of every month they had a gigantic sale of treasures and unbelievable junk, worthy of Texas. He would know that was me on the line, because we always had a loose pre-arrangement.

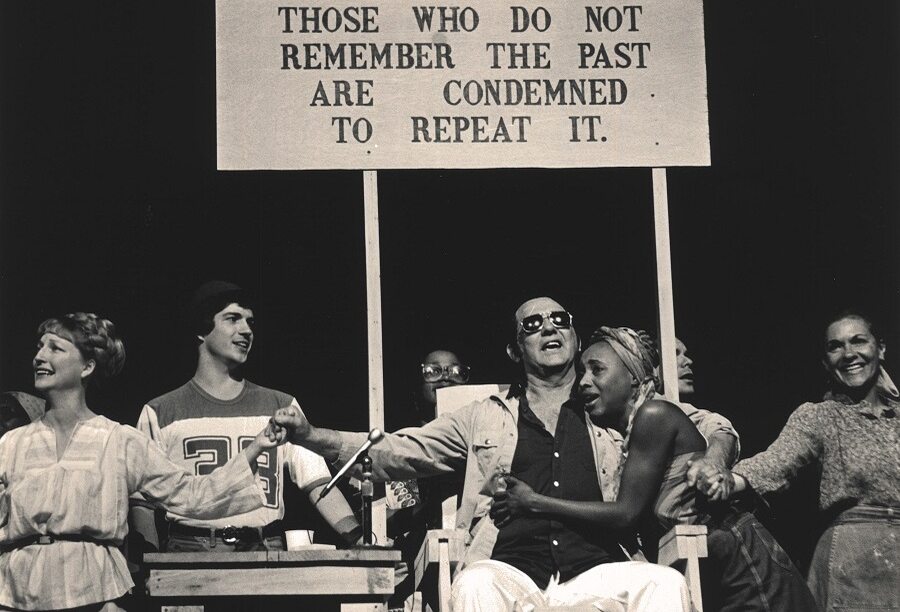

If he was in the kitchen, he would ask me to hold on and put the phone down. I could hear his hollow footsteps echoing down that ornate hallway, over-decorated with the props and posters of his favorite productions of the past 33 years, including his 1983 production of Brecht’s Galileo. Secretly, I was hurt that Jonestown Express, our 1984 play on Jonestown at Trinity Rep, was absent from his personal hall of fame, for I wanted to be high up there alongside Harold Pinter or Lillian Hellman, or, most of all, his mentor, Jerzy Grotowski. Instead, even the grotesque visage of Charles Manson beat me out. By contrast, in my study at home, the poster of Jonestown Express sits right over my computer in the most honorable of places, so that every morning when I go to work, I look into the faces of the cast: Richard Kneeland as the Rev. Jim Jones, Richard Kavanaugh as Jerry Joe Snipes, Barbara Meek as Millie, and Barbara Orson as Christine Miller. In that group shot of the cast, with their fading, cheery inscriptions along the border, they smile out at me broadly and impishly as Jonestown devotees beneath the headline: “We were 913 Americans with a joyful dream of Utopia!”

The play had received mixed reviews. Bill Gale of the Providence Journal hated it, and Mel Gussow of The New York Times patronized it. Those disappointments alone were not enough to bar its presence on Adrian’s wall, for Adrian had taught me a lot about having a tough hide. But Time magazine gave it a rave, carrying an eerie picture of Kneeland under that single red light bulb in the jungle, one of Adrian’s special directorial touches, and Theatre Communications Group published it as one of the 12 best new plays of 1984. Its poster has its hallowed place in my study because that work with Adrian represents the highest artistic experience of my writing life. For all other work I have a certain standard.

At last, Adrian picked up the phone in his study. There, surrounded by his theatrical library that only the most worthy institution in New England or Texas will someday receive and by the mementos of so many friendships, he was finally ready to get serious. Inevitably, he uttered those terrible, terrible words: “I’ve been combing through our work yesterday, and I’ve realized we’ve made some mistakes. Quite a few places still confuse me.” Here we go again. I kept my groan to myself.

This was our task. In 1991, when I began work on a biography of Galileo, I realized that within 20 volumes of Galileo’s letters and the actual transcript of the astronomer’s interrogation by the Inquisition in 1633—a document that only became available in 1984—there lay, somewhere, an entirely original, well-documented, modem drama about Galileo. It could be so much better than Brecht, I felt, devoid of his irrelevant political baggage, and exploiting new evidence about Galileo’s trial which Brecht had completely skated over. This raised the specter of a “docudrama,” that tainted form which has fallen into disrepute in the muddy fingers of Oliver Stone.

Moreover, three contemporary events made a new film about Galileo modern and timely. There was a space mission called Galileo that sent a satellite to Jupiter and thus was symbolic of the revolution in astrophysics that has taken place in the past 20 years. There was the reconsideration of the Galileo case by the Catholic Church, which led to the extraordinary act on Oct. 31, 1992, when Pope John Paul II formally apologized for the Church’s treatment of Galileo in 1633. And finally, the millennium approached. It was a time to teach and to reflect, and even television might raise its general level of discourse. As the year 2000 A.D. approached, the conceit of our play was the playwright’s belief that Galileo was “the man of the millennium.”

For years, I had longed to work with Adrian again, and I enlisted his help in this epic enterprise. After my time as an “artistic associate” at Trinity Rep, we had kept in touch. I had attended his Washington shows of The Taming of the Shrew and All the King’s Men, his Broadway premieres of The Hothouse and On the Waterfront, his two King Lears in Boston and New York, starring F. Murray Abraham, and his Two Gentlemen of Verona in Central Park. By extension, I had also attended Richard Kavanaugh’s last play, Uncle Vanya, at Baltimore Center Stage, and one of Richard Kneeland’s last shows, Long Day’s Journey Into Night at the Arena Stage in Washington. Adrian, in turn, had been at a Dallas luncheon in 1989 when I presented my John Connally biography, The Lone Star, to the Dallas Wellesley Club. In that ballroom of 800 well-heeled guests, I took great pleasure in acknowledging him, since it was right after he had been fired from the Dallas Theater Center, and I was sure some of his prissy detractors were in the crowd.

In 1992 I enlisted his help in this epic enterprise. And a year later, we received a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to write the Galileo script. We tootled off to Italy—somebody had to do it—to scout locations in Rome, Florence, Venice, and Pisa. In some sort of reverse spin, I also made a few trips down to Van, partly out of secret curiosity to see why a cosmopolitan guy like this would give up Providence for East Texas. The answer? His mother, “Miss Mattie,” was still alive.

During our breaks from work we gorged on cheese enchiladas and Lone Star beer at the Two Senoritas over in Mineola. Out of that initial work, we got our first draft. In the summer we had to polish it…okay, comb it…and get it ready for production. As the summer proceeded, I began to have that old sinking feeling of deja vu. Because Jonestown Express was based upon the material in my 1981 book Our Father Who Art in Hell: The Life and Death of the Reverend Jim Jones, I remember well Adrian’s response to someone’s question about how our work then was going. “Well, we have a wheelbarrow load full of material,” he said, “but we don’t yet have a play.” Eventually, somewhat to my dismay, Jonestown Express was referred to not as a play but as a Trinity Rep “event.”

Now with the Galileo script we were lurching toward a unique concept, we thought: A disappointed biographer as narrator. He has published a much praised book about a great figure of the last thousand years, but is left with a decided sense of incompletion. The public remains unaware of the subject’s greatness and humanity, confusing the historical figure with a popular Washington restaurant or a teenage song by the same name.

“Who is Galileo?” the biographer/narrator asks a passerby on a Washington street in his teleplay. “Isn’t he the one who invented the telescope?” the man in the street replies. In television verité, one can actually hear the gnashing of teeth! More importantly, despite the certainty that he has gotten all his facts straight, the writer wonders if he himself has fully understood his subject, much less experienced directly the glory and the agony of his subject’s life. “When I finished the book, I was sure I had gotten the facts straight, the historical truth,” the biographer will say in the teleplay. “Now I want to get to the emotional truth, if there is such a thing as emotional truth in history.” And so the biographer recruits a great theatrical director and an award-winning filmmaker, famous among documentarians for his intimate style of shouting. They, in turn, gather together a gaggle of Galileo experts and a repertory of eight actors, including a star of international reputation.

“Why do you need actors?” one actor asks the biographer as they sit at a rehearsal table at the beginning of the play. The biographer shrugs his shoulders. “Yours is the world of the imagination,” he replies cryptically. “Is it a documentary?” another actor asks. “Not exactly,” the biographer stammers. “I don’t know what we’ll call it. Doesn’t matter.” I like that line. Meanwhile, the shy, retiring biographer must somehow become a powerful, hairy-chested executive producer and raise a million bucks, if an equal amount of money can be raised in the United States. The biographer is way out of his league. But to start the process, the shy biographer and the great director must polish their script for submission to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting for partial funding. Will they make their looming deadline?

“I’ve been combing through our work yesterday, and I’ve realized that we’ve made some mistakes. Quite a few things still confuse me,” Adrian said. We are only days away from our own deadline, and we’re still stuck in the first act. Didn’t Adrian realize that we were running out of time? We’ve been poring over the same material for a month. Our long-distance collaboration had a set routine: the prelims, the work, then my typing the changes and faxing them down to his performance barn. The next day: the prelims, then the combing of yesterday’s work. I decided we’d better change our routine. The pile of reworked and discarded sheets in my office was two inches high.

That Adrian had a fax machine at all is an amazing fact. He had realized, apparently, that if in 1997 you’re going to have a performance barn in East Texas, it has to have a fax machine. We are soulmates on the technology thing. I had a typist until 1989, the year that she was 94 years old and had only one eye and one kg. That’s when I decided to get a computer, but my syntax has never been the same. Modern as this long-distance collaboration made us feel, as if it were a theatrical equivalent of a bicoastal marriage, I now decided to send him tomorrow’s rather than yesterday’s work and wondered how long I could get away with it. Not long.

We were not writing a teleplay, I decided. We were weaving an Oriental rug. The vocabulary came from L’Atelier (and put me in the mind of George Martin’s splendid performance in the 1981 Trinity Rep production of Jean-Claude Grumberg’s play of the same name). We “stitched” and “hooked.” We were concerned with the main thread, with the “clothesline” or the “through line,” with the loose knits and strands, with its thickness, the tightness of its knots, its durability. In the end, for there was an end, Adrian knew all along that we would make our deadline. We had to look not only at the entire rug—its design, the texture and depth of its colors—but also whether its threads “tracked” evenly through the entire intricate work. It was as if the final tracking were more in the nature of brushing than combing. (He objected to the word “brush.”) “That line won’t act,” he said. “I can’t make that line work.”

At last, Adrian pronounced himself satisfied. And if he was satisfied, I was satisfied. It was ready to be shipped off to the casbah of the PBS market. That was the creative side, the literary and the dramatic side. But we were also engaged in a political process. The readers were about to take over. They were the true lions now. So one hot day in August I invited our CPB project manager over to my castle for lunch. I had given her the book on the artistry of Adrian Hall, but I wanted her to “experience” Adrian. She needed to know that this giant of the theatre was not English but very American, for among those outside the crusaders of the “regional theatre movement” of the past 30 years, he was often confused with Sir Peter Reginald Frederick Hall of Royal Shakespeare Company fame.

It was a risk. In thinking about Adrian, the words “politic” or “diplomatic” do not often come immediately to mind. Still, I wanted her to hear directly his thoughts on the death of costume drama in the post-Cecil B. DeMille era, to hear the Grotowski echoes about the non-essentials of costume and set and the transcendent importance of the text. I wanted her to feel his high sensitivity about that protean beast known as “the audience,” to listen to his thoughts about how actors could be used deftly to search out the emotional truth of a historical character in a true docudrama. It was a risk, but I thought she could handle it, for she was already a booster. I handed her the phone. Literally for the next 35 minutes, the only words I heard her utter were “Uh huh,” and “That’s right.” Afterward I called him up for his impression.

“The conversation went very well,” he said.

James Reston Jr. is an author and playwright who worked closely with Adrian, most notably on Jonestown Express, which had its world premiere during the 1983-84 season at the Trinity Square Repertory Company in Providence and was published by TCG in 1984.