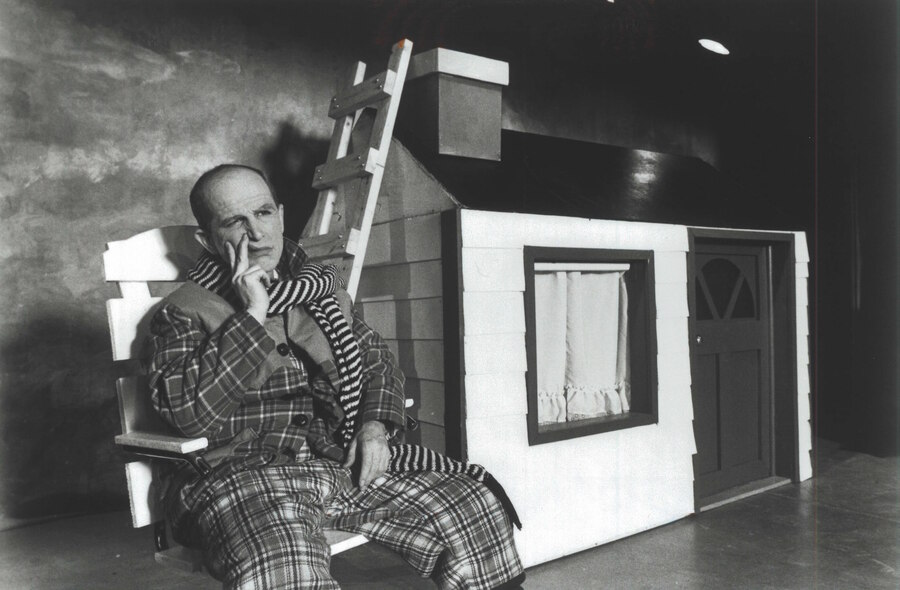

Everett Quinton, longtime performer and leader of New York City’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company, died on Jan. 23. He was 71.

Walking toward a bookstore at 6th Avenue and 8th Street back in 1985, I recognized the man coming out the doors immediately as the founder of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, Charles Ludlam—the devilish grin and glint in his eye made me feel he wanted to take a bite out of me. But my gaze was drawn to the man he was with, his partner, Everett Quinton, whose wide-eyed, blinking, enigmatic face reminded me that he and Ludlam had recently expanded my understanding of what theatre could be when I saw them in The Mystery of Irma Vep.

Two years later I was in the Tiffany diner on Sheridan Square when I introduced myself to Everett. Tiffany was populated by an assortment of West Village denizens and theatre people. On any weekday morning you might possibly see H.M. Koutoukas, Robert Patrick, Irene Fornés, Joe Chaikin, Marshall Mason, or Everett. Sometimes there were barflies and other all-nighters decompressing; a trans woman who worked as a nurse was often there before and after her shifts. And there was a gentle person with whom I smoked cigarettes from time to time named Marsha P. Johnson. Flowers in her hair, blouses, bangles, chatty—it was Everett who eventually explained to me that she was one of the Stonewall girls.

Of course, people came there to eat, but it was a large diner, and many were there mainly to smoke cigarettes and drink coffee; tables were shared; there was an easy conviviality. It was a low-key neighborhood place, and as gay as a kite in the sky. In the East Village where I lived for over 30 years, it was not surprising to daily pass any one of hundreds of Downtown artists, performers, and neighborhood eccentrics on Second Avenue. Though the West Village could feel conformist, there was something about Tiffany and Christopher Street that was just as bohemian and welcoming as the East Village. Everett and I were regulars.

At the time we met, Everett was directing Big Hotel, his first production at the Ridiculous Theatrical Company after Charles Ludlam had succumbed to AIDS six months earlier, in May 1987. When they met in 1975, Everett was a recent Navy veteran with no theatre experience, yet within a year he was not only doing costumes and wigs for the company, he was also performing. Under Ludlam’s tutelage, he grew into a fearless comedian and a serious actor, both in and out of drag. At the time of his death Ludlam was already considered a genius by many and had recently come to the attention of the rest of the world with appearances in film and television, playing Hedda Gabler in Pittsburgh, and being tapped by Joe Papp to direct Titus Andronicus in Central Park that summer.

Everett’s grief was complicated by the expectation that he would continue Ludlam’s legacy by keeping the Ridiculous Theatrical Company open, which he did. It was daunting, but he loved the challenge, and it gave him an anchor. Along with Steven Samuels, Steven Asher, and others, he kept the Ridiculous alive another 10 years, producing revivals and new plays, notably his one-person adaptation of A Tale of Two Cities, Ludlam’s Camille and Der Ring Gott Farblonjet, and Georg Osterman’s Brother Truckers.

In the summer of 1991, I mentioned to Everett how excited I was to have been cast in a revival of Rochelle Owen’s 1968 inter-species carnal romp Futz! at La MaMa, and that director Tom O’Horgan had insisted every actor in the ensemble play an instrument. I chose the mountain dulcimer. On opening night, I was summoned to the empty house before curtain, and there was Everett. He gave me the dulcimer that Charles Ludlam had played every night in Irma Vep; he’d finally begun to unburden himself of the massive amount of books, props, wigs, and stuff belonging to Charles that he couldn’t bear to keep or throw out. Knowing this made his kindness all the more poignant.

After Everett closed the Ridiculous in 1997, he began to work as an actor regionally. When I ran into him one day, he cheerfully cracked that he didn’t only have to work in New York, because “they do plays all over the country!” He later acted in or directed multiple Ludlam revivals Off-Broadway, including The Mystery of Irma Vep, Conquest of the Universe, or When Queens Collide, and The Artificial Jungle.

In 2011, director Jonathan Warman assembled a cast of Downtown performers for a bizarre and funny late Tennessee Williams one-act, Now the Cats With Jeweled Claws, which opened at the Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival, then had a run at La MaMa. The day after I came on board as dramaturg, I received an email from Everett asking me to send him everything I had about that play and the late work of Williams as soon as possible.

Everett and I became the kind of friends who stayed in touch, attended each other’s plays, remembered birthdays, and reconnected every few years. I wouldn’t claim to have to have known Everett better than other people, but I do feel I can make a few observations about him. He was a genuinely humble person, deeply skeptical, articulate, always fabulous, and he didn’t put up with what he considered to be bullshit from anyone. Everett had a rigorous work ethic, and as a director he could be tough in rehearsal, especially with younger actors, but he was also generous and playful. He was a connoisseur of opera and 20th-century classical singers, followed politics with zeal, raved against what he called the “anti-queer brigade,” and always spoke up for the LGBTQ community.

Everett was also a dedicated Catholic, later a Lutheran, who rarely missed church and who also freely mocked the hypocrisy and camp of organized religion. A decade or so ago, Everett adopted a scruffy little terrier he named Raindrop that he doted on and took everywhere. Everett’s smile was electric, with a bright row of large, straight teeth surrounded by deep laugh lines. His inscrutable resting face often looked as though someone had painted Buster Keaton as the Mona Lisa.

Everett Quinton lived and worked with Charles Ludlam for 14 years. He then spent the next 35 years making his reputation as an actor and director. How difficult to find yourself without your partner, collaborator, and mentor, yet with public expectations pressing down on you. Nevertheless, Everett created his own legacy and will remain beloved by the theatre community.

Thomas Keith has edited the Tennessee Williams titles for New Directions since 2002, he is an associate adjunct professor at Pace University, works as a dramaturg, and his writing has been published in American Theatre, Gay & Lesbian Review, and Studies in Scottish Literature.