This article is adapted from Survivors of a Future That Never Happened: A Cultural Review, 1974-1994 (Montreal Publishing), available on Bookshop.org and Amazon.com.

“The Theatre of Images”—a term coined in the early 1970s by Michel Guy, director of the Avignon Festival in France, and popularized by Bonnie Marranca in Performing Arts Journal—was, along with performance art, the major development in the live arts of the ’70s. The surge of theatricality in the postwar avant-garde had opened tremendous reservoirs of collective feeling across the performing arts of Lower Manhattan, climaxing in the visionary theatre collectives of SoHo, the capstone of one of the great eras in 20th-century American theatre history. It was an era of formal precision, ritual enchantment, therapeutic play, and public participation, reflecting powerful communal urges in a world that seemed to many to be on the verge of some cataclysmic upheaval.

“Meredith Monk was born in Lima Peru” ran the playbill bio at the ill-starred Billy Rose Theatre Broadway event in 1968, continuing: “grew up in the West riding horses/is Inca Jewish/lived in a red house…/started dancing lessons at the age of three because she could not skip/did Hippie love dance at Barney’s Roaring 20s in California/has brown hair.” Equal parts countercultural fantasist, wild child, and visionary saint, Monk at age 25 was an American original. Her theatrical vision was rooted in the voice. Her vocalizations were pre-verbal: nonsense syllables, repeated consonants and vowels, whining shrieks, microtonal yelps, monkey chatters—a medley of soul sounds capable of surprising expressivity, purity, and range, with a fully developed contralto vibrato shining behind her weirdest howls and folk-inflected syllables, lodging in the mind as ineffable states of being.

Performing in Downtown New York while still at Sarah Lawrence College, Monk plunged into the Happening and Off-Off-Broadway scenes, creating a series of site-specific music-theatre works for unusual environments, augmenting her utopian company, known as “The House,” with additional performers for each event.

The first installment of Juice: A Musical Cantata in Three Installments (1969) was performed in the interior of the Guggenheim Museum on Fifth Avenue. Seventy-five white-clad “angels” chanted and hummed as they spiraled up the museum ramp, exploring the resonant acoustics of Frank Lloyd Wright’s six-stories-high domed space. Later that year, Tour: Dedicated to Dinosaurs was performed in the Dinosaur and Whale Rooms of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., and Tour 2: Barbershop in a museum in Chicago.

Vessel (1971), Monk’s “opera-epic” about Joan of Arc, opened with an overture in Monk’s new loft below West Broadway, traveled to the Performing Garage on Wooster Street in SoHo, then to an empty parking lot transformed into an ancient battlefield and campsite across the street from an old Dominican church, standing in as the site of Joan’s ultimate immolation and martyrdom, represented by thick sparks. (The church was ultimately demolished to make way for the SoHo Grand Hotel.)

A multi-form epic involving more than 100 volunteer performers, Vessel was the richest, most thematically unified work that Monk and the House had yet produced, as well as a magical summation of the larger arts community that SoHo had become.

Robert “Bob” Wilson, born and raised in Waco, Texas, was the son of a middle-class lawyer who was also Waco’s city manager and a housewife whom he claims never touched him until the day he left for college. Wilson grew up “knowing the drama of those who fight to conquer a language,” as an Italian critic would note: Indeed, Wilson may have had learning disabilities, and sometimes still reads with awkward slowness. His early vision would never depart far from the perspective of childhood, as well as its dispensations from the rigors of adulthood.

A gifted therapist, architect, painter, sculpture, and environmental artist, Wilson started out working with authorities who wanted their wards to become acceptable within the normal horizons of institutional life. But Wilson “encouraged them to do what they wanted to do,” he said years later, “instead of trying to correct or teach.” Autistic kids—those feral children of the psyche—seemed to him to possess a special innocence, an almost mystical insight into human experience.

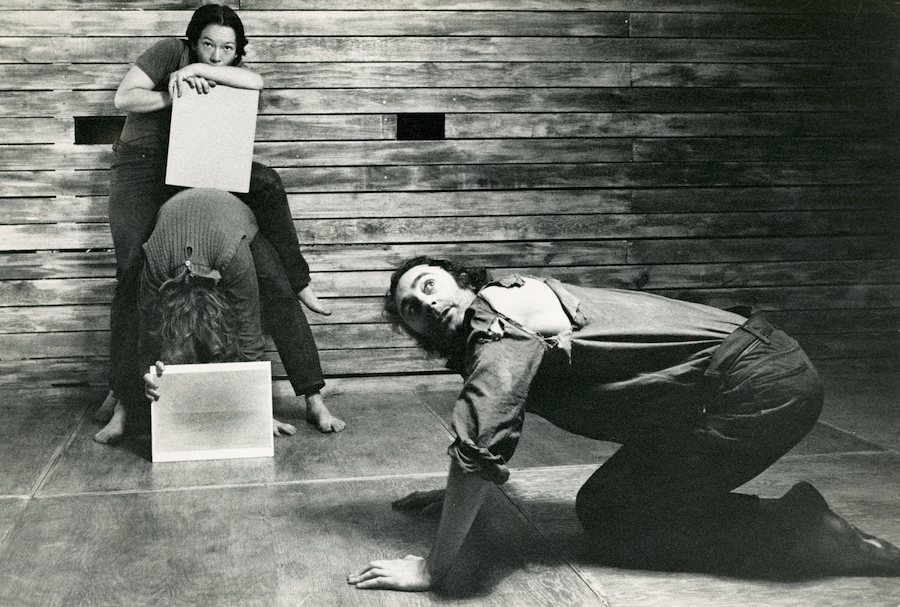

Wilson took over the Open Theater’s former Spring Street loft in 1967 and introduced “madness workshops,” depoliticized from the heights of the Living Theatre’s Paradise Now (1968) and recast as therapy. Through a series of workshops and performances, Wilson became the leader of a group of amateur disciples called the Byrds, named after the Byrd Loft—the sort of folks Brecht once called “ordinary people, borderline psychotics”—whose free-spirited behavior proved crucial to the development of Wilson’s theatre. Wilson’s madness workshops became a forum for improvisational frenzies, ritualistic slow motion, and the mechanical repetition of meaningless tasks, often performed under the influence of psychoactive drugs, though sometimes not. Like many SoHo performing artists, Wilson worked with “found” personalities: volunteers, friends, and acquaintances who had little in common except that Wilson saw something in them.

“We lived on rice and moonbeams. Nobody had jobs,” one remembers. “Not when you got up at five in the morning and didn’t go to bed until three in the morning. We were at the Spring Street loft working 18 hours a day. Oh, it was crazy.”

Wilson’s main departure from nearly all of his Downtown contemporaries was his embrace of the proscenium arch. His works took place in framed environments where objects could float in space and animals appear in drawing rooms, on a time-scale fundamentally different from the rhythms of life—”time to think,” as Wilson put it. His psychologically inscrutable theatre proceeded with the leisureliness of dreams, dark fantasies of psychosexual disaster paraded with an architect’s sense of scale and a child’s whimsy. For The King of Spain (1969), Wilson built 20-foot-high cat’s legs that strode across a Victorian drawing room, which split in two, revealing a sunny “exterior,” inspired by sculptor Gordon Matta-Clark’s practice of sliced-up architecture.

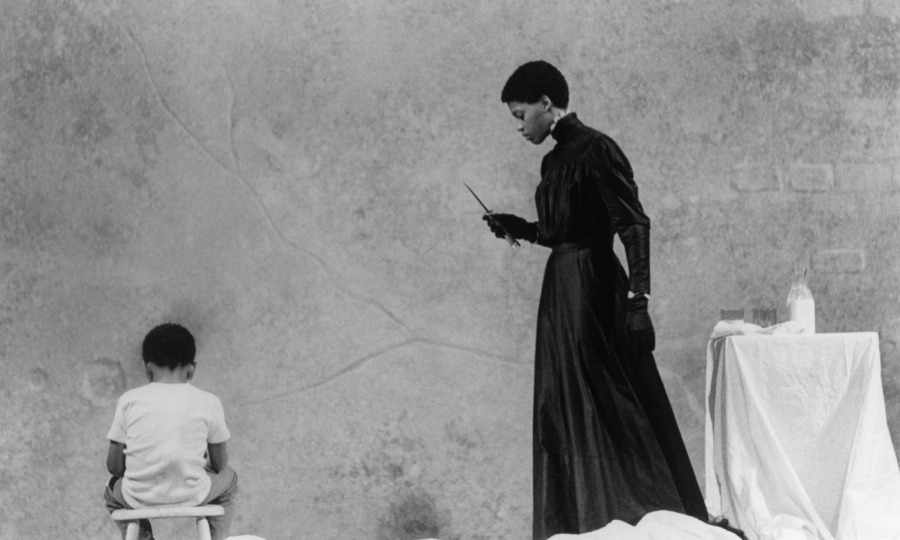

Wilson’s themes of impairment and compassion for the helpless found their muse in 1968, when he rescued a 10-year-old Black orphan named Raymond, who was deaf and mute, from a beating at the hands of police. In a new series of workshops, the Byrds imitated Raymond’s sounds and movements, which Wilson shaped as dance, mime, and dream imagery into a three-and-a-half-hour mystery play that seemed to exist independently of analysis. Deafman Glance premiered in Paris in 1971 as a vision of extraordinary integrity and beauty. Le Monde hailed it as “a revolution in the plastic arts that occurs once or twice in a generation.” The aging surrealist Louis Aragon, who had damned the rebels of ’68, praised Wilson’s “extraordinary freedom machine” in the form of a letter to his long-estranged friend, the father of the Surrealist movement, André Breton, who had died five years earlier. “The miracle came about long after I stopped believing in them…The world of a deaf child opened up to us like a wordless mouth…I never saw anything more beautiful in the world since I was born.”

“All of Paris read that review,” Wilson would tell me years later, “and in the morning I was famous.”

This climactic moment of postwar theatricality in the ’60s was accompanied by, and indeed required the destruction of, all confining visions of drama. By 1968, Richard Foreman believed that “the theatre became hopeless,” but what theatre could still do was prod audiences into an awareness of the disaster of the world.

Born in 1937, the only child of an upper-middle-class Scarsdale couple whom he thought were his natural parents, only to learn as an adult that he had been adopted, Foreman grew up an excruciatingly shy, bookish youth who didn’t like crowds. His discovery of theatre at age 9 provided him with means for contacting other people and ways to interact “with an authority not otherwise mine in my kid life.”

He studied creative writing at Brown, then took a Master’s in Drama at Yale, and hated both experiences. He arrived in Lower Manhattan in time to see the Living Theatre productions of The Connection and The Brig, which impressed him enormously. Jack Smith’s seminal Rehearsal for the Destruction of Atlantis in 1965 demonstrated to Foreman’s satisfaction that being “mentally ‘non-handleable'” was the proper activity of art. The notion of exploiting one’s own awkwardness led him to Gertrude Stein, who also evoked a “continuous present” in a non-empathic, irrational world where the best response was mental clarity. “That’s what I’m interested in,” Foreman said.

Foreman’s productions were a bizarre world of disassociated epiphanies, buzzers, bells, and fractured speech, revealing the off-balance rhythms of a mind ceaselessly at work—excluding nothing, not his ripest erotic fantasies or his most maladroit pensées. Performers appeared in two-dimensional tableaux, moving in mechanical repetition or popping up from behind distorted doors and mirrors; naked women, as faceless and impersonal as figures in a de Chirico painting, blankly addressed audiences.

Like Monk and Wilson, Foreman worked with “found” friends and acquaintances, including many who had no thirst or even talent for performing. He would suppress even the slightest expressiveness or collaborative input, personally conducting proceedings from a sound-and-light board in full view of the audience—a powerful image of authorial preordination and control. Foreman’s hysterical acceleration of Brecht’s “alienation effects” attempted to combat emotional manipulation by replacing it with surprising jolts, some involving physical discomfort, bright lights, rock-hard seats, ear-splitting buzzers, thuds, gaps, and sudden movement, while otherwise offering only the barest hints of narrative, theme, or psychology.

“Art must keep man rooted in imbalance,” Foreman announced in his first “Ontological-Hysteric” Manifesto—a term he coined to evoke “the danger that arises when one chooses to climb a mountain and halfway up one wishes one hadn’t.” The most uncompromising theatre artist of his generation, and along with Monk the most original, Foreman wanted “to give courage to ourself and others to be alive from moment to moment which means to accept both flux…and the perceptual constituting and reconstituting of the self.”

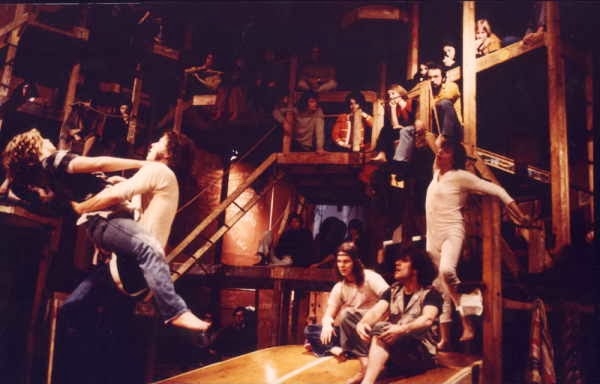

The theatre that went the furthest of all the post-revolutionary SoHo collectives in defining the liberation of performers and audiences as material for the stage was The Performance Group (TPG). Its principal intellectual force, founder Richard Schechner, was a 30-something NYU theatre professor whose stewardship of The Drama Review in New Orleans represented his early attempt “to restore virginity to the theatre, and purpose to theatre workers,” in part by introducing the achievements of European high modernism to American artists. When The Drama Review relocated from Tulane to NYU on Washington Square in Greenwich Village, Schechner created his own company, hoping to use the Polish director Jerzy Grotowski‘s core message—”that emotions and physicality are the same thing,” as Schechner later stated—to set himself up as leader of 10 NYU acting students in a former garage on Wooster Street in SoHo to work on an adaptation of The Bacchae.

Audiences arrived for the first performances in June of ’68 with the Bacchantes already moving along a maze-like system of towers, catwalks, and platforms ringing the performance space. An actor, clothed during the first few months of performance but naked after December, strode into the arena to announce that he, William Finley, was actually the god Dionysus, and that he had come “to establish my rites and rituals…and to be born, if you’ll excuse me.” What followed was “the birth of a god,” which Schechner, a cultural anthropologist as well as a drama theorist, had lifted from an Inuit birth ritual. Naked women stood with their legs spread, pressing groins against buttocks, writhing and groaning while Dionysus squirmed between their legs across the bare backs of a row of prone men.

Once “born,” Dionysus invited viewers to celebrate his nativity by “having a groovy time tonight”—which was all the prompting some audience members needed to remove their clothes and join in an ecstatic dance to flutes, drums, and cymbals. Equal parts group therapy, sacred ceremony, and countercultural freak show, Dionysus in 69 (even the title was a come-on) was a hippie-dippy Euripidean orgy that instantly put The Performance Group on the national theatre map, scandalizing local authorities as well as classical Greek scholars on its subsequent national tour, producing what actor Patrick McDermott termed “a pan-sexual, flesh-vibrating, universal eroticism.”

Behind closed doors, these celebrants of a New Age Mass were a collective in turmoil. Shortly before Dionysus went nude, a year into the group’s existence, an actor stopped a rehearsal to demand that they “stop sweeping shit under the rug and start dealing with one another,” as Schechner later wrote. With the help of a therapist, the situation improved, but by the time the show closed in July 1969, much of the audience participation had either been modified or dropped. As one actress put it in a note to the director, “I didn’t join the group to fuck some old man under the tower.”

A new environmental work went into rehearsal, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Makbeth, which Schechner described as “an angry play of blood, power struggles, betrayals, fleeting contacts, brief flashes of quiet punctuated by screams,” consciously reflecting dynamics within the group. Makbeth’s unpopularity with actors, audiences, and critics only deepened the crisis of authority, which led Schechner to re-assert his power, interiorizing the role of old King Duncan, fated for assassination. When Makbeth closed in January 1970, the original group disbanded in recrimination and dislike. Schechner was probably correct in saying that the problems had come as much from the streets as from within the company itself.

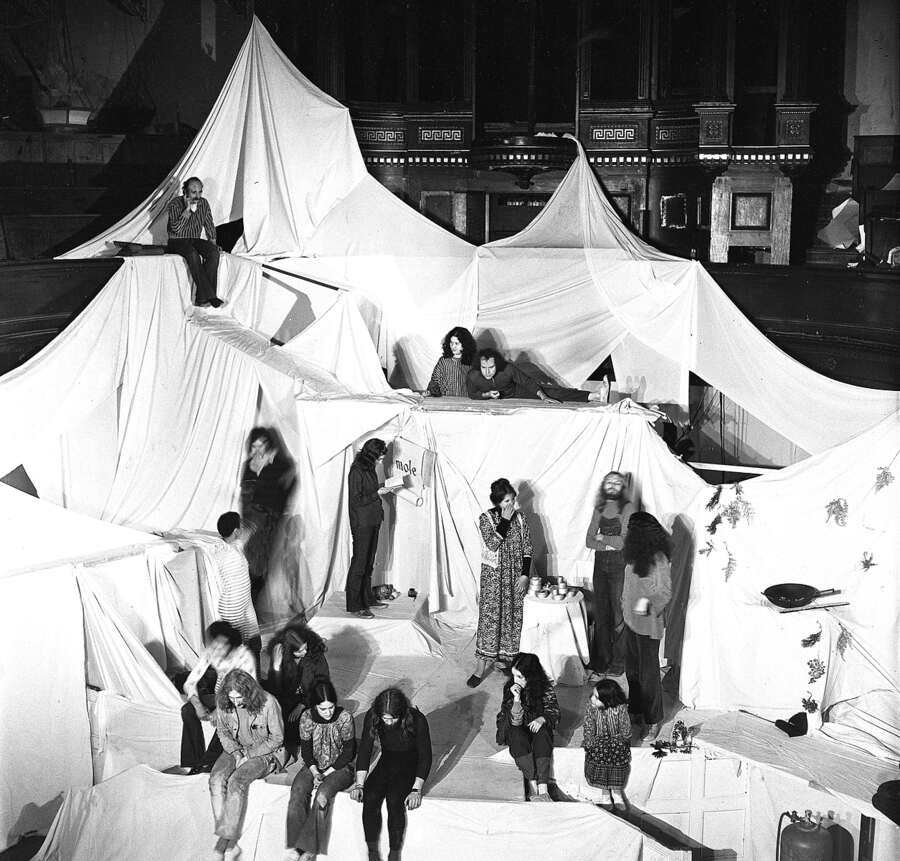

The Performance Group (TPG) reconstituted itself in March 1970 what it would think of as Year One of an entirely new company, with key figures including actors Joan MacIntosh (who became Schechner’s wife), Stephen Borst, and Spalding Gray, who had arrived late in Makbeth rehearsals. At a residency at Swarthmore College in upstate New York, Gray met Elizabeth LeCompte, a New Jersey-born visual artist who became Schechner’s assistant director. With this new, tightly knit company—”a collective, artistic, participatory democracy,” as Gray later recalled—work began on a dark rebirth: Commune (1971) was “a play about Middle America, by the children of Middle America—no copouts, no kidding,” as Schechner wrote in The New York Times. Congealing around fantasies of violence—most vividly, the My Lai massacre and the Tate-LoBianco murders by the Manson family—Commune evolved in part over a seamless round of summer workshops, parties, mountain picnics, skinny dips in lakes, and acid trips in the woods outside upstate New Paltz.

“The changes, man,” said one character. “The changes are what it’s all about.”

Touring in Poland, Commune set off a riot when hippies bent back the bars of a backstage bathroom window and invaded the theatre. Back on Wooster Street, company members were cooking, showering, and sleeping in the theatre, as director Tom O’Horgan had wanted to do with the company of Hair during the musical’s Broadway run.

TPG’s all-night dance parties were drugged-up, drunken bacchanales. Schechner was accused of exploiting participants during one all-night trance dance. “The charges struck home,” he later wrote. “Was the ecstasy dance just an ornate structure sheltering simple erotic impulses? But at the same time, I wondered, what was wrong with that?” LeCompte was not alone in thinking that Schechner’s sense of his position in the company had taken precedence over the work itself.

In October 1971, Schechner and MacIntosh left for a seven-month-long pilgrimage to Asia and the Pacific. On their return in April 1972, Schechner discovered that LeCompte had revised Commune, empowering actors to express their unhappiness with the original production and create a new one. Collective imperatives pointed towards a need for democratic reforms: TPG reconstituted itself again as a not-for-profit entity, with all members legally part of its decision-making processes. Schechner’s dream of presenting performers as themselves, within the contexts of their own lives, had liberated their voices, but at the same time had caused him to lose control of them—marking a shift in experimentation that launched The Performance Group into its greatest period of work, post-1974, and would eventually lead to the creation of an entirely new entity without Schechner, known to this day as the Wooster Group.

Unique among the collectives of the SoHo era, Mabou Mines never surrendered to utopian fantasies, never identified with therapeutic goals, and never entirely abandoned the traditional resources of the trained actor. Responding to the era’s crises of authority, Mabou Mines dispensed with the role of artistic director altogether, sanctioning all participants—directors, actors, composers, technicians, and visual artists—to function as equal partners in the creation of theatre worlds. Emerging in part through the Downtown’s visual and musical arts communities, Mabou Mines touched upon every major ism of the ’70s, from minimalism and post-minimalism to Buddhism and feminism. This collective of radical individuals fused the visually oriented theatre of Wilson and Foreman with the actor-centered theatre of Joseph Chaikin and Jerzy Grotowski, merging images and words when not many experimental companies were employing language as a form of enchantment or song.

Mabou Mines’ origins reach back to the time Ruth Maleczech and Lee Breuer met as undergraduates at UCLA in 1957. After graduation they gravitated to the performance scene in San Francisco, where they met a recent drop-out from a Stanford doctoral program in philosophy, JoAnne Akalaitis, who had moved to the city to “explore the emotional side of existence” in the theatre. This early coming together of core membership broke apart in the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination and the thickening drug scene in North Beach. Breuer and Maleczech headed to New York, and in January 1965 caught a tramp freighter to Greece. Akalaitis took an apartment in Greenwich Village, hoping to pursue a more or less conventional acting career. She also renewed contact with a man she had met in San Francisco several years before, the Juilliard-trained composer Philip Glass.

It was in Paris, not San Francisco or Manhattan, where the founding members of Mabou Mines first convened. Glass had a Fulbright Scholarship to study music with Nadia Boulanger, and Akalaitis joined him in October, in an unheated Left Bank carriage house on the Rue Sauvageot that had formerly belonged to the painter Hans Hofmann. Vacationing in Greece in a battered car, they reconnected with Breuer and Maleczech, who had been living in a horse stable on Rhodes. The foursome moved in together on the Rue Sauvageot and struggled to break into the English-language theatre scene in Paris.

Along with David Warrilow, an elegant Englishman of Irish extraction, they began to rehearse a recent one-act play by postwar theatre’s greatest minimalist, Samuel Beckett. Play (1964) featured Glass’s first minimalist composition: ten 20-second-long solo phrases for saxophone, two lines of two notes in alternating, pulsing intervals. Play’s success d’estime tempted them to start a theatre company in Paris, but Akalaitis wanted to return to New York—though not before she and Glass took a long overland trip to India. In Darjeeling, the gateway to the Himalayas, Glass accepted a Tibetan Buddhist, Domo Geshe Rinpoche, as his teacher; Glass would later assist in Rinpoche’s resettlement in upstate New York.

Returning to New York City after two-and-a-half years away, Glass and Akalaitis moved into a two-floor apartment above a 23rd Street deli and immersed themselves in the “politics, factions, stratagems, and worlds within worlds that make up the New York art scene,” as art critic Robert Pincus-Witten observed. JoAnne wrote Ruth and Lee in Paris, observing that Manhattan was “violent and frightening,” but noted exciting developments in the visual arts and dance. Maleczech suggested they attend a three-week workshop in the south of France with the theatre guru of the moment, Jerzy Grotowski, who would provide another crucial element to what became Mabou Mines.

Grotowski viewed acting less as an acquisition of skills than an eradication of blocks. Both Ruth and JoAnne considered Grotowski’s approach brutal and sexist, but the dazzling presence of Grotowski’s lead actor, Ryszard Ciezlak, somehow vindicated Grotowski’s methodology, demonstrating that an actor “could be a creative, rather than just an interpretive artist,” as Maleczech later explained.

Just before Christmas 1969, Lee, Ruth, and their infant daughter, Clove 333 Galilee, joined Phil, JoAnne, and their daughter Juliet above the 23rd Street deli, with Warrilow following a week later. Glass kept the household going by doing plumbing work for the SoHo loft boom, while Breuer struggled with writing a “performance poem” about the coming-to-consciousness of a horse. Early works-in-progress of The Red Horse Animation attracted the attention of Ellen Stewart of La MaMa, who had a three-year grant from the Ford Foundation, enabling her to offer the company production dates and $50 dollars a week per member. With the promise of early winter performances at La MaMa, the group traveled a thousand miles northeast to a campground on the Eastern shore of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, a 50-acre property Glass and a close friend had recently purchased after Glass had inherited $10,000 from the sale of one-sixth of a Baltimore parking lot. When the new theatre needed a name, JoAnne thought of a run-down former coal-mining village a half-hour south of the property.

Mabou Mines premiered Red Horse at the Guggenheim in November 1970. The Times’ Clive Barnes suggested they all go back to the mines. Even the Voice found the company “lost in formalities, in gentility, in its celebrations.” The critical wipe-out ended when Breuer returned to Beckett, premiering Play on a double bill with Red Horse at La MaMa in April 1971. Mabou Mines’ highly original realizations of Beckett’s one-acts would eventually be recognized across the U.S. and Western Europe. Mabou Mines would receive an Obie Award for General Excellence in 1974, but company meetings had become increasingly rancorous, degenerating into business wrangles, inspiring Breuer and Warrilow to dream up the cheapest Beckett they could think of: The Lost Ones was a monologue adapted from a short story about a race of people trapped in a purgatorial cylinder. Audience members were given small binoculars to observe Warrilow manipulating tiny toy figures along a circular wall and platform two feet in diameter, described in the text as “50 meters round and 18 high.”

A brilliant production concept and an extraordinary performance intertwined. Mabou Mines Performs Samuel Beckett opened in the spring of 1975 at the Theater for the New City on Jane Street in the West Village, comprising Play, Come and Go, and The Lost Ones. The Times, Newsweek, and Vogue all raved. The Beckett trilogy marked the company’s decisive shift into larger theatre worlds.

SoHo, the home base of the “Theatre of Images,” by mid-decade had become home to more than 64 visual art galleries. Leaving its collective idyll, SoHo also slipped its ghettodom: What the Times’ critic Hilton Kramer described disapprovingly (in 1973) as “the Age of the Avant-Garde” had made contemporary art a focus of interest among a growing public, not just in New York, but across America, Europe, and Asia as well. An interdisciplinary arts community without parallel since Paris in the ’20s was exiting its “closets of self” to usher in, among other things, what could fairly be called what Schechner called it, “an Elizabeth era” (after Liz LeCompte, who would soon co-found the Wooster Group) in 20th-century American theatre—an age that would influence theatre artists and audiences literally around the globe in the coming decades.

Robert Coe (he/him) is an author, journalist, playwright, and screenwriter living in Jersey City, New Jersey.