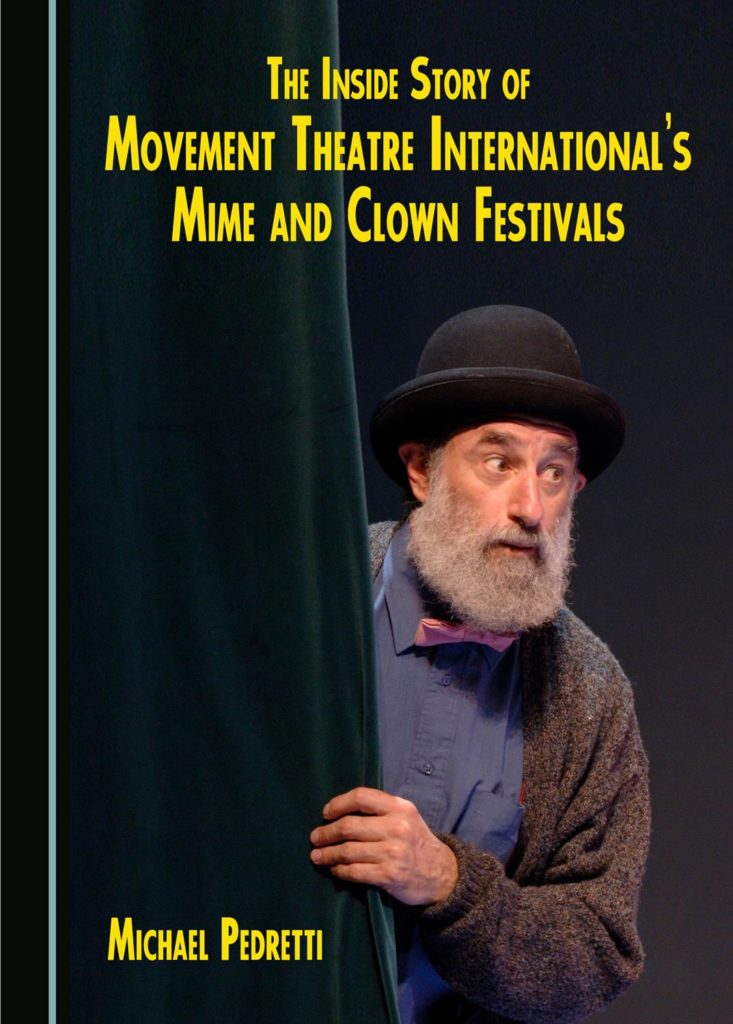

The following is an excerpt from Michael Pedretti’s new book The Inside Story of Movement Theatre International’s Mime and Clown Festivals. (AT readers can use the code PROMO25 for a 25 percent discount, courtesy of the author.)

On opening night of the 1988 International Movement Theatre Festival in Philadelphia, Robert Shields and Litsedei performed several pieces from their full-length shows. Shields was, without dispute, the most well-known mime in America, and Slava Polunin, Litsedei’s leader, was, as Dan Geringer wrote in the Philadelphia Daily News, “as popular in the Soviet Union as Robin Williams is here.” Shields, performing the world premiere of his show, informed me this was a scary evening for him, as he had never performed solo for that long onstage. No one, including me, could have suspected that while watching him reinterpret Robbie the Robot and delight us with a piece titled “Radio Station of Your Mind,” in which the radio went inside his head and changed stations at will until it tuned into “the radio station of your mind.” William Collins, the main theatre critic in town, noted in The Philadelphia Inquirer, “That is scary enough. But the white-faced character ends up confessing ‘I don’t know who I am anymore’ and imagines himself to be ‘the white line on the freeway.’”

Shields’s work, as always, was crisp and disciplined, but darker than what the audience had seen on television when he performed with Lorene Yarnell. He looked almost embarrassed when the audience jumped to their feet and cheered wildly, demanding repeat curtain calls. I heard artists and audience members say at intermission, “I’d hate to have to follow that act; it will be hard for anyone to top such a brilliant performance.” Polunin and his crew, in their American debut, were more than up to the task. William Collins described the work:

Litsedei, which translates ‘The Jesters,’ are engagingly funny, individually and collectively. In outlandish clothing and distinctive makeup, they grapple with inanimate objects and each other in inventive ways. They get tangled up in chairs and in each other’s costumes.

At times, they go right to the essence of a human dilemma. Example: One of the loonies finds himself immobilized by the other two, who happen to be standing on the scarf he trails behind him. His two buddies smile sympathetically without realizing that they are his problem.

It was a stunning evening of theatre, the air full of excitement because of the premieres, because America was onstage with the USSR, because it was the opening of the festival, and because all the participants knew MTI was on the road to a new adventure with the soon-to-be MTI Tabernacle Theater, where the reception for the festival gala was held after the performance. Among the guests at the gala and the performance was His Excellency Klaus Jacobi, the ambassador of Switzerland. He was joined by most of the artists from the festival, many local dignitaries and representatives from the embassies of Norway, Poland, Italy, and USSR.

Following the performance, which initiated the new International House Theater, the entire audience strode across the street and entered the former sanctuary of the United Presbyterian Tabernacle Church. The crowd was introduced to the beautifully appointed space, which we highlighted with theatrical lighting and the architectural sketch of the proposed theatre. The fact that they saw the stage floor already constructed helped everyone to envision what the theatre might become. In his review of the evening, Collins captured in one sentence what I hoped was about to happen: “For the next 17 days, dignity will be routed wherever it appears, all conventional rules of behavior will be suspended, the normal operation of the laws of probability will be in abeyance.”

The next evening, Litsedei officially opened the festival with Assissyay Review. They created a world of curiosity, play, and discovery. It was poetic magic; it was the definitive Theatre of Joy. When a couple dozen beach balls and two huge, cloth-covered balloons that seemed to want to float dropped from the ceiling in the last sketch, the audience was enchanted into playful ball tossing. The sternest and most dignified audience members gleefully whacked the balls into the air in a wishful chance to suspend both ball and time.

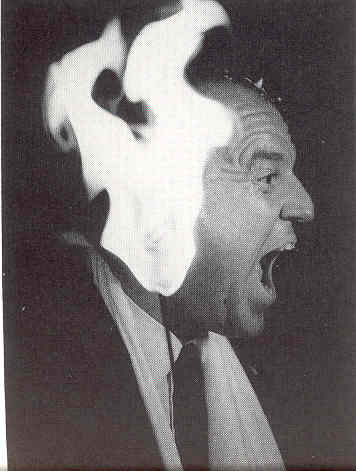

While everyone loved the gentle antics of Litsedei’s clowning, participants and the public either loved or hated the work of Leo Bassi, who was also on the festival program. Playing the New Neronian, Bassi confronted the audience. The show began with his entrance, arm in sling, coming up to a blown-up Pennsylvania license plate with the motto, “You’ve got a friend in Pennsylvania.” His look of “Sure I do” scorn captured the audience—especially those who had read on the front page of the Inquirer about his being attacked on South Street.

Bassi’s New Neronian is an aggressive thesis on violence and control. At one point, Bassi locked all the theatre doors and threatened to burn down the theatre. A very nervous audience played along with him—some to a larger degree than others. Then Bassi poured what smelled and looked like gasoline over the stage floor and around the set and lit a flaming torch. He moved anxiously and intensely over the stage, encouraging the audience to believe they were in imminent danger. He came out to the audience, threatened to burn one of the audience members, selected one and then backed off with an apology.

He apologized, not for intimidating the audience member, but for not burning his shirt, for this meant that the poor audience member would not, much later in his life, be able to pick up the burned shirt and show it to his grandson, telling him about the time he had gone to a live performance and this crazy man, Leo Bassi from Italy, burned a hole in his shirt. It would be a lost moment for the audience member with his grandson, he said. Maybe the audience member would even have been part of a club of people from all over the world who had their shirts burned by Bassi, and in his golden years he would be elected president of the club. Bassi’s failure to burn his shirt took away this opportunity of prestige in old age, he said.

And so the evening went, in fiery, forward-lurching rhythm, with Bassi challenging the audience’s perception of truth, tolerance, and totalitarianism. Most in the audience were mesmerized by the neo-fascist Nero lookalike character who demanded faith and fear, and realized Bassi was angry and fearful of the worldwide trend toward strong neoconservative governments. Others hated the show, with some thinking that Bassi was worshiping the Nero character. He did indeed walk the finest line between scorn and adoration.

Nonetheless, everyone loved watching Leo, shoulder in a cast, lie on his back, struggle to lift a piano on to his feet and then juggle it, reproducing the feat that placed him in the Guinness World Book of Records.

Complementing one of the primary themes of the conference, the female in performance, I booked two evenings of shared bills called Women on the Move. The comic-clown evening featured Gardi Hutter, Julie Goell, and Tanya Sadofyeva-Belov. Nancy Goldner, the Inquirer‘s dance critic, wrote that Hutter’s character Jeanne D’Arppo, was “simply wonderful.” Goldner went on to describe Hutter’s show:

With a rat’s nest for hair and dressed in dirty longjohns and a raggedy dress, Hutter walks into a grungy laundry room and promptly plops herself down on a heap of rags to read a book titled Joan of Arc and Other Heroines.

It soon becomes apparent, however, that this laundress doesn’t need books to enter adventure land. She does quite well on her own. Every object around her—a clothesline, a washbasin, a washing machine, a bowl of spaghetti—becomes a vehicle for heroic deeds.

Hutter’s character loves getting out of fixes, but she loves getting into them even more. So having finally figured out how to get out of the washing machine, she joyfully dives back in again. She not only believes in her own catastrophic fantasies, she loves them. So when a paper doll falls to the floor she screams bloody murder, as if it were a real baby. Yet so much does she enjoy the screaming, she sends another doll to its death.”

Version two of Women on the Move featured Elsa Kvamme, who had trained with Eugenio Barba’s company, Marguerite Mathews, who in turn had trained with Etienne Decroux, and Rajika Puri, who was trained in traditional Bharatanatyam and Odissi dance. We saw disciplined performers whose years of training provided a basis for their virtuoso performances. Seeing work from three distinct traditions performed at a high level reaffirmed that there is a direct line between the best of the avant-garde, Decroux, and classical performance.

With 20 performance groups from nine countries—including Geoff Hoyle, the Adaptors, and a traditional dance company performing dances from several villages of Côte d’Ivoire—garnering tens of thousands of attendees for our outdoor events, and thousands for the 47 featured performances, I hoped the whole city would join Leo Bassi in the sentiment that we are citizens of the world, not attached to any land in particular. At minimum, I think we succeeded in calling “into question all your (the public’s) notions about the purpose of theatre and the questions of criticism,” as Kathryn Helene wrote in The Welcomat, and heralded the “rule of unreason” predicted by William Collins.

Concurrently with the festival, MTI produced its fifth National Mime Conference. In addition to seeing performances by each of the featured artists, the over 300 participants at the conference were actively engaged in the panel discussions, attended the five showcases featuring the 15 winners of regional festivals, and most attended one or more of the Commerce Square variety shows.

An open-tent buffet embellished with volunteer street jugglers, clowns, and buskers, held outside the White Dog Café, established an encompassing welcome for the participants who had come from around the country to see their peers and to be confronted with challenging, convention-defying discussion and boundary-busting activity.

The Conference began with a selection of eight workshops ranging from sociopolitical buffoonery to circus skills to an exploration of what is fun. In mid-morning I welcomed everyone to the first all-conference event, a panel discussion exploring the inimitable relationship between movement artists and their audiences. In my introduction I noted again that mimes and clowns, many having graduated from the street to the stage, did not so much break down the fourth wall separating actor from audience as act as if it never existed. I repeated Andre Gregory’s insight about Avner the Eccentric’s show, and Polivka’s announcement that what was most interesting about the movement theatre show was the human-to-human relationship that was established.

To a large extent, during the era of Reagan and Thatcher, the topic of movement theatre shows was not the subject matter—the topic was the human-to-human relationship. I think Gregory was right; the one time I felt like I was a human (instead of a consumer, an entity to be provoked by TV ads, a serf to Reaganocracy, a client to anyone and everyone) was in the theatre, enthralled by a skilled, empathetic, originating artist dedicated to delighting my senses and feeding my soul while asking no more of me than to be completely in the moment with him or her. It may have been the only refuge from the overwhelming effort of everything and everyone in America in the late 1980s to manipulate my every thought and action.

I introduced Gerry Givnish, the arts manager who knew better than any in Philadelphia that performance was an act of love, as the chair of the panel. Gerry, who was also one of the planners for the conference, noted that the discussion might be inadequate for the participants since the panelists were composed solely of performers. He then zeroed in on the issue at hand: “The transaction that goes on in theatre has to do with what the audience expects of the artist and what the artist expects of the audience.”

Each of the panelists made opening remarks discussing their perception of what happens or ought to happen between the performer and audience. Ronlin Foreman set the tone for the panel with a personal revelation that he tried making his own theatre to uncover what he had to offer to an audience. Kari Margolis focused on communication, Leo Bassi on the need for innovative artists to be strong, and Dana Reitz on her efforts to join with the audience for an exploration into the unknown.

I took a moment away from the discussion to glance over the audience to see who was there. In addition to the several dozen entry-level mimes who were regulars at the conferences, I saw the co-founder and co-director of the Living Theater, Judith Malina; the artistic director of the Next Wave Festival, Joe Melillo; five other directors of mainstream international festivals, Nigel Redden (Spoleto-USA), Giuseppe Condello (Mime-Canada), Kaki Marshall (Children’s Theater-USA), Sigfrido Aguilar (Mime-Mexico), and Maranne Welsh (Children’s Theater- Canada); the delightful, compassionate, and brilliant director of arts at SUNY, Patricia Kerr Ross; the inspiration behind African American dance in the region, Arthur Hall; the director of the NEA Theater Program, Rob Marks; New York dancer Blondell Cummings; the actor who played the title role in Jewel of the Nile, Avner Eisenberg; just returned from shooting Children of a Lessor God, Bob Hiltermann, and his partner in Musign, Rita Corey; the head of Gallaudet College, Tim McCarthy; the artistic director of Dance Theater Workshop, David White; the Inquirer critic, William B. Collins; every featured performer from the festival; and three dozen or more performers from the showcase series. I visualized others who would come later in the week, including The Village Voice head theatre critic, Erica Munk (who claimed she hated mime), and the head of the Guggenheim Foundation, Mary Judge.

No question, this was an auspicious collection of performing arts leaders. If all went well, which I had no reason to doubt, we would meet our objective of introducing mime to influential opinion makers of the theatre and dance community and converting them into lifetime enthusiasts. Also in the audience were more than 40 artists from Philadelphia who were guests of the conference and festival for the day.

I surveyed this group of people on the second floor of the Tabernacle building with self-satisfaction in gathering this group of national and local opinion makers. I felt the electricity of having so many creative geniuses all packed into a room lit through stunning stained-glass windows of the Tabernacle Chapel, where we held our first panel discussion. If I wax a little too wondrously here I apologize, but it was a celestial moment in the life of this impresario.

In addition to proving to be an engaging artistic achievement, the 1988 program drew respectable crowds and operated in the black. The institute was well attended, with over 120 participants, and the conference attracted the largest number of participants in our history. The organization also moved forward in giant steps, with important increases in staff positions and managerial leadership.

I think it is fair to say this was the quintessential festival for us. It was the festival I had been trying to put together since 1982. We managed to cover the entire range of movement theatre from dance to talking theatre, without crossing the line into presenting theatre or dance. We presented classical forms, pantomime, buffoonery, comics, fools, eccentrics, clowning, corporeal mime, and, for the first time, an adequate number of female performers. With four groups from behind the Iron Curtain and four from Western Europe, one each from Africa and Asia joining an equal number of American groups, I felt we had never more clearly made the statement that we were citizens of the world.

Michael Pedretti is the author of six books including the dog and i, Begetters of Children, and The Book of Agnes. He founded Movement Theatre International to provide professional training, performance opportunities, and national conferences to encourage the artists and to create a sense of community for the field.