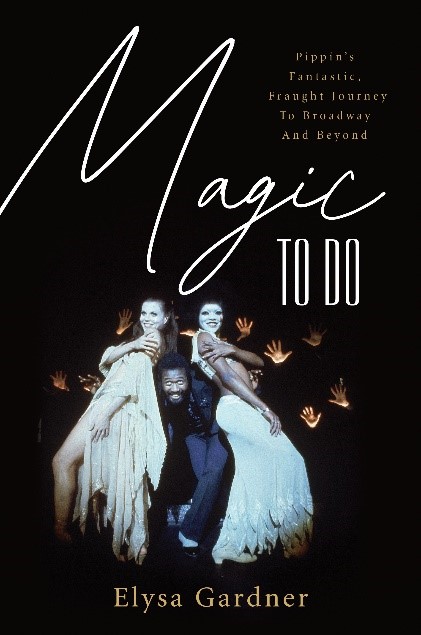

The following is an excerpt from Chapter Eight of Magic to Do: Pippin’s Fantastic, Fraught Journey to Broadway and Beyond, by Elysa Gardner, from Applause Books. Previous chapters explore the show’s origins as a medieval allegory about a prince on a search for meaning and purpose, and detail the often tense creative process among composer Stephen Schwartz, book writer Roger O. Hirson, and director Bob Fosse. This chapter covers the show’s pre-Broadway run in Washington, D.C.

Summer was winding down by the time the Pippin cast and crew rolled into the nation’s capital, and there was still work to be done before the show’s Sept. 20 pre-Broadway opening at the Kennedy Center Opera House. Most of the company members were put up at a Holiday Inn across the street, though John Rubinstein was among a few who got to stay—along with Bob Fosse, Stuart Ostrow, Stephen Schwartz, and Roger Hirson—at the swanky Watergate Hotel, not yet known as the site of a national scandal. Rubinstein brought his wife and baby daughter, Jessica, who learned to crawl there. “We had a beautiful view of the Potomac River and would watch the rowers practice their team sculling,” he says.

Everyone had been following the ongoing debacle in Vietnam. The three television networks all had news teams stationed in the field, Rubinstein recalls, documenting “the explosions, the saturation bombings, the jungle ambushes, the helicopter raids, the assassinations of Vietnamese civilians, the burning of villages, the napalming of children, and, importantly, the dead and wounded American servicemen and women as they were loaded onto Hueys and Air Force cargo planes and sent to hospitals, and as they arrived back home.” The Pentagon Papers had been released just over a year before Pippin started rehearsals, revealing how the American people and even members of Congress had been deceived by government leaders over several administrations. Now the Pippin team was in the belly of the beast at which the show took aim—if not directly or consistently, then with graphic detail.

Like Schwartz, Rubinstein had demonstrated against the war and been haunted by the prospect of getting drafted. He got a medical deferment after graduating from UCLA in 1968, but by the time a lottery was instituted toward the end of the following year, he was assigned a number “in the lower middle,” making him more likely to be called than those with higher numbers. But he never was. “I lived in trepidation for years, but I was lucky.” Ben Vereen, who had a wife and young children, was excused from service, though he had joined Jane Fonda on a tour of U.S. army bases the previous fall—“to protest the war, not the soldiers,” he stresses. Richard Korthaze and Gene Foote had aged out of eligibility. “I was drafted for Korea,” Foote says, “but they asked me if I was a homosexual, and I said yes. Then they asked if I was passive or aggressive, and I said, ‘Whatever turns you on.’ And they told me to go home. By the time Vietnam came along, I was already an old lady.”

Candy Brown recalls, “There was this program where you could get a bracelet with a soldier’s name on it, and I got one. And even though we weren’t supposed to wear jewelry onstage, I wore that bracelet, and nobody said anything. So yeah, the war was very much at the forefront of everybody’s mind, though we had no idea that Watergate was going down.” Foote, however, is certain he saw a woman in a nightgown outside the hotel one evening, “running around like a crazy lady” and bearing an uncanny resemblance to Martha Mitchell, the soon-to-be former wife of Nixon’s attorney general, John N. Mitchell, who would be convicted and imprisoned for his role in the Watergate scandal. (Mrs. Mitchell had been known to speak openly and critically about the Nixon administration, and she would claim that shortly after the break-in, she was held against her will in a California hotel room to keep her quiet.)

A more bracing sign of the times was the bomb scare that interrupted a rehearsal of, wouldn’t you know it, “War Is a Science.” Foote recounts it most vividly: “We were working on one of the four variations we had already learned; Bob still wasn’t happy yet so we were doing a new version almost nightly. Leland Palmer had done nothing all day and was asleep in a box in the corner of the rehearsal room when someone burst in to tell us there was a bomb in the building. We all started to run when Bob said, ‘Wait, before we go, could we just try this one more time?’ Of course, the answer was no; Phil [Friedman] said we had to go. So we left the building and went out onto the lawn—and as soon as we were there Bob wanted to try one more thing. He didn’t want to stop working!”

It was a false alarm, happily, and far from the most anxiety-producing development during Pippin’s four-week run at the Opera House. A man that Jennifer Nairn-Smith had been dating had apparently learned of her involvement with Fosse, and was not pleased. There were threats of violence, according to cast members. “We had all heard and shared rumors about it,” Rubinstein says of the affair between the stunning dancer and her director, “but I personally never saw any evidence of it”—not until just before the trip to Washington, when the cast and crew moved rehearsals from Variety Arts to the Ethel Barrymore Theatre for a few rehearsals. When Rubinstein showed up for work, “Bob had bodyguards on both sides of him as he sat in the house, watching rehearsals”—Ostrow had hired a pair of off-duty police officers after learning of the boyfriend—“and we were frisked as we came in.” The backstage drama followed Fosse out of town. “They had to get a limousine to get Bob out of the Kennedy Center safely, because there were actual threats to his life,” says Cheryl Clark. In his memoir, Ostrow recalled, “I had to ask my connection at the White House to have the Secret Service escort us to the D.C. city limits.”

If Schwartz encountered no such dangers while in Washington, he was “not a happy camper,” according to Dean Pitchford, an actor and songwriter who met Schwartz when he successfully auditioned for a replacement spot in Godspell’s Off-Broadway cast, then served as standby for and eventually played Pippin on Broadway. Pitchford, who would become an Oscar-winning songwriter and screenwriter—his many credits include Fame and Footloose, as well as a musical theatre adaptation of Carrie—had been promoted to the role of Jesus on a national tour of Godspell that wound up spending two and half years in Washington, during which Pippin came to town. With Fosse firmly in charge of the latter show, Schwartz began spending some of his ample downtime with the Godspell cast at the Ford’s Theatre. “They were all my age, and friends,” he says. “It was sort of like, when you have a difficult family life, you go off with friends.”

Pitchford, who has remained close to Schwartz, recalls that the composer even began taking notes and calling rehearsals, perhaps trying to unleash his pent-up creative energy in a more welcoming environment. “We were all very happy to see him, but it got exhausting,” Pitchford says, laughing. “We were already doing a lot of extra stuff, making special appearances at schools and meeting people on Capitol Hill as part of publicity. So I had dinner with Stephen after the show one night, and I told him, ‘We love you madly, but you can’t keep rehearsing us. Just come and hang out with us.’ So he got in the habit of coming towards the end of the show, and then four or five of us would go to Georgetown and get Italian food. Then he’d call and ask me to have lunch, and I’d hear about what was going on at Pippin. He was feeling like the show had gotten away from him. Bobby, as I would eventually witness myself, endeared himself to the cast so much that he could do no wrong. Whenever there was a dust-up, everyone would line up behind Bobby—and Stephen was left feeling very alone. He had a strong relationship with John Rubinstein, but that’s because when Bobby was working with his dancers, John was sidelined; he would sit with Stephen while Bobby was working with Ben Vereen and Leland Palmer, who spoke the language he spoke.”

While Schwartz, again, didn’t feel that the dancers regarded him with any hostility—“Everybody was pretty nice to me, as I remember it,” he says—his strained relationship with Fosse complicated this late and crucial phase of the production. The composer doesn’t recall even discussing politics with the director, however much their mutual opposition to the war in Vietnam—and war generally—informed Pippin. Schwartz would be invited to visit the White House by Frank Gannon, an aide to President Nixon and a fan of both Godspell and Pippin. He accepted the offer but arrived wearing a button endorsing George McGovern, Nixon’s Democratic opponent in that year’s upcoming election. “It didn’t occur to me that was rude,” Schwartz insists. “Then someone told me that either H.R. Haldeman or John Ehrlichmann”—Nixon’s White House chief of staff and domestic affairs adviser, respectively—“was also a fan. That was both intriguing and horrifying to me—because I was so rabidly anti-Nixon, and I was learning that his henchmen were fans.”

Schwartz’s idealism was still fervent enough to make him chafe at an exchange during the scene in which Pippin, having killed Charles, briefly replaces him as king. “Pippin is trying to do all these good things that people are demanding of him, but they don’t work, and he winds up going back to basically ruling like his father.” Schwartz points to a line that he thinks Hirson wrote while working with Fosse—“Take that man away and hang him!”—echoing Charlemagne in an early encounter with one of his lowly subjects. “I know the scene works as shorthand, but it was very troubling to me politically—because it said, well, there’s no such thing as an enlightened ruler; you can’t change things. That was not a message I wanted to put out there at the time, and to tell you the truth, it still bothers me a bit politically. However, I have to admit that, as I have with several of the lines Bob added, I’ve come to like the line, because Charles says it in his first scene—and then when Pippin as king repeats it, Roger added a response from the unfortunate man: ‘Not again,’ which is funny and has the quirky quality I like about Roger’s work.”

Schwartz had greatly enjoyed crafting what may be Pippin’s most unabashedly sardonic song: “Spread a Little Sunshine”—a saccharine-soaked waltz sung by Fastrada in the scene where she learns of Pippin’s plan to kill his father and deceives both men in the hopes that she and Lewis will benefit. The song was crafted during rehearsals and became one of the composer’s happier collaborations with Fosse. Another was “Love Song,” which Schwartz wrote in Washington to replace “Just Between the Two of Us,” a duet for Pippin and Catherine that, according to Rubinstein, “was a perfectly nice song, but somehow didn’t grab the audience.” It also tested Jill Clayburgh’s limited vocal range. The romantic leads were called into a hotel room to read and learn the new song and immediately loved it. “We were delirious,” Rubinstein remembers.

Alas, their delirium would be too obvious that evening when they had to perform “Two of Us” once more for a live audience. “We ran onstage for the scene”—in which Pippin and Catherine first make love—“and she sat on her little square box that came out of the floor, and I sat next to her, leaning my arm in her lap, and I sang my first line and she sang her first line. But having just heard this new song, and knowing that it was being orchestrated and would go into the show in a night or two, we looked up at each other for the third line—and broke into hysterical laughter. Because we knew this old song was going away—it was halfway in the garbage—and we no longer had to give it respect or decorum, and our discipline just disappeared. And seeing each other laugh made us laugh harder. I remember looking at Stanley Lebowsky, the conductor, who was conducting nothing, just soft accompaniment to this song we weren’t singing. We sang about four per cent of it, maybe. And at the end, oh, were we sweating. That was one of the most shameful moments I have ever had onstage.”

Elysa Gardner has written about theatre and music for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, The Village Voice, Town & Country, Rolling Stone, Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, and USA Today, among other publications, and has been a contributor to VH1 and NPR. She is a theatre critic for The New York Sun and New York Stage Review, and hosts the podcast Stage Door Sessions for Broadway Direct.