In July 1967, a Black cab driver was brutally beaten by two white police officers over a minor traffic violation in the city of Newark, N.J. In the days following, violence and upheaval erupted in Newark and in cities across the United States where similar altercations between police and Black communities arose. Newspapers of the time, and historians today, describe it as “the long, hot summer of 1967.” But the history books may leave out other cities that felt the heat of that time a few miles away.

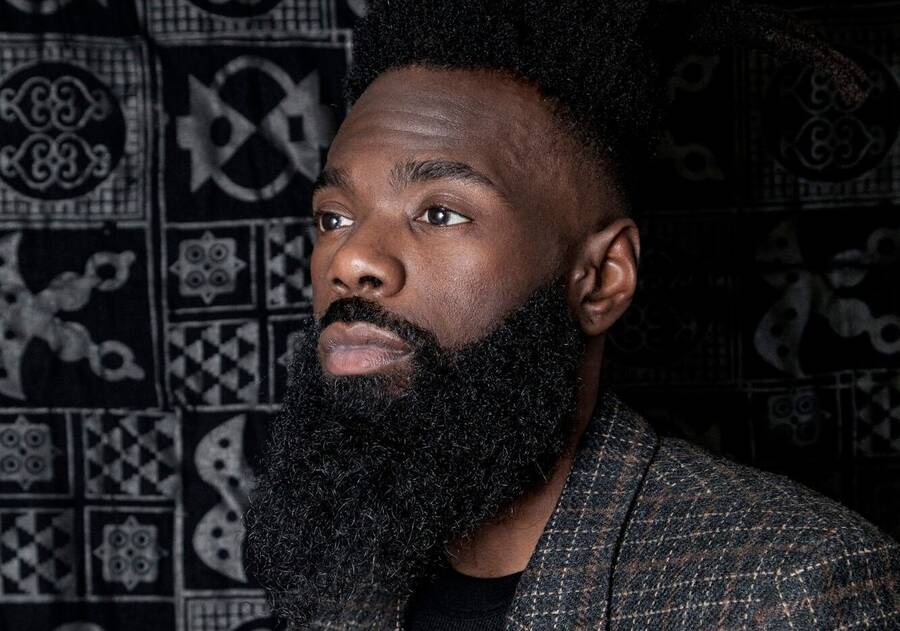

Plainfield, N.J., just 20 miles outside of Newark, is one such overlooked metropolis. It too felt the aftershocks of violence in the summer of 1967, but the ways that violence affected Plainfield, and more specifically how it affected the people communities like it, has not been widely recorded. TyLie Shider, an investigative journalist turned playwright, has made it his mission to recover lost and unreported narratives and adapt them for the stage. One of his plays, Certain Aspects of Conflict in the Negro Family, was staged Oct. 13-23 by Premiere Stages at Kean University in Union, N.J.; another, The Gospel Woman, is having a workshop production by the National Black Theatre at the Chelsea Factory in New York City, Nov. 9-13.

Certain Aspects of Conflict in the Negro Family is set during summer 1967 in Plainfield. It is the first installment of what Shider refers to as his “Mom and Pop” series, in which he sets out to illustrate how Black families coped with the violence and friction that occurred during and after the Civil Rights Movement. The play also serves as a love letter to his hometown; while Shider surely captures the city’s turbulence, he also affectionately establishes community members’ love for one another. But to arrive at a factual story, Shider had to do a lot of digging.

In a talkback held after a performance of Certain Aspects at Premiere Stages, Shider spoke about play, which was a result of a Liberty Live Commission to write a play about an event from New Jersey history. Shider said he began his research with the people who inspired his creativity: his family.

“I start with biography, because naturally my fixation with oral history started by listening to my parents and grandparents who tell stories,” Shider said. “Their stories always grip me because they are told with such conviction.”

Shider recalled how quickly his pen moved as he wrote the play’s first scene. “I was really channeling the rhythm of my maternal grandparents,” he said. “And so it was really easy for me to get that banter, that back and forth, that I would hear that they had at dinner or at a church event. I think it was really that rhythm, that syntax, that really broke ground for me and helped me to really get into the blood.”

That opening scene depicts two characters, Peach and Cliff, an estranged couple contemplating whether or not to return to the South. They settled in Plainfield after the Great Migration, the movement that resulted in Black Americans moving to Northern cities in search of opportunities and to escape the clutches of the Jim Crow South. Many of these families, though, faced restrictive redlining and police aggression in the North. Shider’s play manages to depict this history without making you feel as if you are sitting in a classroom.

Those stories not only offer a history lesson; they also strike a familiar chord. In showing the generation gap between parents and children—i.e., a father who doesn’t understand the next generation’s music taste, or a mother not fond of her daughter’s natural hair—Certain Aspects of Conflict of the Negro Family gave me some déjà vu of similar kitchen table conversations with my own family.

Considering that the show played in Union, just over 10 miles from where the story was set, I asked Shider how audiences received it. He told me that on closing night, an elderly patron complimented his storytelling accuracy; he himself grew up in Plainfield and could recall witnessing these riots when he was just nine years old. Praise for accuracy is one thing—Shider’s bachelor’s degree is in journalism from Delaware State University—but in writing for the stage he was after something more.

“I really am interested in concretizing the stories of others,” he said. “And my writing has always been focused on the other. Not in the sense of ‘other,’ like outcasts, but I’ve always been interested in using my gift to shine a light on someone’s story. Again, that’s the investigative sensibility that continues to drive my writing.” (His MFA is in dramatic playwriting from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts.)

His play The Gospel Woman tells another story that grew out of his own life. Set in 1972, it follows two sisters at odds who must find a way to maintain their ailing father’s Baptist church. The story is inspired by his mother and aunts, who built their careers as gospel artists. Shider said he has vivid childhood memories sitting backstage at concerts and rehearsal studios, watching his family perform.

In addition to the familial oral history that is omnipresent in Shider’s work, music also influences and carries both of his works. This is the sweetest part of the love letter that he writes to the city of Plainfield. Certain Aspects of Conflict of the Negro Family uses original music his family recorded during the ’60s and ’70s, weaving it through the play as transitions and to help portray the mood of the characters and period.

Shider doesn’t just write about his hometown, though. His earlier docudrama Whittier, which also made use of his investigative skills, tells the stories of a diverse group of citizens living in Whittier, a neighborhood of Minneapolis, in the days after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Shider wrote the show while working as an inaugural fellow of the residency program at ArtYard in Frenchtown, N.J. Whittier was inspired by the graffiti, lawn signs, and murals created in Minneapolis in protest of, and in mourning for, George Floyd’s murder. The play’s text is based on the words of focus groups, interviews, and talks that Shider conducted with neighbors, small business owners, and community leaders of faith during the 2020 uprisings in the neighborhood.

In all his work, Shider shows that by combining his investigative and dramaturgical skills, he can shed light on something necessary and integral to America’s unfolding history, whether it was 50 years ago just two years past. He is quickly establishing a playwriting career as the voice of the voiceless, and showing us that if you look a little more closely, the stories we are searching for are sometimes hidden right in our own backyards, or over our kitchen table.

Rachelle Legrand (she/her) is an editorial contributor to American Theatre.

This piece originally had the wrong dates for the run of Certain Aspects of Conflict in the Negro Family at Premiere Stages.