The last time I had spoken to Tim Robbins, the actor, director, and Actors’ Gang co-founder, was on Sept. 10, 2001, in a dressing room at the Gang’s old digs on Santa Monica Blvd. in Hollywood. I had lots of questions about what was then a divisive time for the then-20-year-old troupe, but what I most remember is that I made the mistake of mentioning the Gang’s co-production with Cornerstone Theater of Medea/Macbeth/Cinderella. He stared at me blankly for a moment, having heard the name of the Scottish play spoken inside a theatre, then insisted we go through a ritual of purging that involved me stepping outside the theatre building and turning around a few times; a pinch of salt might have been tossed over a shoulder.

As far as I know, the purging ritual worked and my gaffe led to nothing untoward in the runs of the Gang’s repertory productions of The Seagull and Mephisto, then in rehearsal as we spoke (though I do recall that Juliet Landau, of Buffy fame, was very suddenly replaced before opening in the role of Nina by Melanie Lora). The shows were of course postponed a bit, in part because Robbins, whose family was based in his native New York City, spent the next days and weeks there in the uncertain immediate aftermath of 9/11.

In the intervening decades, the Gang has had plenty of turnover in its membership and has relocated to the Ivy Substation in Culver City, but through it all Robbins has remained at the helm of this sui generis acting ensemble, whose aesthetic over the years has encompassed everything from Joint Stock-style devised theatre to commedia dell’arte, from Shakespeare to queer performance art, Living Newspaper commentary to Greek tragedy. But it all remains grounded in Georges Bigot’s commedia-inflected “Style,” which the Gang still offers classes in, and which informs all their work, even when they tour Shakespeare around the world or do work in California prisons.

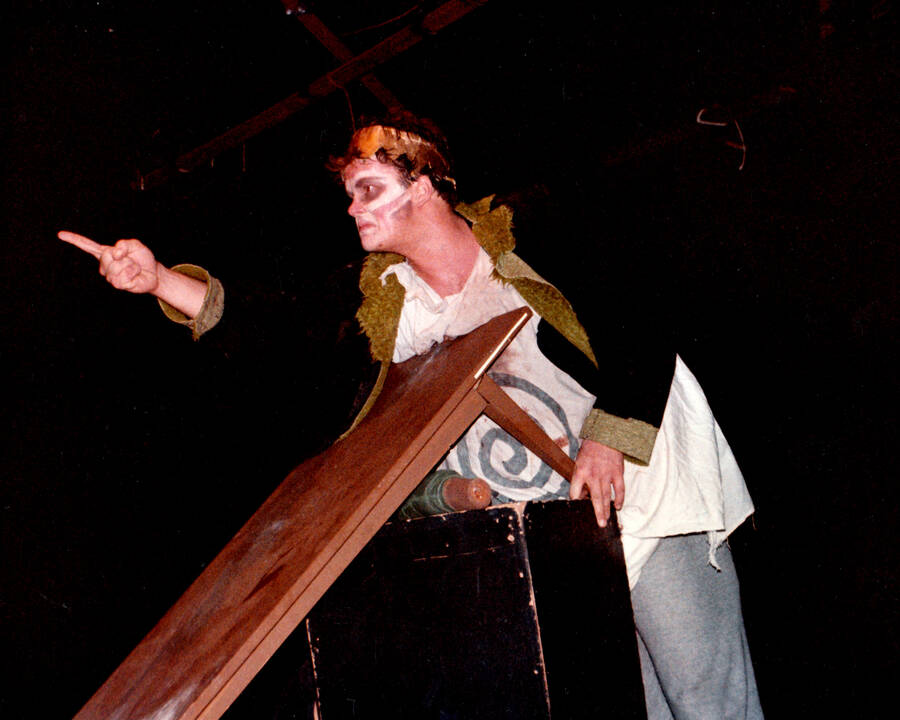

Now running at the theatre through Nov. 19 is a 40th anniversary production of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu The King. It was this proto-absurdist classic that launched the Gang back in 1982, when Robbins and a bunch of other young folks fresh out of UCLA’s theatre department staged it in at a ratty former tire shop on Santa Monica Blvd. He both starred in and directed that production, but is only directing the new one. The Gang has come a long way since its scrappy punk-rock beginnings, as has Robbins, whose film career took off in the late 1980s and has helped to bankroll the company’s efforts through many ups and downs. I spoke to Robbins a few weeks ago, while Ubu was still in rehearsals, about how he has maintained the Gang’s unique ethos and aesthetic, about the meaning and salience of Ubu’s attack on senseless authority, and the kind of audience he loves most.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: The last time I spoke to you was Sept. 10, 2001, and I made the mistake of saying the name of the Scottish play in your theatre.

TIM ROBBINS: Are you saying you caused 9/11? That’s some stunning ambition. You know, during Cradle Will Rock, Vanessa Redgrave said it while we were filming in a theatre, and she was like, “Oh, come on, that’s nonsense. I’m not going to go outside of the theatre and throw salt over my shoulder.” And then about 10 minutes later, one of the camera people sprained their ankle, and then there was a problem with this long take we were doing, some technical fuck-up. And we finally said, “Listen, Vanessa…”

Well, I won’t say its name again now, just to be safe. But the Scottish play is one of the templates for Ubu, isn’t that right?

Well, I mean, it’s a parody of it, and there’s some Julius Caesar in there.

I didn’t see that original production, so take me back: Why did you pick this play as your inaugural effort?

We learned about it in theatre history class. We had really cool teachers at UCLA at the time—younger professors that were not tenured yet and were telling us all about the darker side of theatre, the expressionists and the surrealists and the absurdists, and Ubu being kind of the ground zero of all that.

It was also the Reagan era then. What did you think the show was about then?

I had a pretty good handle on it. It’s about power. It’s about the unbridled id of the character Ubu as the expression of greed and lust for power. The reason I wanted to direct it was when I read the stage direction, “The entire Polish Army enters.” A little bit later: “A Palcontent explodes.” I said, you know what, I’ve got to figure out how to do that! It’s the bizarre nature of it. It’s just really funny, and it’s wrong. It’s incorrect in so many ways. It’s rude, it’s scatological, it’s inappropriate.

I was considering what to do this year for the 40th anniversary; we had many ideas, and we played with a couple of them. But this just seemed to make so much sense at this time; I feel like we’re living in a similar time to the one that we were living in when we started the Actors’ Gang. Also, I had done a screening for the company of the original production that we have on video, and all of my younger members were like, “We want to do this play.” So we did a workshop and it was like: Yeah, we gotta tear it up. We gotta get rude again.

Alfred Jarry was just 23 when he wrote the play, apparently basing Ubu on a teacher he and his colleagues mocked and despied. So there’s a sort of gleeful schoolboy attitude to it—like, he gives Ubu no redeeming qualities at all, he’s just the worst. You and your friends were about the same age when you first staged it. Revisiting it now at your age, does it feel like a different play, or is it still that youthful “fuck you” that it always was?

Oh, it still is definitely the “fuck you” it always was. But you’re right, there is no redeeming value to Ubu, and that’s one of the challenges about directing it, figuring out that. You know, you usually have something redeeming in even the worst characters, but he’s pretty awful all around. I guess the proof in the pudding is that rehearsals have been very funny. We’re having a blast.

I know that Miró later turned it into a puppet show, and it does have a sort of Punch and Judy quality. Do you feel like your actors are playing actual people, or are they playing this sort of weird cartoon version of humanity?

Oh, they’re definitely playing people. Everything has to be rooted in reality; even the strangest, most abstract pieces that we’ve done, we’ve had to root in a truth. I would find it impossible to do a play if it was all just artificial and cartoon. Even the great Warner Bros. cartoons are rooted in a truth. And you know, one of the influences in the original production was Warner Bros. cartoons—we wanted to see how we could do that onstage. But as far as the acting goes, the truth, the stakes, the emotions have to be sincere and they have to be real.

Going back to what you were saying about the Polish Army and the unstage-able stage directions, can you tell me a little bit about how you’re approaching it, particularly as compared to the 1982 production?

There’s a lot from the original production that we’ve retained, because it still works. It’ll benefit from the experience I’ve gathered over the past 40 years of pacing, clarity, and design, all that stuff. But there’s a lot that was very spot-on about the production in ’82, so we’ve been working off of that same stage design. One of the challenges, though, is that we originally did it in this dirtbag theatre, and we have a beautiful theatre now. We’re doing a similar thing to create atmosphere at the start—I’m not giving away what that is—but you know, this theatre that has a great sound system and a great lighting grid. It’s not the fly-by-night, make-cardboard-work situation you have when you’re young, when you’ve got to figure out how to do it with no money. We’re still keeping the budget way down, but we’re spending most of our money just paying actors.

I’ve seen pictures and read about the giant green phallus you swung around in the lead role in the original production as Ubu. What was that made of, and does your new Ubu have the same endowment?

It was made of canvas, and it was painted green, and it had a little clip on it so it could hook on. I’m making it less of a phallus this time and more of a sword. For various reasons. There are a couple things we did in the original production that…It’s interesting, when you’re portraying evil, you want to be courageous in how you do that, but at the same time, there’s a line that you cross that can make people uncomfortable. Discomfort is okay, but discomfort that has to do with trauma is not okay.

Right, I get it. A guy swinging a giant dick weapon around is not so funny anymore, if it ever was.

That, but also the way Pa Ubu talks to Ma Ubu. It’s like when you’re doing a translation of something, you pick one word over another, right? You always want to find out the original intent of the author, but being that this was written in 1898, there are certain societal things that have changed. And just as you would use a different word in some cases because meanings have changed, you might make a different choice because the original doesn’t get you anywhere; it doesn’t achieve the goal you want to achieve. In other words, something that was written in 1898 might not have been a trigger then, but is now. That’s the thing you have to look out for.

Right. I don’t know what translation you’re using, but the one I just read refers to a character being in blackface. I imagine you’re not doing that.

That’s Giron. Yeah, we didn’t do that back then either. That wasn’t in blackface, by the way; an African played the part originally, which must have been shocking to the Parisian audience—the one that rioted on the play’s opening day.

So I want to know more about the battle scenes and violence. Are you staging those as basically lazzi, or will there be some real blood and guts onstage?

There’s a decapitation, and there’s violence, but it’s all imagistic, it’s all expressionistic. It’s not realistic. I don’t want anyone to think someone’s actually getting murdered. But at the same time, I want to call attention to the amount of violence in our society that we accept, war being one great purveyor of violence that we seem to keep gravitating back toward as a solution to problems. Bordure talks about cleaving someone in two, and we do that. We also invented new ways of killing people, like a power drill to the head and a chainsaw through the body. But it’s all expressionistic. We also have a running body count. By the time the play is over, that chalkboard is full.

Going back to your beginnings, if the Gang started in ’82, that was two years before the Olympic Arts Festival in L.A. and your introduction to Georges Bigot, whose commedia-influenced Style you adopted as the Gang’s house style. So before you met Bigot, were you already doing a version of the style? Or did you see his work and think, “Oh, that’s another way to do what we are already doing”?

Exactly—that’s why we gravitated toward him, because what he gave was a discipline to the style we were already doing. It was all there: the use of the imagination, the use of mime to create a world without relying on props and set pieces. And what’s fun about Ubu is that when it’s at its best, it does feel like a bunch of kids playing in an inappropriate way. It has the anarchic spirit of the playground.

Well, it’s one thing to do that when you’re a kid, another to have a 40-year-old theatre company still doing it. I salute the fact that the Gang is still going at all, and doing so in Los Angeles, outside both the U.S. regional theatre system and outside the New York avant-garde or performance world. You have somehow maintained the Gang’s off-the-grid, not-a-joiner ethos, is that fair to say? I’m not necessarily asking you how you did it, but I do marvel at it a bit.

I did keep it together, but I wouldn’t have been able to keep it together without some extraordinarily talented people that were working with me, including Mike Schlitt, Brian Kulick, Tracy Young, Brent Hinkley, David Schweitzer. You know, Oskar Eustis did a play with us, Chuck Mee, Ellen McLaughlin. Incredible people have passed through the gate at the Gang. If I’ve done anything, it’s been that I’ve been the most stubborn about retaining an aesthetic, and to operate within that world, and not try to adopt a Broadway aesthetic. It’s heavily influenced by the work of theatre visionaries like Dario Fo, Peter Brook, Ariane Mnouchkine, Richard Schechner, Richard Foreman, Grotowski—the idea that theatre can be something more than what the commercial theatre has become.

My favorite audience is an audience of novices. One of my favorite pieces of art is a Ralph Steadman piece called “Seasoned First-Nighters and a First-Time Theatregoer,” where you see the faces of these jaded people watching a play and one person just laughing hysterically. I’ve always loved when we have been able to do pieces that bring in people to the theatre for the first time. That’s something that we have had from the start, attracting a different kind of audience, and then we have still been able to have great support from regular theatregoers as well.

I think part of our job as people that work in theatre is to understand something that Peter Brook was very eloquent about—this idea of being in the unknowing, to not be an expert, to be able to grow and learn and continue to test what you know with the dynamic of a live audience. The great thing about theatre, as opposed to cinema, is that it’s a constantly evolving chemistry that you have to figure out. To be able to perform a play one night and create magic and then to do it again the next night is the ultimate goal of people that work onstage. And with our training, we came to understand that you can’t do Thursday night’s show for Friday night’s audience; if you were trying to recreate something, you didn’t meet them and create the chemistry needed for that night. We have the unwritten rule: Don’t blame the audience. You figure out what it was you did that didn’t connect. With film you have the editing room, and you may test it in front of audiences and get feedback and cut it, but then it’s locked forever. With theatre, you always have this opportunity to create this magic, which is intoxicating. I think that’s the reason why people stay in it.

You said earlier that you felt this time is like the time in which you originally staged Ubu. Can you say more about that? Obviously, the play’s portrait of a slobbish authoritarian with a raging id is going to make some audiences think of Trump.

I think that’s valid to say, but I also think it goes way beyond that to our own natures. Listen, leaders will always lead us into nefarious situations, war being the most nefarious. Leaders are always going to try to stir shit up, and the way that people stay in power is to keep a potentially united public divided. When you have this happening on both the right and the left, you wonder where you belong. I don’t want to be in a group of people that are demonizing at least a third or half of this country. We’ve never approached the theatre we do that way—that only certain people can come into our theatre if they believe a certain thing. That’s the opposite of what a forum is. If you’re going to create effective storytelling, you have to invite everybody in the room.

One thing that’s changed since 1982: I notice on your web page for Ubu that it advises audiences to “Come stoned.”

Well, it was conceived by stoners back in ’82, back when it was illegal. Now that it’s legal, why not?

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org