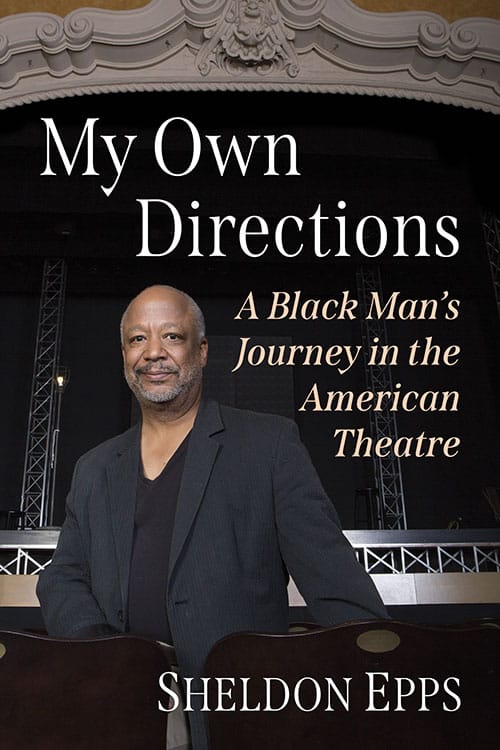

The following is a chapter from Sheldon Epps’s new memoir, My Own Directions: A Black Man’s Journey in the American Theatre. For a Q&A with Epps about this book and about his career, go here.

On this long, rewarding journey, there was certainly one road that was the most fulfilling and rewarding. It was also frustrating, exhausting, and sometimes surprisingly treacherous. It was full of tremendous highs and lows. The journey along that road was all about building a Great Theatre. Sounds like a fairly simple goal, doesn’t it? That is what I had in mind when I accepted the job as artistic director of the renowned Pasadena Playhouse in 1997. By that time I had worked on and off Broadway, on the West End in London and at many of the great theatres all over America, including the Guthrie in Minneapolis, Cleveland Playhouse, and Crossroads Theatre, and I had the benefit of my four-year stint as associate artistic director at the Old Globe theatre in San Diego. I later would refer to my time there as my graduate school education in what I call “The Art of being an Artistic Director”—and quite a good education it was! And blessedly, I had been watching great theatre at many great theaters in this country and all over the world for decades. So I had a pretty clear idea of what makes for theatre greatness.

Pasadena Playhouse had many of the essential elements in place when I got this calling: a long and illustrious history, a beautiful physical facility, and the theatre is located in greater Los Angeles, a dynamic city with an audience for good theatre and an appetite for good work—despite a strong reputation to the contrary. Many of the essentials were in place to achieve this lofty goal. So why not? Surely that’s something that could be achieved if I gave it, let’s say, a good five-year commitment. So why not? Two decades later, I was still pushing to make this dream a reality with great success, inevitable failures, highs and lows, tremendous rewards and reasons for pride, and most certainly never a week, month, or year in which there were not great challenges of all kinds with a scale from hardly noticeable to catastrophic! All of that was in the future. In the moment of decision about beginning this journey I had the liberty of dreaming of greatness. Any really good artist must of necessity also be a dreamer. So why not let the dream begin?

I did not come to the job strictly as a dreamer or without preparation. I’d had some very good role models who had generously prepared me for the job over the years. Certainly my recent graduate school training with Jack O’Brien, artistic director of the Old Globe, had been hugely valuable and informative. But I’d had some great mentors long before that. Going all the way back to my days as a young actor at the Alley Theatre in Houston, when Nina Vance, truly one of the pioneers of the resident theatre movement, would come into my dressing room and actually sit not just on, but in the sink and regale me with tales of the early days of establishing her theatre. Her stories, told with theatricality and great Southern charms, were both inspiring and often hysterical.

I was lucky enough to spend time with one of her compatriots and best friends, the brilliant Zelda Fichandler, founder of Arena Stage in the nation’s capital. Zelda was one of the only people I have ever known who could speak extemporaneously in perfect paragraphs—so just imagine how great her prepared and written speeches were. Zelda beguiled me with her own great stories of the founding of the movement. She was especially inspirational when she spoke of “the value” of the work that we do and how it can change our lives and our society. I met the leonine Lloyd Richards, a pioneering man of color in our field (most notably as the director of the first production of A Raisin in the Sun and later as partner to August Wilson in the development of his first plays) when he was head of Yale Repertory Theatre and the prestigious Yale School of Drama (now known as the David Geffen School of Drama at Yale). A man of few, but mostly brilliant and profound words, summed up so much for me when he advised me to “Keep your eyes on the prize, not on the prizes.” Thanks for that, Lloyd.

And in some ways most profoundly, Garland Wright, artistic director of the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis during one of many shining eras in the history of that prestigious theatre. In my brief but very full time there I was able to spend time in “the court of Garland,” as it was called, not by him, but rightfully so. This was at a moment in my journey when I started thinking about a life as an artistic director, probably subconsciously. Garland taught me many lessons about being a great one. Patience, trust, faith, staying out of the way until you are needed and then getting in the way (and knowing how to get in the way) when that is necessary. Also knowing that it is not always necessary—that’s the faith part. And vitally, he subtly taught me about having a vision for a theatre that included the artists, the audience, and the community, and putting equal value on all of those “partners in the endeavor,” as he called them. Garland was another fellow Scorpio who inspired me with his brilliant work and his brilliant words, which he was always careful not to characterize as advice. “Just a thought, do with it what you will,” he would say about small things or very big ones in his eloquent and dark-hued baritone voice. My sojourn at the Guthrie was brief, but oh so valuable to me. The lessons of these and many other giants in our field truly prepared me to be ready to run the theatre. I had a great deal to learn, to be sure. But these icons had given me a real head start and real lessons in how to think about creating a great theatre and finding your own way to be an artistic leader. Willingness to dream was a concept that they all shared, which gratefully they passed along to me.

The Pasadena Playhouse was founded in 1917 by another mad dreamer named Gilmor Brown. He came to Pasadena as a traveling player earlier in that century and fell in love with the small but vibrant community’s physical beauty, near perfect weather, and his own sense of the potential of the place. He started his theatre company in a tiny saloon in what is now called the Old Town area of the city. With great determination, drive, passion, and, we are told, a special penchant for charming the “Little Old Ladies from Pasadena,” he managed to build a beautiful first-class theatre for his company in 1925. This glorious palace of art was in the middle of an orange grove, several blocks from the center of town. Although its beginning was rather humble and certainly much more community theatre-based (in fact the original name of the theatre was Pasadena Community Playhouse), Gilmor managed to push the company into becoming one of the most successful and well-known theatres in the country. It attracted well-known actors and directors and premiered plays by some of the country’s most well-known authors. Several years into its life in the magnificent home that he built for the company, he charmed a few more of those little old ladies to build an adjoining five-story building which housed the Playhouse School for the Arts, which for many years was considered one of the best training programs for young actors in the country, helping to launch the careers of Robert Preston, Charles Bronson, Dana Andrews, Sally Struthers, Morgan Freeman, and even ZaSu Pitts. Many years later, two of the school’s students who trained there were given slim chances for success as actors. That would be Gene Hackman and Dustin Hoffman. A pity that their careers never went anywhere! That misjudgment aside, Gilmor Brown really did accomplish remarkable things at Pasadena Playhouse even before the regional theatre movement really took hold in the country.

Alas, one of his few failings was doing little succession planning. When he passed away, no one knew quite how he managed to keep the place afloat and where the bodies were buried (some say literally!). As a result, the theatre floundered for a few years after his death, and a bad combination of financial issues, lax artistic standards, and the slow diminution of the popularity of the school’s training program led to the theatre shuttering in 1968. The once beautiful theatre was basically gutted by creditors and went into great disrepair. Pictures of the state of the theater during this period suggest that a site-specific production of the musical Follies would have been very much at home there without touching a thing! Things got so bad that the theatre was nearly torn down in order to, as Joni Mitchell wrote, “Pave paradise and put up a parking lot.” Indeed, that exact thing very nearly happened. The building was very much on the verge of being leveled when a few brave souls staged a Norma Rae-like protest to stop the progress of the demolition crew. The efforts of this same passionate group eventually allowed the in-terrible-shape-but-still-standing structure to receive designation for being historically significant. Bulldozers stand down! The theatre was here to stay.

Sadly, however, the building did not spring quickly from that brave moment into new theatrical life. The theatre was boarded up and remained closed and sadly neglected for many years. There are some terrible photographs of what it looked like as the result of water damage from a leaky roof, lack of maintenance, and occasional vandalism. Finally, a gentleman from the real estate development business named David Houk came along and saved the day. Mr. Houk actually had very little interest in the theatre or the entertainment business. He was a developer. Based on research, he had come to learn that putting a theatre or a performing arts venue at the center of a dicey neighborhood would and often did increase the value of the blocks around the venue. David had a vision of getting the theatre reopened, buying up and developing the properties around the theatre, and populating the neighborhood with new construction of all kinds that would house residential properties, office space, restaurants, and retail possibilities. His idea, which was a sound one, never came to fruition during his time at the theatre. Ironically, what he had predicted and hoped for (and even drawn up on fully realized plans) was exactly what happened many years later, when the theatre would indeed be the centerpiece of what became known as a revitalized Playhouse District that gave the city great pride. He didn’t get all of that done, alas, but in collaboration with the city, he did rebuild, refresh, and reopen the theatre, and blessedly, based on historical photographs and plans, restored it to its original Spanish palace-style glory. He made some mistakes further down the road, but he should be well credited for that accomplishment. After a few fits and starts, Houk and Associates did get the theatre open and functioning once again. And actually, it was not long before they were producing with great success and once again being acknowledged as one of the more important of the larger theatres in the Los Angeles area.

I first directed at Pasadena Playhouse in 1991 at the invitation of Paul Lazarus, a longtime friend from my early producing days of running a small (really small) theatre in NYC called the Production Company. Paul, during his brief but exciting tenure as artistic director, asked me to direct a good old chestnut of a play called On Borrowed Time. It was during the preview period before the opening of that play that I got the call to come down to the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego to meet Jack O’Brien to direct a new play called Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting. That phone call eventually led to my graduate school matriculation during my four years at that theatre. During that time, I returned almost yearly to direct at Pasadena Playhouse and formed a good association with the current executive director, Lars Hansen, and many on the staff at the theatre. Sadly, my friend Paul left the company soon after my first production here. And not long after that, Mr. Houk himself exited the building, giving up his adventures in the theatre to return to real estate development. Lars Hansen, however, remained and soldiered on, running both the business and the creative operations of the company.

Lars was the person who invited me back to direct several times, and we formed a solid working relationship which shortly would lead to an unexpected and life-changing invitation. Many think that I made the decision to leave the Old Globe because I was offered the position at the Playhouse. That is not quite true. For a number of reasons, I knew that it was time to make a move after working under the auspices of a grant from Theatre Communicaions Group at the Old Globe. One reason was certainly that both the grant itself and the munificence of a two-year extension on that grant had been exhausted. The theatre would have been challenged to maintain a full-time salary for me without that outside support. And I would have been challenged to stay no matter what, given that I had hit a lovely but quite unbreakable glass ceiling at the company. So, I had to “Move On,” as Mr. Sondheim would say. After contemplating a renewed life as a gypsy freelance director back on the road once more, dreading the blank white walls of the guest artists’ housing, I had already made the decision to move “up North” to Los Angeles to further pursue a nascent career as a television director, hoping for financial security at last, if not complete artistic fulfillment. When he heard of my plans, I received a blissful invitation from Lars to work with him at Pasadena Playhouse as artistic director on a “half-time basis.” A bit of a strange construct, but, as I said, why not? Of course, this was never the case in truth. Especially as my opportunities began to take off in the land of television, which generously supported my theatre habit. I found myself in fact having two full-time careers. Challenging, to say the least, but I was young, strong, driven, and perhaps a little bit insane. So, once again, why not?

Over the course of the next many years there were many weeks when I would spend much of the day on the set of a television show and my late afternoons, evenings, and weekends at the theatre on El Molino Ave. building the theatre! It was challenging, rewarding, sometimes a bit reckless, and quite often exhausting. But somehow I made it work, both for me and, I believe, the theatre. My work in the television world fed my work at the theatre and in fact directly influenced the growth and expansion of Pasadena Playhouse, as I was able to bring artists, donors, and influencers into the life of the theatre as the result of my collaborations with many passionate theatre lovers who were now finding great success in other areas of entertainment. At a certain point the demands of the theatre, along with my own slackening energy for keeping all of the balls in the air, made this juggling act less possible, and I drifted away from doing television work (before it drifted away from me) in order to fully focus on running the theatre.

And focus on the theatre I did! I took supportive inspiration from those great men and women who had fought difficult but vitally important battles before me. I asked myself those time-honored and most valuable questions: If not me, then who? If not now, then when? I focused on this theater with the vision of building a great theatre, as I said. Did I ever actually achieve that goal? That is for others to say. But I do know that we had moments of greatness. Many of them. I do know that it was a far better and more highly respected theatre when I stepped down from my position after two decades than it was when I walked into the job with such high hopes and great expectations. I do know that it became a theatre that many recognized as first-class—a theatre to which “Attention must be paid!”

The next two decades of my life would be filled with making this happen, which would make for an often quite glamorous and starry journey. But it started like this….

Shortly after it was announced that I would be ascending to the throne as artistic director of the Playhouse, a very radical weekly newspaper in L.A. did a feature story praising the decision but predicting that the waters could be much less than smooth. The essay pointed to Pasadena’s long history of conservative politics and racial division. The writer expressed a combination of shock and awe that a Black man had been designated to take a leadership position at what was then widely thought to be “a white theatre.” The article, which made some quite salient points, predicted that my tenure at the theatre would not be tolerated by some and might very well be quite short. It predicted that the fair-skinned constituency of the theatre would find a way to make a transition in the near future (code for “get rid of me”) and take their theatre back! The well-written essay was accompanied by a startling and unsettling bit of artwork: an Al Hirschfeld–like drawing of me boiling in a pot of hot oil while wealthy conservative WASP types danced around the cauldron with spears and knives. When I saw the article and the drawing, I was somewhat agitated but also entertained by this aggressive way of depicting my new creative endeavor. When my mother saw it, she merely bowed her head and softly cried. Ever a loving and caring mama! The article, titled “Theatre of the Absurd,” began with this: “Sheldon Epps may be just the man to bring new flavors to Pasadena, a town known mostly for its vanilla.” And later, “Is Epps the man to satisfy the geezers, galvanize the hipsters, placate the board of directors and keep the closet racists at bay? If so, this Black artist leader in a racially complicated community has his work cut out for him.” So very true!

There were real reasons for concern. Or at the very least, consternation. The Playhouse was designed in the beautiful and appropriate Southwest mission style, and is fronted by a gracious courtyard with a majestic fountain. This commodious space serves as the theatre’s de facto lobby, given the gracious Southern California weather, which offers up balmy days and nights even in the depths of winter. As both a freelance director and then in the early days in my new position, I would frequently sit in that commodious courtyard as the audience gathered before a performance. It was all too often the case that I was the only person under 60 going into the theatre and, even more frightening, the only person of any color waiting for the theatrical event to begin. Both things struck me as fundamentally wrong on so many levels. Warning bells went off as I observed this day after day. This represented a great challenge for me and for the theatre from the artistic, the emotional, and even the business level. A great challenge for every theatre in America was an aging audience that might soon disappear if new audiences were not identified and wooed to fill the seats.

The theatre community was rife with rumors that this Black guy intended to turn the place into Negro Ensemble Company West and that the existing white audience would soon be running from the theatre in droves as I programmed one Black play or musical after another. No one who had paid any attention at all to my career or my vastly wide-ranging taste in material up to this point could have possibly believed that this was true. Nor would it be if I had any business savvy at all. I certainly recognized that the way to shake up this theatre and its audience was through the programming. And indeed I did want the support of all of the diverse communities in greater Los Angeles. I wanted that both artistically and emotionally. But would it be transformed into an all-Black theatre overnight? Not my aim, not my desire, and not my way to the exit door.

But things would indeed change. I believe that any good theatre is driven by the taste, passions, and artistic desires of its leaders, and that is as it should be. If you don’t believe in those qualities in an artistic leader, don’t hire that person! Yes, I wanted to produce plays and musicals by artists of color (of all colors, by the way), but I also had a well-demonstrated and healthy appetite for Tennessee Williams, Noël Coward, Cole Porter, and Shakespeare!

Here’s something to remember: One of the great things about growing up as a person of color in America is that you get to know “your own stuff” and your own culture, to be sure. But the well-kept secret is that, if one is smart, you also get to know theirs. Either by choice or necessity, you get to know everything about the white folks, but you also get to know everything from your own cultural experience. And that is not often a two-way street. So being a person of color is in this regard a benefit. I am forced to learn all that you white folks know, and I get to know all that comes out of the Black experience. It is very rare indeed that artists without pigmentation benefit from this equation. I certainly did.

I wanted to make great Art, to be sure. But as the Civil Rights icon John Lewis used to say, I also wanted to get up every morning to make “good trouble.” I set out to shake things up in a meaningful and necessary way because it was time for the work on the Playhouse stage, and on all of the stages of American theatres, to reflect the thrilling diversity, colors, and shape of America! So my very first seasons at the theatre did indeed include choices from the African American and Latino canon of dramatic literature, but mixed in with works by Tom Stoppard, Noël Coward, Moss Hart, David Hare, and many others.

These choices were rarely commented on in polite Pasadena society, but there were certainly questions in the air. Would long-term subscribers sit still for such a wide-ranging program, or would they be made uncomfortable by seeing artists of color on the stage and hopefully in increasing numbers in the audience? Would this chase some people out of the theatre? Probably. And my firm belief was that it was best to let them go. Running out, I hoped, never to return again, if journeying to a world that was different from their own was too much for their delicate sensibilities. Let ’em go!

I firmly believed, and it certainly turned out to be true, that the small number who would go running away would be valuably replaced in much greater numbers by those who would embrace the magic of diversity on the stage and throughout the building.

Did I know that for sure? I did not. Remember that this was well before diversity, the “D” word, became ever so prevalent at major arts institutions. In fact, Pasadena Playhouse was something of a pioneer in this fight. I was taking a chance, yes. But it was more a leap of faith. And one that paid off with rich rewards for the theatre in every way. Artistically, culturally, aesthetically, and quite frankly at the box office.

Over the next several seasons the shows that rose to the top of the sales charts were those that had appeal to audiences of color. Clearly they were eager to be served up good meals from their own cultures, their own stories, and their own experiences. I was happy to do the serving. And even more happy, in fact proud, to say that this new approach to programming was by and large not only embraced but indeed celebrated by the existing audience at the theatre even as it attracted thousands of new theatergoers of all colors into our house. Those “Little Old Ladies from Pasadena” may have been a bit nervous or even shocked at the very beginning, I suspect. But many of them became my most ardent and loyal supporters.

But before any of the highs or any of the lows, before I had a chance to make a theatre great, or even try to accomplish that noble goal, there were just questions about how I got there. How did I get myself placed in that cauldron of boiling oil, daring to bring literal and figurative color to an institution which was so proud of its whiteness? How did this man of color dare to ascend to the leadership of this conservative bastion of art and culture in what was one of the most conservative and still racially divided communities in America?

Others asked those questions, and other questions that I have often asked myself, to be honest. Over the course of a long and rewarding career, exactly how did I get into so many of “the rooms where it happened” even before I got to Pasadena Playhouse? How did I manage to stand on the stages of Broadway and the West End theatres? How did I manage to travel through my work to so many mysterious and enchanted places, including what they call “The Lots” of Hollywood, where I would look up to that famous sign on the side of the hill? As I made my way to and from stages that had been filled years before by the major stars of the stage and screen, and as I shared rehearsal rooms with some of the legends and brightest lights in the entertainment world, there were many moments when it hit me with a kind of blinding reality that creates both tremendous humility and overwhelming gratitude.

Somehow I was actually there. But how did that happen? How did I get from the south side of Los Angeles—the “colored” part of town—to all of those rooms and all of those stages? How did I make my way into the executive office of one of the most illustrious theatres in America as its artistic director for two decades? Especially at a time when it was all too rare for a person of color to have such an exalted position? How did I get the chance to work with some of the greatest actors, directors, writers, and producers of our time both here in this country and all over the world? How did all of that happen?

As I began my long tenure at Pasadena Playhouse and set out to make it a great theatre, those questions lingered in the air, in the press, and, to be quite honest, even in my own mind. How did all of this happen? After all, I was just a kid from Compton….

Sheldon Epps served as the artistic director of the Pasadena Playhouse from 1997 to 2017.