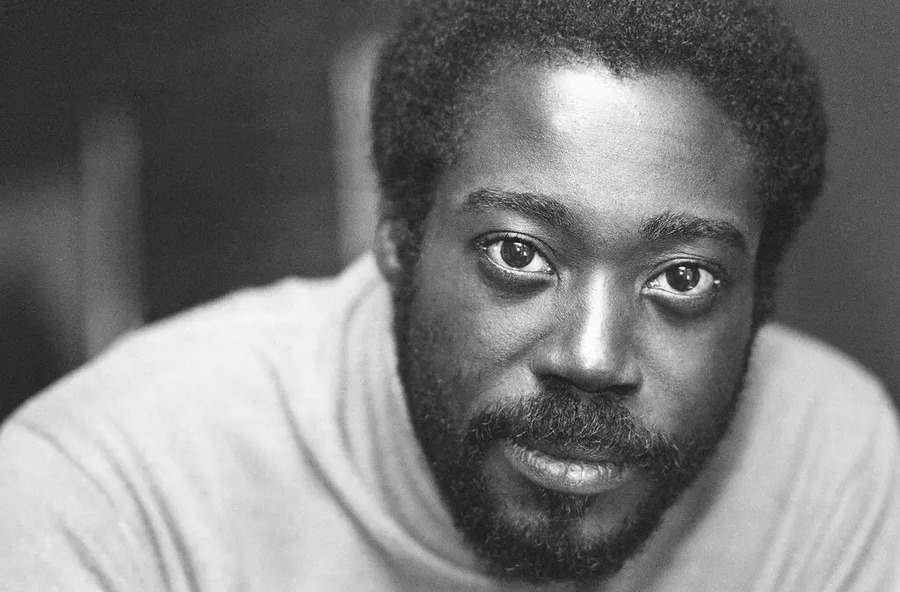

Charles Henry Fuller Jr., Obie, Tony, and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, Oscar-nominated screenwriter, and co-founder of the Afro-American Arts Theatre in Philadelphia, died on Oct. 3. He was 83.

A Remembrance

During the rehearsal process of the Negro Ensemble Company’s premiere production of A Soldier’s Play at Theatre Four in New York City, (I was the production supervisor-stage manager), I was attentive as Charles and Doug often discussed the ending of the play throughout a truly short, intense, but at the same time, relaxed rehearsal process. At the end of the final run-through prior to the first preview, recalling their conversations, I realized that the issue of the ending of the play had not been resolved.

The cast took their dinner break. I asked Charles Brown (Captain Davenport) and Peter Friedman (Captain Taylor) to return to the theatre a half hour earlier. Doug had told me he and Charles would be at the NEC office in the Equity Building of 46th Street and 7th Avenue. I called the office and told the receptionist to put me through to Doug immediately. I told him “I was on my way there. Do not leave! Charles and you never resolved the ending of the play!” After a beat of silence, I heard, “Oh sh**!”

I grabbed the production book from the stage manager’s desk and ran from the theatre to the office—rush hour had started—it was faster than taking a cab. When I arrived, I called Charles and Doug into my office. I reminded them that the final line of Davenport’s monologue was the last line of the play: “The men of the 221st Chemical Smoke Generating Company? The entire outfit: officers

and enlisted men were wiped out in the Ruhr Valley during a German advance.”

Charles and Doug had a passionate discussion about the implications of that line being the end of the play.

“Now what?”, I asked, looking at Charles and Doug. I put a piece of paper into the IBM Selectric typewriter and waited, fingers poised on the home keys. Doug lit another cigarette. Ironically, he was already smoking one. He looked at Charles. Charles began dictating the final scene. I typed rapidly, fingers flying. Doug nodded, puffed, and grunted, offering a suggestion here and there. I told Charles and Doug to come to the theatre in thirty minutes, and ran back to the theatre, copies of the new scene in hand. I gave Charles and Peter the new ending of the play and told them to “Memorize it now! Doug and Charles are coming over to block the scene and answer any questions.” Thank the powers that be Charles Brown and Peter Friedman were very quick studies. They memorized the scene. Doug staged it. We integrated the technical aspects. Charles Fuller approved, and the rest is history . . .

TAYLOR

I was wrong, Davenport – about the bars – the uniform – about Negroes

being in charge.

(Slight pause.)

I’ll guess I’ll have to get used to it.

DAVENPORT

Oh, you’ll get used to it –you can bet your ass on that. Captain – you will

get used to it.

THE END

In the lobby of Theatre Four after the first preview performance of A Soldier’s Play., Charles pulled me aside and said “Thank you for remembering. I owe you.” In 2013, Charles requested me to direct his new play, One Night—a co-production between The Cherry Lane and Rattlestick Playwrights Theatre companies. A dark and disturbing work about sexual assault and PTSD in the military, Charles was quietly very passionate about the play and its importance.

I shared stimulating dinner conversation after an early preview performance of One Night with Charles, Claire (his wife), and the late Paul Carter Harrison who was visiting NYC from Panama. Paul was a longtime friend and colleague of Charles. He was also my former professor at Howard University, additionally, I had production supervised or directed several of his plays at the Negro Ensemble Company. We all talked about the state of the world, the state of black art, and eventually One Night. Through a very concise and stimulating analysis of the play among all of us, Charles realized that the play would be stronger as an extended one-act as opposed to the two-act structure we were currently previewing. We instituted the necessary changes in the following rehearsals and previews. The play opened as an extended one-act and was consequently a much stronger play. I will always be humbled by Charles’ openness and willingness to engage in the collaborative process and place his trust in me as a director of his work. The reunion and renewal of friendship throughout the realization of One Night, conjure memories of conversations about African Americans in the military—a significant trope in his body of work. He often referenced The Brownsville Raid and A Soldier’s Play, but he never spoke of his own military service. I respected his choice.

Charles knew the language of actors and directors. We frequently spoke about the passion required by actors to access that hidden spine of a character. Remembering and witnessing conversations he had with a very young Giancarlo Esposito, as well as with veteran actress Mary Alice, Charles helped them tap into that passion, enabling them to give startling, revelatory, and fearsome performances in Zooman and the Sign.

As more memories continue to flood my mind, I take comfort in knowing that I walked with an artistic giant. Charles was a dear friend, and collaborator, who touched multitudes. I smile as I imagine the Ancestors greeting Charles Henry Fuller, Jr. with shouts of “Well Done! My Brother! Well Done!”

Clinton Turner Davis (he/him) is a director, educator, dramaturg, playwright, production supervisor, and arts consultant. He was the production supervisor of the original NEC production of A Soldier’s Play, and its subsequent 22-month national tour. Mr. Davis also directed the first NYC revival of A Soldier’s Play for the Valiant Theatre in 1996.