Robert Kalfin, founder of the Chelsea Theater Center and longtime Off-Broadway producer and director, died on Sept. 20. He was 89. Another tribute to him and his legacy can be read here.

In the mid-1960s, increasing costs made it hard for once-thriving commercial Off-Broadway theatres to thrive. Meanwhile money, private and public, was flowing to resident theatres across the country. Robert Kalfin thought: Why not start a nonprofit theatre in New York?

So he did, in two successive churches in Chelsea from which his company was quickly booted. Was he discouraged? No. Throughout his career, when something went wrong, Kalfin would try something else. That’s how the Chelsea Theater Center became the resident theatre company at Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) in 1968. Critics raved about Chelsea’s work, and audiences began to subscribe before they knew what plays Chelsea would do next season.

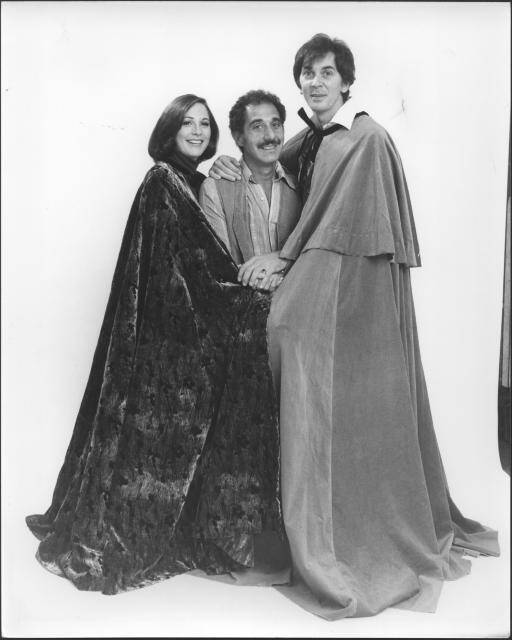

Kalfin and two new partners he had met at Yale, where he was teaching, took pride in doing “plays nobody else would do.” They reimagined little-known classics as well as new plays, all of them works that questioned assumptions. Kalfin directed plays based on poems, on Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, on Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Yentl the Yeshiva Boy. Believing, as he once put it, that “theatre reflects shared universal experiences,” he routinely brought artists from different backgrounds into the same projects.

With executive director Michael David, now of Dodger Properties, and production manager Burl Hash, Kalfin produced some of the first multimedia and environmental productions. He brought exciting directors to Brooklyn, including John Hirsch, artistic director at the Stratford Festival; Carl Weber, who had assisted Brecht at the Berliner Ensemble; and Des McAnuff, who directed his first New York show at Chelsea. Kalfin even lured Hal Prince to Brooklyn to stage an environmental revival of a show that had originally flopped on Broadway, Candide.

Kalfin was born in the Bronx on April 22, 1933, to a Jewish couple of Russian descent. He was culturally Jewish and gay, but he refused to define himself in a way that excluded him from a category he wasn’t in, aiming to transcend limits and communicate across barriers. He set out to produce plays about Native Americans, Black Americans, women, and, yes, Jewish people and gay men.

He sometimes clashed with others who did define themselves by their culture—for instance, Chelsea ceased production on Dawn Song, a play about Chief Joseph, when members of the Nez Perce tribe protested its casting of white folks in Native roles. A man of ideas and ideals in a pragmatic society, he clashed over money matters with some, including his own executive director, Michael David.

Actors loved him. Kalfin urged them to take big risks and trust their instincts. He would try staging and interpretations he knew might fail so that actors would feel free to take big chances, even make terrible choices—that vulnerability, he knew, was the path to great choices. In his last years, he was working on a book about directing he called Making it Safe to be Unsafe.

Frank Langella phoned Bob when he heard Chelsea was going to do The Prince of Homburg and asked for the role. “I always wanted to do The Prince,” he said, “and I wouldn’t do it with anyone but Bob.” When the limited run was over, he arranged for PBS to record it for its series Theater in America.

Christopher Lloyd’s first big part in New York was in Kaspar, in Weber’s production of Peter Handke’s play. Previews weren’t going well, and he felt stuck until Bob reminded him of the fun he initially had with the role. “I put the fun back into it. Bob saved the day,” he said. He later appeared in Bob’s productions of Total Eclipse and Happy End (opposite Meryl Streep).

Glenn Close, who appeared in McAnuff’s production of The Crazy Locomotive, wrote to recall “Bob’s laughter, enthusiasm, and intensity. He made us all feel special and a part of something important.”

Marilyn Chris, who won an Obie, Drama Desk, and Outer Critics Circle Award for the lead role in Kaddish, had worked with Kalfin before the Chelsea years and after. A close friend, she took him to doctor’s appointments in his last year. “Robert loved actors and was a joy to work with,” she recalled. “He had a remarkable humility. He believed it was his fault if you couldn’t do something. That made you feel so much less guilty that you wound up doing it after all. I sorely miss him.”

Kalfin didn’t hold grudges when an actor didn’t see things his way, and the feeling was mutual. “We collaborated brilliantly on Yentl,” said Tovah Feldshuh, who would ultimately be nominated for a Tony for the role when the show transferred to Broadway. Acknowledging a few hiccups along the way, she added, “It took a little while, but we became allies. He was a dear friend and a wonderful human being. He was always interested in exploring any possibility for a play. Any ideas we had, he would say, ‘Try it.’ He was always interested in our contribution.” She went on to work with him in several productions in the post-Chelsea years.

In an email, Eleanor Reissa, who worked with Kalfin after the Chelsea years on several shows, including Yentl in Yiddish, wrote to say, “He treated each new project as though it was the first—which is what we all crave in the theatre. Even though he was around forever, he was an innocent, nearly wide-eyed in his love for the theatre. Certainly wide-hearted. I think of his joy in the work, his patience and care and love of the artists, always including younger ones whom he treated as peers.”

Bob welcomed input from everyone. The janitor? Why not. Students? Certainly. That’s how Yentl happened: It was Philip Himberg, who had done an internship at Chelsea when he was at Oberlin College, who read Yentl in a class and sent it to Kalfin, thinking it would make a good play. Kalfin agreed, commissioning Leah Napolin to write it, and the rest is history.

I myself entered the story as a grad student. I wanted to do my dissertation on Chelsea Theater, and asked Bob if I might look at the files. My knees were still shaking—I was in Robert Kalfin’s office!—when he said sure. And how would I like to come to rehearsals and interview everyone who’d worked there?

He invited me to watch him direct Frank Langella in the Kleist play. I was there from first rehearsal to last tech as two artists took enormous risks; no rehearsal was like any other.

Later, I asked him how he got Hal Prince to Brooklyn. “I asked,” he replied simply, as if it were perfectly natural. I’m not sure how I went from there to sitting in Prince’s office, picking his brain about Candide, or talking to the long list of luminaries and not-yet luminaries who were part of Chelsea’s history. But Bob made me feel confident, able to try anything.

Every so often, I’d ask him if he thought an approach I was considering was “right,” and he would advise me to “just try it.” Although a professor at NYU was officially my dissertation advisor, it was Bob who set me free. I had not planned a career in journalism, but here I was, talking to everyone, trying every approach to writing about them, keeping what worked, discarding what didn’t.

Bob, along with Burl Hash, came to my doctoral defense at NYU, and when the dissertation committee asked me for revisions to make it “less breezy,” the two men rose to my defense, arguing that Chelsea wasn’t a stuffy academic institution. It was a bold theatre, and a book about it should be too.

Marilyn Chris phoned me when we lost Bob. Honestly, I’m still processing. I want to call him as I write: What, of the many things I could say about him, who, of the many people who loved him…? But I know what he would say. So I’m just trying it.

“Such sad news!” Glenn Close wrote in an email. “What a fabulous era of New York theatre he represented.”

Indeed.

Davi Napoleon is author of Chelsea on the Edge: The Adventures of an American Theater.