When New York City’s Atlantic Theater Company gave Rajiv Joseph a slot for his new play Guards at the Taj, he told them he already had the actors who should be cast in the production. Arian Moayed and Omar Metwally had been developing the play with Joseph for years, and he only wanted to do it with them.

So there were no auditions, and the show’s director, Amy Morton, had no say in casting, which is very unusual.

But it seems to have worked out: Previews for the play’s world premiere at the Atlantic start May 20, and play will also have productions at La Jolla Playhouse, Woolly Mammoth in D.C. and the Geffen in Los Angeles. “Everyone knows who these two guys are, and everyone wants to have them in their plays anyway,” Joseph offers by way of explanation.

Maybe so. But the backstory of the actors’ involvement is instructive. It was Moayed whom Joseph had in mind from the start, having previously worked with him on Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo, a Pulitzer finalist. Moayed played that show’s tormented Iraqi translator, Musa, first at the Kirk Douglas Theatre in California in 2009, then at Center Theatre Group’s larger space, the Mark Taper Forum, and finally on Broadway in 2011, where he received a Tony nomination.

And it was Moayed who suggested Metwally as the second actor for the two-hander Guards at the Taj; the two actors had met in 2003 in Tony Kushner’s Homebody/Kabul at Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago, and have been friends ever since. (Coincidentally, Morton also appeared in that production.)

“I’ve always wanted to work with Omar—I’ve always admired his work,” the playwright avows. “When Arian first suggested him, not only was I so excited, but I was like, ‘These are the guys who are going to do this play, and it’s going to be perfect with them!’”

Joseph began writing the play, which is set in India in 1648 as the Taj Mahal is being completed, about two years ago, utilizing workshop possibilities at Lark Play Development Center. When he had the opportunity, he would come into sessions with new pages for the actors to read, often cold. After one reading of the “completed” play, Moayed and Metwally brought in such big ideas for additions to the script that Joseph went home and did a total overhaul.

“The notes that have come from them are never about ‘I want my character to say this’ or ‘Why can’t my character do this?’—they’re more about ‘The spirit of the play is this,’ or ‘It feels like there’s a larger moment here,’” Joseph says. Both actors appear in a lot of new work, so they’re used to collaborating with playwrights.

Moayed is also artistic director of the theatre company Waterwell, which devises shows together as a group. But this amount of dramaturgical collaboration on a single play is rare, as is the length of time the writer and actors have spent together in the trenches.

“It’s usually a matter of months that you get to work on something, so to have an opportunity to let things really stew is really special,” notes Metwally. “The other thing that’s really great is that it’s such a small cast—just the two of us—so our input can have more impact, in a way.”

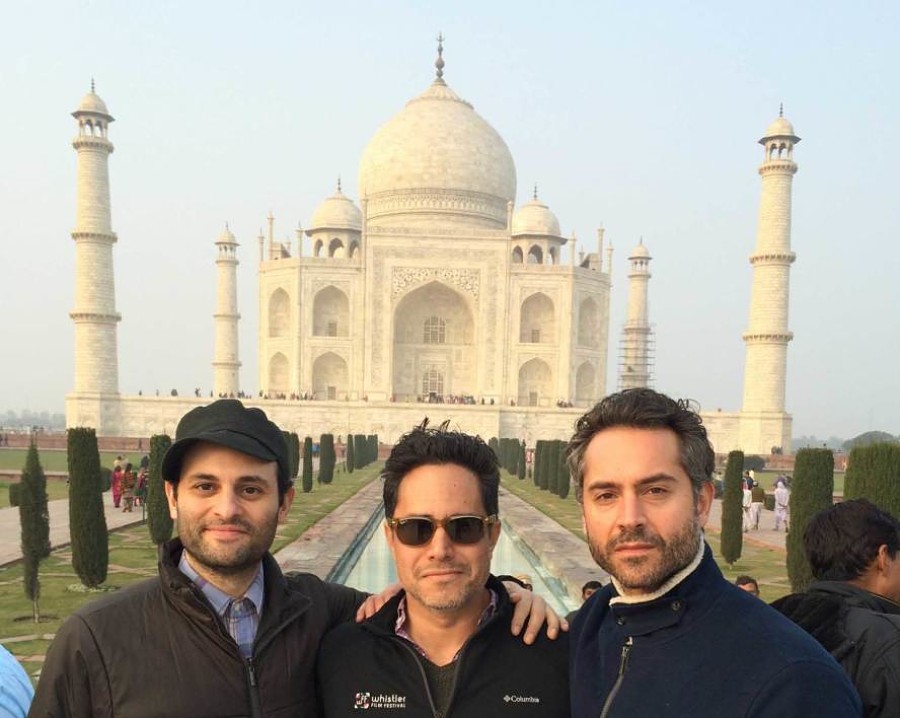

As if they hadn’t bonded enough already over these years of development, the three took a 10-day trip to India in late January to see their play’s title subject, the gleaming-white mausoleum built by the Mughal Empire in Agra. Joseph had visited the Taj Mahal before, but the two actors never had.

“So much of the emotional impact of the play revolves around them seeing it for the first time—I thought it would be really great if they did,” says Joseph with a grin. Angelina Fiordellisi, founding artistic director of Manhattan’s Cherry Lane Theatre, funded the travel through her organization, the Williams Family Foundation.

The visit proved immediately valuable. As Joseph recalls, “My favorite moment of the entire trip was when the three of us first stepped through the gates and just stared at the Taj for 10 minutes without really saying anything.”

As Guards at the Taj mixes legend with truth, the collaborators had been reading up on both the real histories of the period as well as the myths about it. Seeing the building in person added another layer.

“The way it triggers the imagination and makes this stuff real is invaluable,” Matwally testifies. “There’s this divide of centuries and culture, but suddenly we were there walking around in these places, and it became much more immediate and much more accessible for us.”

“Every inch of the place has the imprints of love and work and prestige and power and sweat,” adds Moayed. “Being there, touching it, feeling it—I can feel the texture of the walls on my hand now. What’s happened is that it’s now embedded in our DNA—you can’t get rid of it, it’s now there for life. That experience is going to impact the smallest of decisions, and it’s going to impact the biggest of decisions.”

An example: Joseph had been given a package of sketches of possible art for the play, and one of the ideas for the poster had an upside-down Taj Mahal with some blood dripping off it, showing that the world of the characters had been turned upside down (and that the famous monument exacted its toll on the workers who built it). “I liked the image, but we agreed that it feels totally wrong,” Joseph says. “It feels like defacement. I don’t want to do that. And I wouldn’t have thought so clearly about it if I hadn’t just been there. It may seem a tiny thing, but as Moayed points out, it’s also a monstrous one, as the image of the first production will be the image of the show for a while.”

While the three were in India, they also got some great news from afar. Unbeknownst to Joseph, the Atlantic had submitted the play for the Laurents/Hatcher Award, which provides $150,000 to an unproduced, full-length, socially relevant play by an emerging American playwright ($100,000 of which goes toward the play’s premiere production). Joseph had just read the whole play out loud to the actors as an exercise so they could hear it the way he heard it when a deluge of e-mails and tweets started pouring in about the award.

“Rajiv is a genius, but when Rajiv wins for a project that we’re working on, it feels like we’re all winning,” enthuses Moayed. “I was super-excited for the play.”

These shared experiences were also invaluable for a play that’s about a close friendship, in this case between two 17th-century guards named Humayun and Babur. When I met for an interview with the playwright and the two actors at a conference room at producer Jeffrey Seller’s offices (where Moayad’s Waterwell company has a space), it was the first time the trio had been in the same room since they returned from India a week prior, and they were catching up as if they hadn’t seen each other in months. They tease each other relentlessly, like brothers.

“We have very diverse backgrounds, and yet there’s a real commonality there, because we all have parents from places that are not America, and we all have traveled, so we share a perspective in a lot of ways,” reasons Metwally, who was born to an Egyptian father and a Dutch mother. Joseph’s father is from India and his mother is from Cleveland. Moayed’s parents are from Iran, where he lived until the age of five.

(Moayed remembers a line spoken by his character in Bengal Tiger: “You piece of shit man.” He and Joseph both especially cherished that line, because even though they are from different backgrounds, they knew from their own families that Musa, when angry, would skew his English precisely that way.)

After more than two years chewing over Guards at the Taj, the trio is ready for a production, but they’re glad they didn’t rush it. “When I was just starting out, I was just dying to get any play produced,” Joseph allows, “and now I have the luxury that some theatres would love to put a new play of mine up regardless of what it is. That’s happened to me a couple of times, and it hasn’t been good, so I have to be careful.”

At the time of the interview, rehearsals were about to start, and the three were anxious to get back into the play, and to add Morton’s input to the mix. “We want to change some ideas in people’s minds, and we want to have fun, and we want to do something special, and none of that happens in bubbles,” Moayed proposes. “It happens in an open environment. That’s where I think art can really thrive.”

Linda Buchwald is a writer based in New York City. Her writing has appeared in TDF Stages and Backstage.