The following is an excerpt from scenic designer Beowulf Boritt’s new book, Transforming Space Over Time: Set Design and Visual Storytelling With Broadway’s Legendary Directors.

Unless…to defend ourselves it be a sin

When violence assails us.

— Othello, Act 2, Scene 3

For 25 years, I thought that politics didn’t make good theatre.

I went to school at Vassar College with a lot of idealistic people who wanted to make a political or social point with plays. Sitting through one too many ill-conceived, political-axe-grinding productions taught me it wasn’t a good idea. Beyond school, I’ve found that explicitly political theatre easily gets preachy, and that preaching is frequently to the choir. Though I generally agree with the message, this doesn’t tend to make for good storytelling. I found myself firmly against the whole idea of political theatre until Kenny Leon showed me I was wrong.

In November 2018, Ruth Sternberg, the director of production at New York’s Public Theater, emailed to check my availability to design for Shakespeare in the Park the following summer. There were a few jobs on my wish list at the time, and designing at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park was high among them. The two shows the Public was planning for the summer of 2019 were Much Ado About Nothing and Coriolanus. It was their rule to hire a single set designer for both productions in the hope that some elements could overlap to save money and—more important—time, because of the quick turnaround between the shows.

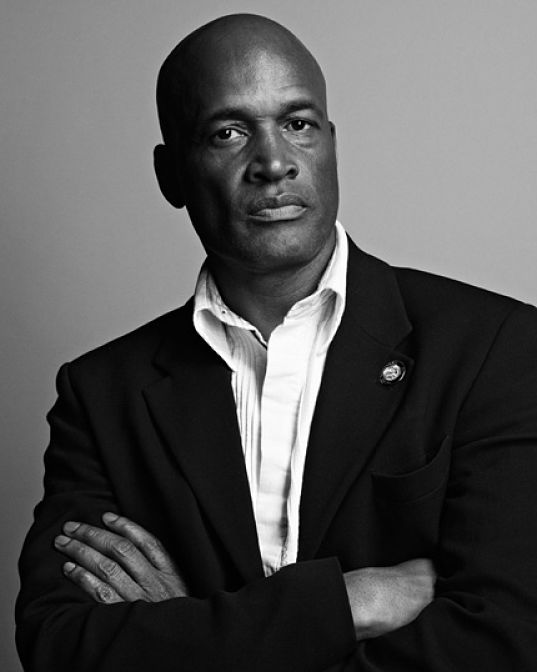

Kenny is a tall man with a gleaming shaved head. He is classically square-jawed, handsome like a 1950s superhero, if 1950s superheroes had ever been Black. Among his many diverse credits are the Broadway premieres of the final plays in August Wilson’s epic Century Cycle. I’d seen Kenny at the September opening of my production of Theresa Rebeck’s Bernhardt/Hamlet on Broadway. “Great work, man,” he’d said. “I’d love to get in a room with you again.” After Ruth’s query, I immediately emailed Kenny to say how much I’d love to do Much Ado with him. The theatre is a hyperbolic, glad-handing world where people are often complimentary to your face and don’t follow up. I didn’t know Kenny well enough to guess if his kind words had been heartfelt or simply polite. But as it turned out, in January of 2019, I was hired to design both shows.

Much Ado was scheduled to tech in May. After quickly rereading the play, I arranged a call with Kenny to start discussing the production. Kenny lives in Atlanta when he’s not working in New York or Los Angeles, so much of our design process would happen by phone and email. I would soon learn that Kenny can be a man of few words; his side of the correspondence often consisted of either “yes,” “no,” or “I don’t think so.” But he was always clear, and when something needed more explanation, he’d provide it or say he wanted some time to think it over.

In that initial call, he told me he was planning an all-Black production set in modern-day, middle-class Atlanta. In fact, he wanted to set it slightly in the future and to have a Stacey Abrams 2020 poster on the set. Abrams, a Democrat, had recently lost a nationally covered governor’s race in Georgia, where serious voter-suppression issues had contributed to her Republican opponent’s victory. Kenny knew Abrams personally, and there was talk that she might run for Senate or even president in 2020. (She didn’t, as it turned out, though she would go on to create massive political waves in 2020 nonetheless.) He thought the poster would be a succinct way to establish time and place while offering a nod to current politics.

So they’re American military?” I asked. “Coming back from Iraq or Afghanistan?”

“No,” he said. “I’m talking about the war that’s going on in America right now.”

I paused for what felt like five minutes to digest what he’d said.

I love designing Shakespeare plays, but I hate the trend of picking a “period” to place them in. The plays are great enough to survive it, but I’ve gotten a bit tired of seeing them set in random historical contexts for no particular reason. That said, I love setting them “now.” The Elizabethan language can be jarring at first, but audiences are so attuned to the nuances of the clothes, surroundings, and behavior of our own time that I think it deepens the storytelling. Most of the plays work brilliantly in the present and can easily withstand the occasional anachronistic sword or dagger. I was very happy that Kenny had decided to place the play in contemporary America.

He tossed out a few other images. He wanted to include a place for a live DJ on the set. He wanted an American flag and an old car up on blocks. “Most of the play is a comedy,” he pointed out. “It’s about love and deception and marriage. It deals with people—in this case, Black people—going about their everyday lives. But of course at the beginning, they’re coming back from the war.”

“So they’re American military?” I asked. “Coming back from Iraq or Afghanistan?”

“No,” he said. “I’m talking about the war that’s going on in America right now.”

I paused for what felt like five minutes to digest what he’d said. I’m a middle-class, middle-aged white guy working in a fairly liberal industry, living in a fairly liberal city. I try to be “woke.” I’ve gone to more protest marches, mailed more letters to representatives, and written more postcards to likely voters than I can count. But my personal experience is massively different from that of a Black man, and I knew it. This was 18 months before the murder of George Floyd and the international explosion of the Black Lives Matter movement, but I was aware of the awful statistics: the massive numbers of Black people incarcerated and killed. I would have described those as terrible civil rights violations, but Kenny had used the word “war,” and that had set my mind reeling. It reframed my perspective in an instant. If I were a Black man, I thought, watching my people being imprisoned and killed, facing the reality that it might well happen to me, how could I describe it as anything but a war?

In that moment that felt like an eternity, I was grasping an idea that was new to me. A window cracked open, and I saw a slice of the world through new eyes. Could we build a production that would open that window for others? It’s what art is always supposed to do but seldom does.

I think I just said, “OK, got it.” We chatted a bit more. I told Kenny I’d send him some ideas soon.

Beowulf Boritt (he/him) is a New York-based scenic designer.