You’ve probably never heard of Chug, arguably the least celebrated among the hundreds of works on offer over the decades at the annual Humana Festival of New American Plays. Believe me, there’s no shortage of competition. Nevertheless, of Ken Jenkins’s jaunty tour through a Southern Indiana backwater, I won’t ever forget the big reveal: a restaurant-grade freezer filled to the flippers with frog legs, individually bagged and solid as the tilapia at Trader Joe’s. We were invited, back then in 1981, to take the bounty off his hands for a song, should we entertain a hankering for such victuals.

Plenty of other, more famous works were birthed, mewling or howling for affection, at the Louisville festival. For more than three decades, it was a vernal rite as attention-demanding as the Run for the Roses a few weeks later. For some of us, at any rate.

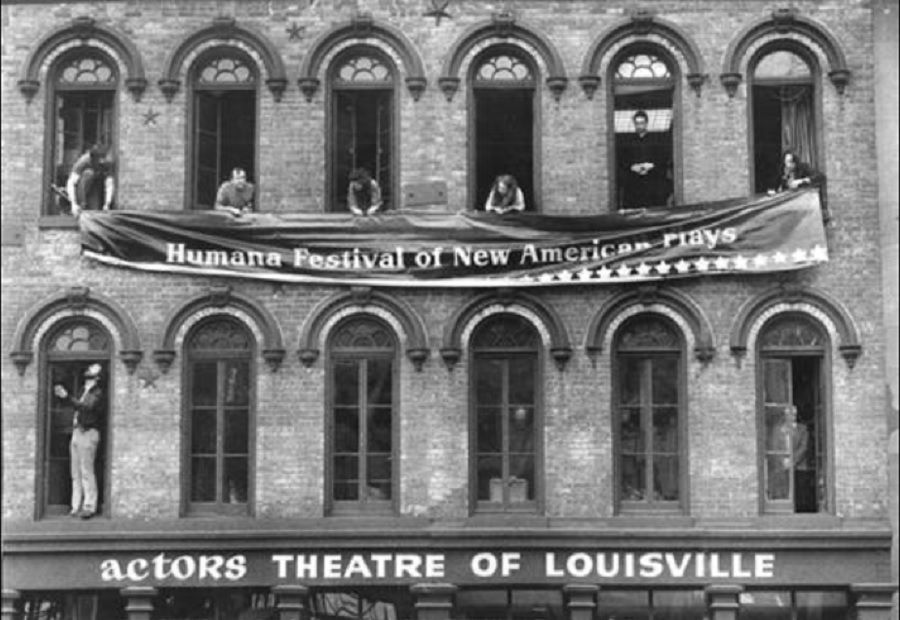

Speaking of rates: In the late 1970s, lacking a home base but adept at pitching stories for a pittance to penny-pinching editors, I scored assignments from five big-city broadsheets, assuring the festival (and my byline) of exposure to a significant chunk of the American populace for compensation which, in the aggregate, almost covered the cost of flying to Kentucky, bunking down at the posh-like Seelbach Hotel among fellow ink-stained kvetches (remember ink?), producers, agents, managers, spouses, not-spouses, and all manner of hangers-on, and taking in a long—a very long—weekend of shows at the multi-stage complex comprising the Actors Theatre of Louisville.

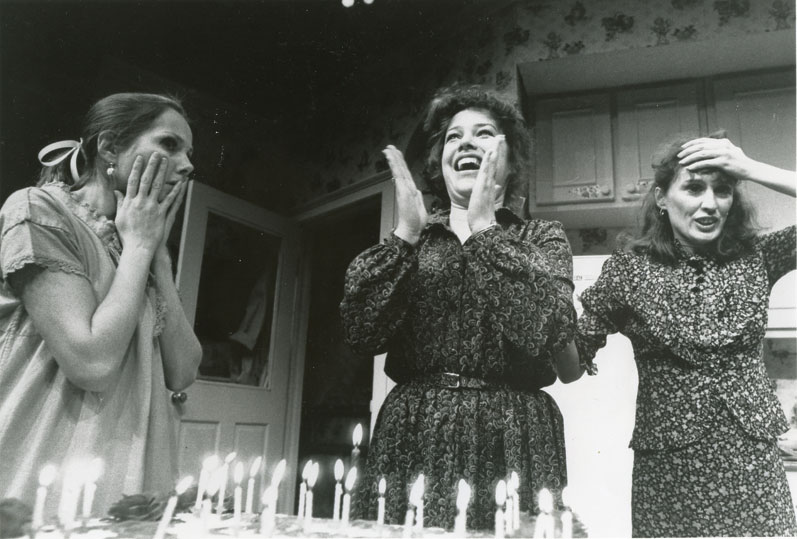

For every Chug (which I loved, by the way, but I also loved Ishtar) there were, reliably, a handful of gems and noteworthy debuts that unstuck our eyeballs and unclogged our ears despite taking in three, or five, shows a day. The festival made its debut in 1976 in the deft and sculpting hands of producing director Jon Jory (whose father, the legendary film actor Victor Jory, gazed down from his portrait over the entrance to the theatre’s smaller house, named in his honor). Indeed, the same program in which Jenkins had appeared in his own play also featured Mary Gallagher’s Chocolate Cake, the edible object of desire for two peckish, deeply unalike women—indelibly played by pre-stardom Kathy Bates, and Susan Kingsley, an actress whose early death still is mourned in certain quarters—thrown together at a salvation seminar for sweets freaks.

The ritual sacrifice of cake had also figured in the big hit from the previous year’s festival, the world premiere of Beth Henley’s Crimes of the Heart, a Southern gothic comedy (sex, firearms, photographs) that later would be celebrated with a Pulitzer Prize and a long Broadway run. And Crimes wasn’t even the festival’s first Pulitzer winner, a distinction that belonged to freshman playwright Donald Coburn’s poignant gerontological two-hander, The Gin Game, which also played well, and long, on Broadway.

With Jory at the helm and the suave executive director Alexander Speer steadying the ship while schmoozing the high-rollers, Actors Theater would begin unveiling shows each fall in preparation for the spring extravaganza. The Festival of New American Plays (both the name and the configuration would evolve over the years) launched a number of luminous careers, especially for such women playwrights as Henley, Marsha Norman, Wendy Kesselman, Lynn Nottage, Kathleen Tolan, Theresa Rebeck, Susan Miller, and the pseudonymous Jane Martin, along with such male newcomers as Lucas Hnath, Will Eno, and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. At the same time, it affirmed many theatre standard bearers, among them Horton Foote, John Guare, Tony Kushner, Arthur Kopit, and Donald Margulies (whose Dinner With Friends was another Pulitzer winner). The late Paul Owen, ATL’s game resident designer for nearly four decades, had a preternatural gift for creating eye-catching sets that could be loaded and struck in the blink of an eye, making the weekend’s quick-change, speed-freak derby possible.

Generous and game ATL board members housed visitors and hosted dinners for the transient, while an after-hours cabaret offered gossip and lubrication for those of us not on deadline (and some who were, but I’m not talking) and a showcase for the abundant young talent.

Now, after two pandemic-ruined seasons (one dark, one featuring a slate of new works in virtual form), the Actors Theatre of Louisville has essentially declared the festival as we knew it dead. There are so many reasons to mourn its passing, but I will dedicate my Kaddish to this: We critics tend to be solo fliers, rushing home when the curtain falls to spend time in another darkness, sorting out our responses to the work under review. We are, in many ways, the opposite of theatre artists, who must work in collaboration to find success. We rarely play well with others.

But the Festival of New American Plays was an exception, demanding collegiality and compelling us to acknowledge, at least once a year, that we also are part of a community dedicated to discovery and its mirror, renewal. Such is the stuff of spring. When there was a marathon, we were pleased—honored, even, and communally exhausted—to grab the baton and pass it along. That’s worth celebrating, and missing.

Jeremy Gerard (he/him) is a critic, occasional contributor to American Theatre, and the author of Wynn Place Show: A Biased History of the Rollicking Life & Extreme Times of Wynn Handman and the American Place Theatre (Smith & Kraus, pub.)