The theatre provocateur Richard Schechner has been among the most influential, innovative, and scholarly makers and thinkers in the world of theatre for more than 60 years. He has been at that forefront since the mid-1960s, when he helped found or lead several organizations: East End Players, Free Southern Theater, the New Orleans Group, and, perhaps most memorably, the Performance Group, which he led from 1967 to 1980, and East Coast Artists, which he was part of from 1992 to 2009.

In addition to directing plays all over the world, he was a professor at Tulane and at New York University, where he was one of the founders of NYU’s Performance Studies department in the Tisch School of the Arts. He has been the editor of TDR (The Drama Review) for several decades, and his numerous books include Public Domain: Essays on the Theater (1969), Environmental Theater (1973), Theatres, Spaces, and Environments (with Jerry Rojo and Brooks McNamara, 1975), Essays on Performance Theory: 1970-1976 (1977), The End of Humanism: Writings on Performance (1982), Performative Circumstances: From the Avant Garde to the Ramlila (1983), Between Theater and Anthropology (1985), Performance Theory (revised, 2004), Performance Studies: An Introduction (third edition, 2013), Performed Imaginaries (2014), The Future of Ritual (1993), and Over, Under, and Around: Essays on Performance and Culture (2004). Edited works include Dionysus in ‘69 (1970), Ritual, Play, and Performance (with Mady Schuman, 1976), By Means of Performance (with Willa Appel, 1990), and The Grotowski Sourcebook (with Lisa Wolford, 1997).

A list of some of his awards gives an idea of his eclectic and wide-ranging interests: the Thalia Award from the International Association of Theatre Critics (IATC), the Lifetime Achievement Award from Performance Studies international (PSi), the Career Achievement Award for Academic Theatre from the Association for Theatre in Higher Education (ATHE), and an American Academy of Religion, Eastern Region Award, for Inspiring Scholarship.

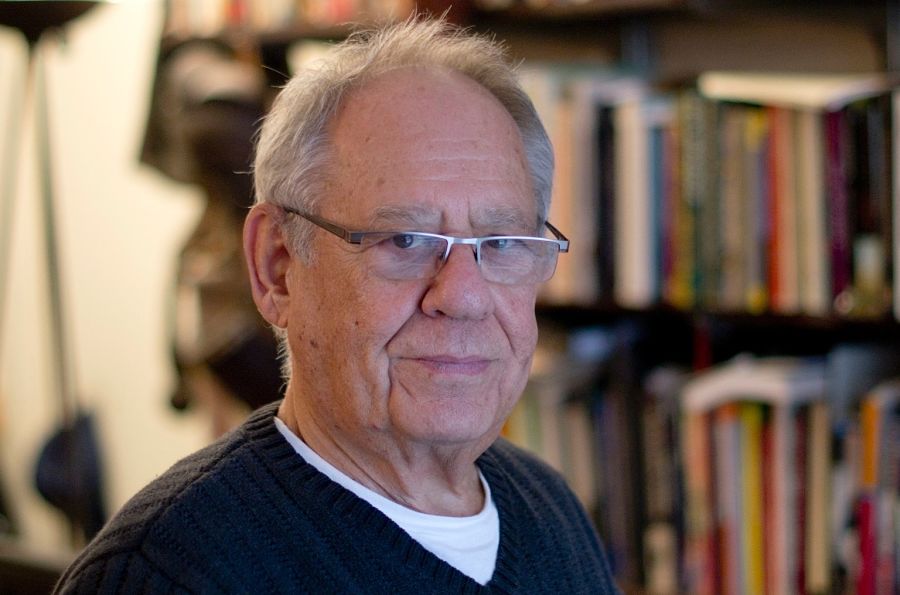

There is no doubt that he has earned esteem in the world of theatre as well as in academia. When I sat down with him last year, I wanted to know: Who was Richard Schechner before he rose to prominence in the theatre? He’s been widely influential in his field, but what were some of the formative influences on him? I came away impressed.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: In 1957, you were with the students in Little Rock before they were escorted by soldiers past Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus and into Little Rock High School. Could you tell us what you witnessed and what it was like to be there that day?

RICHARD SCHECHNER: As best I recall, I was the only white person in the room. To set the scene: The youngsters were 14, 15 years old—they were high school students. I don’t remember exactly how many there were. I do remember that we were in a room that was in a kind of basement. We used to have houses like this in Newark where I lived until I was nearly 14, where you were below the street level and you looked up and you saw a row of windows at about your eye level; the light came into the basement, but you were still below street level. The windows were only about two-and-a-half feet high and about four feet across. There was a row of them. The kids were down there, and we could all look out through those windows at the street and at the high school. There were steps going up and there was a huge crowd out there. They were shouting terrible things, the N-word, and so on.

Looking back at it now, 60 years later, I can see how this was a performance in a certain way. They were rehearsed. They were dressed to a T. They were dressed to go to church, not really to go to high school. Everybody knew what was going to go on, except for the children, maybe. They knew what they were supposed to do, but did they know that they were part of a great historical event? They were told—I remember, the adults said, “Keep calm, just walk out the door, cross the street, go up the steps, and go to the school. Soldiers are there; the governor is there; people are shouting.” They said, “Don’t worry.” It was like a script. They said, “It is all arranged. Don’t worry. When the time comes, the governor will step out of the way and you will go into the school.”

Again, in hindsight, I realize it was all arranged. Gov. Faubus had to take this stand from his political point of view. Eisenhower had nationalized the state guard, and they were to say, “Governor, step out of the way.” And he was going to step out of the way; he was not going to go to jail, and there was not going to be a huge riot there. It was extremely exciting, especially for me, because I had been studying and writing about Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. the Board of Education. I had done a lot of research about that. I knew the history behind it and the momentous occasion it signified. I don’t remember now if that was the first integration of anything; I think there were other schools that had been integrated before. But it was certainly a massive one.

At a certain point, I imagine around 8 in the morning, the students were told to go. They walked up the steps and the crowd went crazy. This was the decisive moment, because no adult was going to accompany them. They were going to school; it was not the grown-ups who were going to school. The guard came and somebody escorted the Governor off. It could be seen that he did not leave of his own free will. They were in the school and the doors closed. Event over. I don’t remember what happened afterward.

When you were a student at Cornell, you met and wrote about Thurgood Marshall. You said that he changed your life. Could you talk about your interaction with Marshall?

Let me back up a bit. I was born and brought up in Newark, N.J., before Newark was an all-Black city. In the neighborhood I lived in, we were basically in a Jewish ghetto. Except for one friend, all of my friends were Jews, everybody around me. Philip Roth wrote about it, the Weequahic section, right next to a Black section. The synagogue I went to—which my great grandfather founded—was in a largely Black community, because the Jewish community had moved and the Black community had expanded. The huge white flight to the suburbs had not occurred yet; this movement was within Newark. The schools were segregated to some degree because the neighborhoods were largely segregated, but there were some Black kids and white kids together. There was also a large Italian community, which was in the First Ward and in Ironbound, which became Hispanic and Portuguese. There were other communities too, Irish, German. Newark was a very neighborhoody city. I grew up, more or less, within the insulation of my own community. When we went down to Weequahic Park, we’d interact with other kids when we were doing sports, but I only had one close friend who was not like me.

I knew from early on that something was wrong within the society—that things were wrong. My father worked for his father; his father was an insurance guy who also did real estate. He must have owned or was an agent for housing in the Black ghetto, which was not called “ghetto” at that point. Anyway, on Saturday afternoons, my father, my mother, and I—I was one of four brothers, but somehow I was in the car—would go when he was collecting those rents, or whatever he was collecting, and I saw people who were living much worse than we were living in terms of their physical housing. And I remember one time, some kids came and rocked the car. There was no love lost for what they thought of Jewish landlords and Jewish agents coming to the Black community to collect money. I was seven or eight years old, and I realized that something was wrong. It was not until years later that I worked it through, after my bar mitzvah at age 13, when my family moved to the suburbs, South Orange, and I went to Columbia High School and then to Cornell. I had a sense that my parents and my mother’s father, especially, had a keen sense of social justice. Not that they were great activists; I don’t really know what they did, but they did know right from wrong and that the way things were was wrong. That much I am sure of, because at the age of 18, I would not have had those views unless they were somehow inculcated in me.

At any rate, when I learned the case was handed down in 1954—it must have been argued in 1952 or ’53—I was a freshman or sophomore. I was working all the time on the student newspaper, The Cornell Daily Sun. I said I wanted to write about those things. I found out that the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, was the organization bringing these cases, and I found out who the chief counselor was. It was Thurgood Marshall. I wrote him a letter. I got an answer: “Dear Richard (maybe he said Mr. Schechner, I don’t remember), if you want to learn more about it, you have got to come and see me. My office is,” and he gave me his address on 125th Street. I did not even know New York, no less Harlem. As a boy, I went to New York with my family once or twice a year, usually to Radio City Music Hall for the holiday show, and sometimes maybe to the theatre.

I remember going up to 125th Street. The best I recall is the NAACP offices were on the second floor, not on the ground floor, but Marshall’s office was on the ground floor. I remember meeting him. He was a big man. He was tall. He had a mustache. He was tan, not super dark. He was a famous lawyer, and he threw his feet up on the desk. I will never forget that. He said, “Sit down, Richard, and I will tell you something.” He had a kind of drawl—he did not speak New York English. He gave me a beautiful lecture, for a few hours, on the whole history of Plessy v. Ferguson, segregation—the idea of separate but equal being unequal. I believe he had already presented the case to the Supreme Court. He changed my life, because here I was facing a man who was a great man; I didn’t know that at that point. I was very impressed with him: obviously, he became a Supreme Court justice–a great thinker. But also, he was informal; he was not stuffy; his feet were up on the desk; he was leaning back; he was talking; he was probably mixing legal ideas with stories and so on, and he explained it to me. That he gave me the time, the generosity, was extraordinary. Later on, the year after I graduated, when I wanted to go and write about the confrontation with Faubus in Little Rock, it was Marshall who gave me the letter to Daisy Bates, the head of the Arkansas NAACP. He wrote to her about me. He must’ve said nice things, because she replied, “Come on down.”

Marshall engaged my sense of social justice, my sense of racism and racial inequality, and my sense that society must change and obey the rule of law. I think that is very important. Marshall was not a guy who would say, “Break a few windows, riot, and things will change.” He understood people’s pain, but he also had a deep, deep respect for the law, which moves in its own way. He was, after all, a lawyer, and he became a Supreme Court justice. That was not an act he was putting on, that was who he was. So there were several things that formed my life, but meeting Thurgood Marshall was a very, very important part of it.

In 1964, Freedom Summer, three Civil Rights workers were murdered in Mississippi: James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. By then you were working with Free Southern Theater in that state. How did you find your way to that theatre, and how did those deaths impact what you were doing?

Well, every time you ask me a question, there is always a backstory, and this is a complicated backstory. Some of the things that changed my life were serendipitous. I graduated from Cornell in 1956, with honors in English; I was a very good student. Then I went to graduate school at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. I didn’t like it. That was the academic year 1956-57. In 1957-58, I went to Iowa, where I was in Paul Engle’s Writers Workshop. I wrote a play as my master’s thesis. In the summer of 1957, I started a theatre in Provincetown, the East End Players, and I continued it during the summer of 1958. By then I knew I wanted to be a college professor and I wanted to do theatre. I knew that I had to go on and get a Ph.D.

I also knew I had lived a very insulated life: My life experiences were Ivy League college, summer theatre in Provincetown, that kind of thing. I said, how am I ever really going to meet people who are really not like me? This has been a big theme in my life. I like to meet people who are not like me, as well as some people who are like me. I don’t consider social comfort to be a particularly positive value in education. I think discomfort, particularly with avant-garde stuff, and socially/culturally unfamiliar stuff, where you’re uncomfortable, not quite at home, you can learn a lot from that. You have to adjust; you have to change. It is easy to sail a boat on a calm sea. But you really know what it’s about when the wind comes up and you are a little too far off shore.

To make a long story short—I went down to the draft board and said, “Draft me.” It was called “volunteering for the draft.” The difference between volunteering for the draft and enlisting was that when you enlisted, you had to serve for three years. The draft was only two years. I wanted to meet people not like me, but two years in the army was enough for me. Volunteering for the draft meant that the draft board—they still had a universal draft—could meet their quota. If some dumb kid came in and said take me first, that made their lives much easier.

There are a lot of stories about me and the army. By that time, 1958, I was 24. Why didn’t I take a commission? I had a master’s degree; they said, “Become a lieutenant. Join the reserve and serve only six months and become an officer.” I said, “No, I want to be an enlisted man.” I wanted to experience what the ordinary person did. They took me, but they were always a little suspicious of me. Over the years, the government built a big file on me—I’ve used the Freedom of Information Act to see it. In the army I was a few weeks at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Then I was sent to Fort Polk, La., for basic training and assignment. The soldiers joked about Fort Polk, which is in Leesville: “If God wanted to give the world an enema, Leesville is where he would insert the tube.” But even if it was the asshole of the world, a terrible place, it had its own charm. I remember at one of the bars there was a one-armed B-girl, a dancer who was fun to be with. At Polk, I was a lifeguard at the officers’ pool.

Then one day, I got a phone call from a schoolmate of mine from Cornell, Tim Shelton, who lived in New Orleans. He’d been north and called my family in New Jersey. They told him I was down in Louisiana. Tim told me to get a three-day pass and come to New Orleans. Tim got me a blind date with Caroline W., whose father, Daniel, was the head of the Spanish and Portuguese Department at Tulane University. I knew nothing about Tulane except that it had a football team called the Green Wave. Anyway, Caroline and I became very, very close. I would get to New Orleans whenever I could. New Orleans was a city the likes of which I’d never seen before. It was, especially down in the Quarter and back in Basin Street, near the river, culturally integrated. Multicultural like I had never experienced before, its own particular culture. Aside from New York, it is the place in the United States I like best. I got very much involved in New Orleans.

To cut to the chase, because there are so many stories within the story, when I got out of the army in 1960, I decided to get my Ph.D. at Tulane. After finishing coursework and passing my qualifying exams, I did research in France in the academic year 1961-62. I wrote my dissertation on Eugene Ionesco. Tulane hired me as an assistant professor and as the editor of The Tulane Drama Review, TDR.

Now, getting back to Freedom Summer—I didn’t forget it. My younger brother William was a newspaper reporter and once was the general manager of WBAI here in New York. Then he went to San Francisco and became a TV newscaster and anchor. He went to college at Oberlin, where his roommate was Gilbert Moses. In 1963, Gil, John O’Neal, and Doris Derby came to Tulane looking for my brother who they thought was the guy teaching theatre. When they got there, they realized of course that I wasn’t Bill. I said, “No, I’m Richard, and I am very interested in your project.” They were happy because they were looking for a partner for expanding their Tougaloo Theatre workshop into what became the Free Southern Theater. By then, I had had the experience with Thurgood Marshall and already was involved in what we called the Civil Rights Movement. I had taken part in some demonstrations and was arrested at a sit-in at a lunch counter in the Maison Blanche department store in New Orleans. I was very interested in their theatre project, but I said, “I’m teaching here, I can’t go to Mississippi for months at a time.” We had an intense meeting over several days—and the outcome was that I became one of FST’s three producing directors, along with Gil and John, and the FST headquarters moved to New Orleans. We would still work in rural Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama—mainly in Mississippi—but we moved from Tougaloo College to New Orleans. The whole story is in a book I co-edited with Gil Moses and Tom Dent, The Free Southern by The Free Southern Theater (1969). That is how it began, with a mistaken identity to some degree.

At first, during Freedom Summer, the FST was a Black-and-white theatre. We went to New York and auditioned for participants. That’s how Murray Levy and Jamie Cromwell joined the FST. There were others, too—together we formed a whole repertory company. (See the book for details.) During Freedom Summer we performed Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, Ossie Davis’s Purlie Victorious, and Martin Duberman’s In White America. I directed Purlie.

Now, you were asking about the murders of the three young people. I don’t know how to put this. It was a shock but not a surprise. It didn’t affect what we were already doing, because we were already going to perform in those places. It galvanized us. It was horrible and outrageous, but it was not unexpected. Shocked, because who wants young people murdered; not surprised, because the whites, the racists in Mississippi, they were really bad people. We got shot at a few times. During that summer, we would be driving in our truck and a car would come by the side of us. “Nigger, get out of here!” or “White trash, get out of here!” or “We’re going to get you.” They were not joking, so what happened with the murders is that the horror we feared happened.

The other side of it was the people we met, the people we performed for. Incredible Black audiences, in farmyards and churches. Two of the three plays we performed we knew would probably be successful. In White America would be something that everybody would respond to—a documentary relating some of the history of racism in America. Purlie Victorious is so hilarious. It sends Jim Crow way up—it is a very, very funny piece. Gilbert insisted on Waiting for Godot. I admired Gil’s idea, but thought people wouldn’t go for French existential abstraction, a play with no plot performed on a nearly bare stage. What would it mean to these people in the rural Deep South? I was wrong. They got it. It was very, very successful.

1964 was an extraordinary summer, in terms of meeting people and doing workshops and performing in churches and backyards. The sense of commitment—a time when your life was on the line. You were either on this side of the line or that side of the line. You could not be neutral in those circumstances. Brecht once said, “To be neutral is to support the stronger side.”

When John O’Neal and Gilbert Moses decided that Black folks should control their own theatre, you were pushed out. Could you share with us more about what happened at that time and why this came about?

That meshes right in with Malcolm X, the Panthers, and Elijah Muhammad. Black Power versus white privilege. I think it was probably 1965 when the Blacks in FST said that they wanted it to be an all-Black theatre. I understood, and would never write anything against it. But all the same, I felt that I built this theatre, too. I believe these racial categories are more complex than we sometimes make them. I never considered myself totally white. I am Jewish, however complex that is. When you go to the Nazi rallies in Charlottesville: They are shouting, “Death to niggers! Death to kikes!” Jews are not welcome by the far right. A few times in my life I have experienced antisemitism directly. At the same time, I was sympathetic to the FST becoming an all-Black theatre—even if I also thought, “Why me? I know I’m white, but I’m not quite white.” There’s plenty of historical evidence to say that lots of white people would look at Richard Schechner and say he is not white. Is race—which is socially constructed—a question of skin color? Isn’t it culture mostly? Think of Walter White, founder of the NAACP, who said, “I am a Negro. My skin is white, my eyes are blue, my hair is blond.” Anyway, I accepted the FST becoming all Black, while Murray Levy, who is also Jewish, didn’t accept it. He said, “I’m really Black,” and they let him stay. He was so innocent in his own way, so totally devoted.

I was asked to remain on the board of directors. It was paradoxical: As a producing director, I was directing and leading workshops. As a board member, I was relegated to helping raise money. That was so much a stereotypical “let the Jew raise the money.” It seemed to me to be nuts at that point, because it reinscribed a power structure that I had worked to overcome and had never really wanted to subscribe to. I don’t mind raising money if I could do it, but I didn’t want to just do that. I served on the board for one year. By then I had begun to do more of my own theatre work. But Gilbert, John, and I remained friends until each passed away, Gil in 1995, John in 2019.

You directed Ossie Davis’s Purlie Victorious. What was that experience like, and what dealings did you have with Ossie Davis?

I don’t think we dealt with Davis directly. I don’t remember speaking to him or communicating with him in any way. He gave us permission to do the play, but I didn’t meet Ossie or his wife, Ruby Dee. They may have come to see the show or may not have, I can’t remember. Purlie is such a send-up, set on a plantation. The audiences were so happy watching it. In White America reminded them of things that are true and painful; Waiting for Godot was existential, both deep and humorous in places. But Purlie made fun of the Man right there in the middle of Mississippi. That was really liberating, because it was making fun of the world we all hated, turning that world upside down. And doing Purlie right there in rural Mississippi and Louisiana, in circumstances so different from Broadway—remember, nobody paid for a ticket to the FST. It was a theatre for those who had no theatre; a lot of people had not ever seen theatre.

Can you tell us about any contact you had with the playwright Ed Bullins?

Bullins knew who I was when he wrote me. He was reading TDR and he wrote me a letter that said, in essence, “You’re a white guy. How can you understand Black theatre? You would never let me into your journal.” I met him. I remember he was like a wrestler in a certain way, not tall but very muscular. I said, “Okay, Ed, an issue of TDR is yours. Put whatever you want into it; you have a complete issue. All I want to do is to write an introductory editorial explaining that I said that.” He was really surprised, shocked. He said, “You don’t want to read it?” I said, “Of course I want to read it, but I have no censorship. I want to read what you put in the journal, but I will not have an inch of censorship. You put whatever you want in.” So we got on; he was really surprised by that. And I am proud of what Bullins brought; it’s a very good issue: vol. 12, no. 4, Summer 1968. The summer after the murder of MLK. That issue included plays and essays by Bullins, Larry Neal, LeRoi Jones (before he became Amiri Baraka), John O’Neal, Woodie King Jr., and many more. The issue really opened up a kind of theatre that was not so known to the non-Black world, and maybe even to many in the Black world. A theatre that did not aspire to Broadway. It was its own thing.

You directed August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom in South Africa in 1992. How did that happen, and what was that experience like?

In New York in the late 1980s, I think, I met Mavis Taylor, a white woman who headed the Drama Department at the University of Cape Town. She did a lot of work in the townships. Mavis invited me to come to South Africa. It was my first trip to sub-Saharan Africa. In South Africa I did some workshops in Capetown and Johannesburg. In J’burg I met Carol Steinberg, a theatre director and playwright, who participated in one of my workshops. Carol’s husband was the head of a trade union and was very active politically. Both Carol and her husband worked to end apartheid. Racists targeted them—they had to sleep underneath their bed on many nights because people were shooting through the windows of their home. Carol asked me to come back and direct a play. I wanted to do that. I wanted to direct an African American play. Of course, I thought of August Wilson. I particularly liked Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom because it integrated music into the text. It wasn’t a musical in the American sense; in fact, in the original Broadway production, there was no live music. It is a play about Ma Rainey, a great singer, “Mother of the Blues,” her band, and a day in a recording studio in Chicago in 1927.

I was invited to direct the play for the Grahamstown National Arts Festival, the major event of its kind in the country. Grahamstown is the site of the Settlers National Monument, commemorating the British colonizers. Of course, such a monument reverberates in several directions—recalling the epoch of white supremacy as well as, more recently, the liberation from apartheid. In 1994, two years after my production of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Nelson Mandela rededicated Grahamstown and the festival as a bulwark of inclusion. In 2018, Grahamstown was renamed Makhanda.

By 1992, the year of my production, several anti-apartheid artists had performed at the Festival—but audiences remained overwhelmingly white. I agreed to direct for the Festival only if Ma Rainey would play to integrated audiences. Ma Rainey has an integrated cast: Ma, her nephew Sylvester, Dussie Mae, and the band are Black, while Ma’s manager and the recording studio personnel are white. That was no problem for the festival organizers. But what about the spectators, I asked. The organizers said that ticket sales would be open to anyone. However, I knew that the prices would be such that ordinary Blacks living in the township could not afford to attend, even though the venue was a gymnasium in the township. In order to get a local Black audience, I told the Festival organizers that the environmental theatre style of the performance—three separate scenic areas with spectators in between—necessitated full-scale dress rehearsals with live audiences. We agreed on three previews with no admissions charge. The audience for these previews was overwhelmingly Black and “colored” (an apartheid racial category).

I made no changes in Wilson’s script, but added live musicians. I believe that on Broadway they used canned music. Carol Steinberg, the assistant director and dramaturg for the production, suggested Sophie Thoko Mgcina, a well-known singer, actor, and musical director. Sophie’s powerful voice, strong stage presence, and inspiring acting fit Wilson’s portrait of Ma Rainey perfectly. We opened the second act with a set of Rainey’s songs drawn from her albums. These were presented as rehearsals for the upcoming recording session which is a focus of the play. Experiencing Ma Rainey’s songs sung by a live performer accompanied by an accomplished band brought the reality of the drama to life. After Sophie/Rainey sang three songs, we reverted to Wilson’s script, where Sylvester is unable to say his lines without stuttering. I don’t know if Wilson ever found out, but it didn’t disturb his play. In my opinion, it strengthened it.

Another thing: The African artists I worked with, and the African audiences we performed for, knew very little about African American history or experience. They knew what happened in South Africa and they were participating in the struggle to end apartheid and bring in majority-rule democracy, in effect a Black government, but they didn’t know details about the then-current circumstances in the USA, and even less about the situation in the 1920s. I found myself in the ironic and paradoxical position of teaching Black Africans about the African American experience. First, I shared what I knew and what I could gather with the cast. This material formed the basis for an extensive lobby display of books, newspaper clippings, photographs, and documents. I wanted the cast and the spectators to know what it meant to be Black in America, both in Ma Rainey’s time and in our own, that is, from her day to the 1990s. I strongly felt that this information was necessary to understanding Wilson’s play. The South Africans knew Black American music—blues, jazz, the rap of the 1990s—but they did not know the experience of Black Americans. Without somehow giving audiences information about that experience, they would hear the words of the play without grasping the lived reality driving those words. The lobby exhibition really opened people’s eyes. The exhibition made a point that segregation and apartheid were similar.

Before I accepted the offer to direct in a South Africa in the midst of apartheid which was ending but not fully over, I said I wouldn’t go unless the ANC (African National Congress) gave its OK. They did. Then I contacted Wilson, whom I’d never met. I told him who I was, and I probably said that I was one of the originators of the Free Southern Theater, and that I wanted to do his play in South Africa. He gave me permission. That was it.

The production was successful, it really was an important cultural event. The Grahamstown Festival was part of breaking apartheid, of pointing toward a new South Africa.

I know that before he died, August Wilson advocated strongly for Black directors to direct his work.

Well, he never gave me any problems. After the production, I think we sent him clips and a description of what happened. I hope he was happy about it: I think it was the first African American play produced in South Africa. What other white guys have directed his plays?

Bartlett Sher for Lincoln Center in 2009.

So I was the first non-African American to direct one of Wilson’s plays.

Yes, to my knowledge.

Nathaniel G. Nesmith (he/him) holds an MFA in playwriting and a Ph.D. in theatre from Columbia University.