Actor Glenn Kubota doesn’t celebrate his birthday anymore. Kubota is in his 70s but says he doesn’t “want to be reminded” about his age. “I celebrate enough of them,” he told me with a chuckle. “If you keep celebrating, it gets put in your mind that, ‘Oh, you’re a certain age.’ I don’t try to let the fact that I’m a certain age hold me back from doing what I think I can still do.”

Right now what Kubota can do is perform a 30-minute monologue every night as part of Out of Time, a new production from the National Asian American Theatre Company, presented Off-Broadway at the Public Theater through March 13.

A septuagenarian actor performing a long monologue might not be something to write home about, but for this fact: Out of Time is a collection of five monologues, each around 30 minutes long, all performed by actors over the age of 60. The entire show clocks in at an impressive two hours and 45 minutes, with one intermission.

In today’s youth-obsessed culture, where the meatiest acting roles are typically reserved for younger people, having a play entirely filled with older actors delivering demanding texts is notable. Kubota, who has over 40 years of acting experience under his belt, noticed that as he got older, the roles he was offered “got more limited. They want somebody who was the grandfather, or the father, or an elderly neighbor. They’re not going to be the main character, because the main character is going to be younger,” Kubota explained. “Aging actors tend to be supporting actors.”

That’s not the case with Out of Time, which was conceived by director Les Waters (he/him), who last directed Dana H. on Broadway and who was artistic director of Actors of Theatre of Louisville from 2012 to 2018. Waters was inspired by a dance piece by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker he saw in February 2020 in which the dancers were older than the norm. Waters took the idea to NAATCO co-founder Mia Katigbak (she/her), who at 67 is acutely aware of the challenges facing older actors.

“The misrepresentation of old people onstage goes hand in hand with the misrepresentation of us as Asian Americans,” Katigbak said. Indeed, the feeling of being invisible and sidelined is a common struggle of both Asian Americans specifically and senior citizens in general. To Katigbak, the notion of showcasing older Asian actors excelling at their craft took on greater urgency last year, during the rise of the Stop Asian Hate campaign. (Statistically, Asian elders are at higher risk of violence because they are seen as easier targets.)

The monologues in Out of Time, commissioned from a panoply of Asian American writers, don’t explicitly address the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes. Above all, what Katigbak wants from the project is to remind viewers that the stories being told by older Asian actors can also be universal. “NAATCO has always been focused on reshaping or reframing what’s universal, because I think universal tends to be white—white people always embody the universal,” explained Katigbak. “We can embody the universal as well. So seeing each monologue as a very specific story told by an Asian American person, I think all of them are relatable to humanity.”

Waters and Katigbak collaborated on the selection of writers for the project, settling on Jaclyn Backhaus, Sam Chanse, Mia Chung, Naomi Iizuka, and Anna Ouyang Moench. Katigbak noted that all of the writers are under the age of 60, but said this was purely a coincidence.

“We kept thinking, ‘Oh, my goodness, we should have somebody who’s over 60 represented,’” Katigbak said. “But this is the sad thing: There are not a lot of Asian American playwrights over 60s, because for a long time Asian Americans couldn’t get produced,” Katigbak says. It’s true: Aside from big names like David Henry Hwang, Philip Kan Gotanda, and Jessica Hagedorn, there’s a limited number of older Asian American playwrights still plying the trade. Added Katigbak, “We were also kind of mindful that this is a great opportunity for younger playwrights to get work seen and done.”

Katigbak and Waters gave all five playwrights the same simple prompt: The monologues had to be at least 20 minutes long and written for a performer over the age of 60. The writers were otherwise unconstrained in content and form, and what they delivered varies in topic and style. Yes, there are monologues that address death and loss. But there is also a monologue about the dissolution of a friendship; another monologue about an older writer/public intellectual who has gotten “canceled”; and another monologue that takes place in 2050.

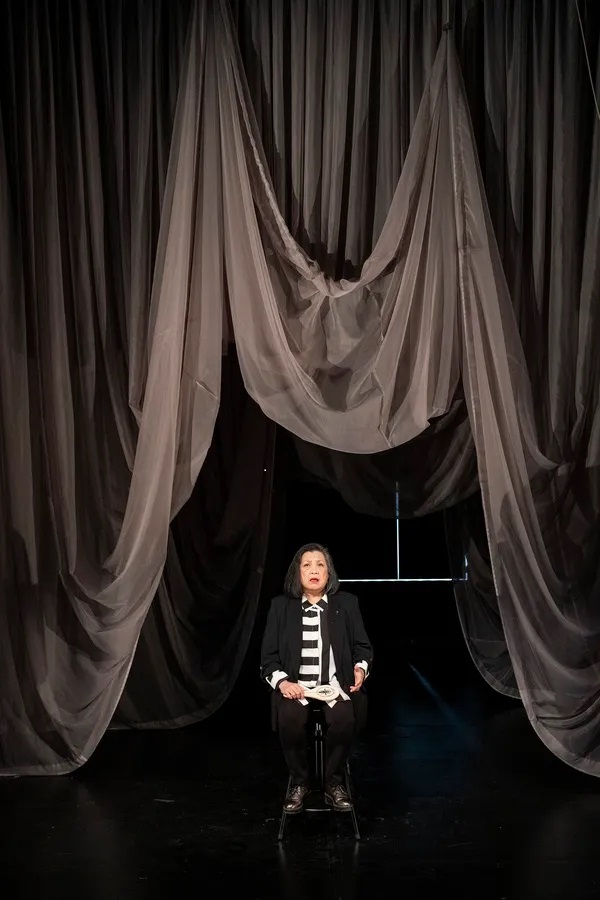

Mia Chung’s monologue—Ball in the Air, which Katigbak is performing—is a nonlinear meditation that combines the breakdown of a relationship with the 2016 election, in which the lead character discovers that her spouse isn’t who she thought he was. Both are connected to the central theme of a reality you thought you knew falling apart, and how destabilizing that feeling can be.

When she got the prompt, Chung actively resisted writing a monologue about death or illness, the usual topics when seniors are involved.

“Older actors, basically, you have a few choices: You either sit in the back and have Alzheimer’s, or you’re in a hospital bed hooked up with an I.V. and people are coming to fight over the will,” Chung said, quickly adding, “I have no judgment against those things. I just don’t believe in relegating people according to age to a certain number of topics.”

Indeed, though Chung’s monologue could arguably be performed by a performer of any age, having an experienced actor like Katigbak perform it in Out of Time is particularly thrilling; besides being a pioneer in Asian American theatre, Katigbak is also an icon of the New York experimental theatre scene. “This feeling like you can’t trust not just information, but also people—there are certain personal memories or certain stories that come to mind that someone who’s 80 or 40, like they can all draw on them,” said Chung. “And someone who’s older has more to draw from.”

Naomi Iizuka’s monologue, Japanese Folk Song, performed by Kubota, does deal with death, but in an unexpected way. It is about her father, Takehisa Iizuka, who died in December 2020 after being ill with a lung disease called cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. In the monologue, Takehisa (whose nickname is Taki) looks back on his life, telling the audience about all the times he almost died, including when a bomb fell on his house in Japan. Taki also talks about his love of whiskey and cigars and his hatred of jazz, which Iizuka’s mother loved.

Iizuka admitted that in the earliest draft of her monologue, she was influenced by the memories of her father at the end of his life, when his prolonged illness made him more angry. But Iizuka soon realized how common it was for children who care for aging parents to dwell on those difficult last few years, and to forget that their parents were once young and full of life.

“While that anger was really understandable and true in the last months of his life, that really didn’t capture who he was for most of his life,” said Iizuka. “I don’t think that’s how he would want to be remembered. He was so charming, opinionated, idiosyncratic, funny. And he really was the guy that, you would go into a party and people would sort of be gathered around him.”

Iizuka shared photos of her father with Kubota, and would answer Kubota’s questions about the elder Iizuka, such as his personality and biographical details. “Glenn is nothing like my father,” she said, “but it’s really uncanny how much he is channeling my father.” The process of working on Out of Time has also helped Iizuka grieve, especially since her mother died last year. “This was a gift, to be able to spend time with my father and his memory in this way,” she said.

Kubota admitted that Iizuka’s monologue has been a special kind of challenge, because he’s never performed a monologue of that length before. And at his age, he confessed, “Learning lines is going to take more effort, because your brain synapses are not working as well as you were when you were 20 or 30 years old.”

But when asked how he was able to channel Taki in a way that even Iizuka approved of, Kubota said it’s something he’s learned over his career about how to build character.

“When I first started out in the business, I used to be really about the details,” he said. “Like, I would sit down and I would write a biography of the person, where he was born, what his family was like, what he did in the early life, his middle life, his professional life. And then I would break down all my scenes into beats and have each beat have an objective and an obstacle. But as I got older, it just seemed like I didn’t need to do all that. I just needed to read the script, get a sense of what he was saying and what he was about. And just be yourself, and less self-conscious about getting things right.”

Kubota then offered a piece of advice that could apply to any actor, regardless of age: “Onstage, it comes across better because you’re not trying to be somebody else. You’re just yourself.”

Diep Tran (she/her) is the former senior editor of this magazine. She is currently a contributor for Backstage, The Undefeated, NBC Asian America, New York Theatre Guide, and other publications. Follow her on Twitter @DiepThought.

Creative credits for production photos: Out of Time, written by Jaclyn Backhaus, Sam Chanse, Mia Chung, Naomi Iizuka, and Anna Ouyang Moench; directed by Les Waters, with scenic design by dots, costume design by Mariko Ohigashi, lighting design by Reza Behjat, sound design by Fabian Obispo, dramaturgy by Sarah Lunnie, and production stage management by Kasson Marroquin