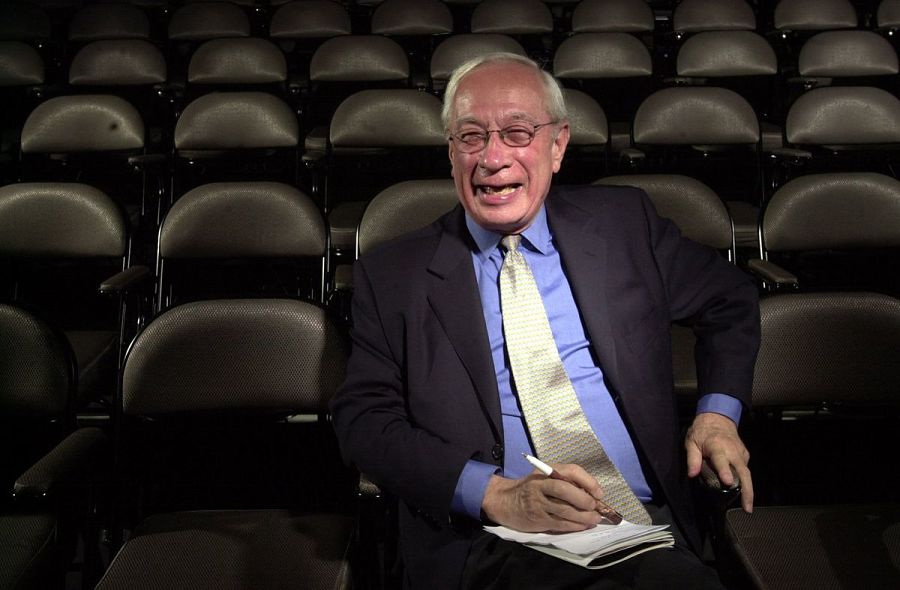

Richard Christiansen died Jan. 28 at the age of 90. The conventional brief obituaries will note that he was the former critic of the Chicago Tribune and, before that, the Chicago Daily News. That’s accurate. But it doesn’t begin to convey the degree to which he helped shape theatre in that town during his tenure of nearly four decades.

A story about Barbara Gaines suggests the larger truth. Barbara began as an actress with very little in her bank account. “My big hope then was to be a good enough actress to stay out of restaurants as a waitress,” she told me. But she also had a passion that she shared with the late Joyce Sloane, a producer at Second City. “I went to Joyce and said, ‘I can’t believe that Chicago doesn’t have a Shakespeare theatre.’ Joyce said, ‘You can have the smaller space of Second City for two weeks for free.’” Gaines put together an evening. “There were 40 actors on the stage. It was just a workshop. Scenes and monologues with music in between. Middle of January. Three feet of snow. Richard Christiansen came and covered us. He wrote a piece that said, ‘No city worth its salt can call itself a theatre city without a Shakespeare theatre.’” Barbara decided to call him and thank him. “I was hesitant, because he was a critic who sometimes reviewed my work as an actress.” Richard invited her to lunch.

“Toward the end of lunch, the waiter served some chocolate mousse. A spoonful of mousse was literally on the way to my mouth when Richard said, ‘Barbara, what did you learn?’ I said, ‘Gee, I don’t know.’ He said, ‘You learned that the next time you direct something, it has to be a full-length play of Shakespeare. That’s what you learned.’ That spoon went down on the plate, and I didn’t pick it up again because I was so nauseous. I had asked all sorts of people to be the artistic director of a new Shakespeare company. I didn’t know that I was going to do it. I didn’t even know what an artistic director’s job was. He changed my life.”

Gaines went on to found Chicago Shakespeare Theater, currently housed in three built-from-scratch, state-of-the-art spaces on Chicago’s Navy Pier. Her company received a regional theatre Tony in 2008.

How about another story? A group of young actors decided to form a company. They built a modest theatre in the basement of what had been the Immaculate Conception Church and School in the suburb of Highland Park. They struggled for a while, putting up show after show, usually paying themselves nothing because there was no money to spare. Word of their work got to Richard, and he checked them out. On May 18, 1979, he wrote about their production of The Glass Menagerie. Here is some of that review:

This is not a gentle, wispy interpretation. It is jagged and harsh in many scenes, spooky and quirky in others. Yet it strikingly illuminates the poetry of the play by casting it in a different light, re-examining its humanity, and dispelling some of the false illusions that have surrounded it in past presentations.

I saw the show on a Sunday evening (Mother’s Day) when there were only 20 customers in the troupe’s 90-seat basement space at 770 Deerfield Rd. in Highland Park. It’s amazing, and depressing, that this gifted troupe, consistently interesting in its work, was able to pull so few people into so fascinating a production.

The “gifted troupe” was Steppenwolf, and Richard’s notice prompted several people with serious money to offer their support and help move them into Chicago proper. In the years that followed, they produced legendary productions of True West, Balm in Gilead, and The Grapes of Wrath, which then went to New York and were met with raves, making stars of much of its company, including Joan Allen, Terry Kinney, John Malkovich, Laurie Metcalf, Jeff Perry, Rondi Reed, and Gary Sinise. Steppenwolf won its regional Tony in 1985.

As one of the original members of the playwrights ensemble at the Victory Gardens Theater, I was particularly aware of how crucial Richard’s support was to that company, not to mention me personally. My first production was on Victory Gardens’ second stage in 1979. Porch opened in the middle of a blizzard that was as bad as any I’d seen growing up in Chicago. I flew in to see a dress rehearsal and was floored by how good it was, but depressed at the thought that surely nobody would be foolhardy enough to brave towering snow drifts to see a show by an unknown playwright. Richard did brave that weather to cover the show. His review was so enthusiastic that—snow and ice be damned—the run sold out instantly. Victory Gardens added seats to the theatre, extended the run, and that summer reopened the production on its mainstage. It was the beginning of an association with the company which continues to this day. And I too soon got an invitation from him to lunch.

Not that the friendship that began that day kept him from occasionally giving me disappointing notices. On the one hand, I would have liked better reviews for those shows. On the other, the fact that he would write his mind honestly reaffirmed the value of the good reviews.

Victory Gardens hit a patch when its board went renegade and tried to move us into a much larger venue. Richard knew that the artistic leadership at the time—Dennis Zacek, Marcelle McVay, and Sandy Shinner—viewed this move as a threat to the theatre’s mission to focus on new American plays. He subtly let it be known where his sympathies lay, and that bad idea went away. A few seasons later, in 2001, Victory Gardens was awarded its regional theatre Tony. Richard had nominated it.

I can only begin to list the artists and works Richard supported at key moments. For example, in one 1993 review he wrote: “If you can stomach its ugly nudity, flagrant violence, foul language and blatant sleaze, you’re in for one tense, gut-twisting thriller ride in the theatre…[I]t’s an astonishing piece of work, not only for the skill of its craftsmanship but for the kinks and depths of characterization that Letts has created for his bizarre tale.” That’s right: While the other critics in Chicago were close to unanimous in their disdain for a play they found offensive and nihilistic, Richard saw in Tracy Letts’s debut, Killer Joe (featuring a young, unknown Michael Shannon), the writing talent that would later become undeniable in August: Osage County. And yes, Richard invited Tracy to lunch too.

In 2010, when Victory Gardens built a new second stage in the Biograph building (the home to which it moved in the wake of the Tony win), artistic director Dennis Zacek tried to find a corporation or rich donor to pony up enough money for the naming rights. Nobody stepped forward. It was suggested to him that, if it wasn’t going to bring in any money anyway, maybe he should do a good thing and name the space for Richard, in recognition of his contributions not only to our company but to the Chicago theatre scene in general. Dennis mulled this over for a bit. One day he found himself sitting in Chicago’s Arts Club with Richard, and he asked him how he would feel about the idea. Dennis tells me that Richard’s eyes instantly filled with tears. To a reporter seeking a reaction, Richard said, “I’m tickled pink.”

The Tribune reported that among the Chicago theatre veterans who sent checks in Richard’s honor were David Mamet, Rick Cleveland, John Logan, William Petersen, John Mahoney, George Wendt, Michael Shannon, Deanna Dunagan, Tracy Letts, and Joe Mantegna, “as well as a who’s who of Chicago-area artistic directors.” Dennis says he doubts that even if he had been able to sell naming rights to a corporation that the total would have matched the almost $300,000 that the Chicago theatre community donated.

By that point, Richard had been retired for nine years. When he announced his retirement from the Trib in 2001, several theatre companies contacted him with the idea of sponsoring celebrations. I don’t recall which companies he said yes to. I do know that Second City, the famed house of improvisational and satiric comedy, decided to host a roast. I called him afterwards and asked, “What could anybody possibly have roasted you about? Your taste in ties?” Richard chuckled and said he wouldn’t share that with me. I told him I had my sources. So I called up someone who was there. An actor told me, “We all realized we had nothing of consequence to roast him about, so we got up and read the worst reviews we’d gotten from him.”

In 2004, he published a book called A Theater of Our Own: A History and a Memoir of 1,001 Nights in Chicago. In it he described many of the performances he had caught and covered in more than 40 years of reviewing. Typically, he downplayed his own role in the story he told. You won’t find an account of the lunch he had with Barbara Gaines in his memoir, for instance, or of the innumerable lunches he had with many of the rest of us.

I once interviewed him about his relationship with the community he covered. Here is some of what he said:

“I remember years before I even thought about spending most of my professional life as an arts reporter, I read a piece reporting that the Broadway theatre community threw a party at Sardi’s for Brooks Atkinson, who was about to retire as the theatre critic for The New York Times. All the stars he had reviewed for years came out to salute him. The article said that it was on that occasion that he met all of them for the very first time. He had never socialized or had any communication with them in any form before then. I remember thinking that was quite amazing and, at the same time, something of a shame, because he missed out on the pleasure of some very good company.

“I never really had that goal of distancing myself absolutely from the people I would be writing about. But I didn’t really have much choice. On almost all American newspapers, the reviewer is also the reporter. In addition to writing about the plays, you’re responsible for reporting on news events in the theatre and also to do advance stories and interviews and so on. In doing that, naturally you come into contact with people you’re eventually going to be reviewing. It’s a situation ideally you would not have—you’d have your reviewer on the one hand, and someone else would be the reporter and do the advance pieces and interviews.

“But I got to talk to and know a lot of the people in the community. I don’t know that I would have wanted it any other way. I learned a lot and had a lot of fun. I always tried—‘tried’ I think is the important word—to keep a careful balance, walk a fine line between knowledge of the community and wholesale buying into it. Of course, the person who writes the review is not a member of the theatre community. He’s a member of the audience and stands outside looking in. But sometimes, on occasion, you walk inside and get to know the theatre. There’s a great danger: If you get to know a theatre too well—for example, if you’re doing an advance story and you talk to the director and actors and designers and they’re all passionately committed to the project and you go see it—you’re in danger of reading into it all their passion. You’re not coming to it as fresh as one should as a member of the audience.

“It’s much more delicate in a community like Chicago, where everybody sort of knows everybody else. You track people’s careers and you follow their work. But I’ve always found a generous attitude in the Chicago theatre community—the feeling being that the reviewer can certainly be wrong (and he will be kicked around for it), but if the mistake is made without any kind of hidden agenda or axe to grind or obvious prejudice, you can be forgiven. [The artists] can forgive if they know, as a rule, that the reviewer is generally bright and his heart is pure.”

Those of us who had the benefit of his support, guidance, encouragement, and analysis will attest that hearts don’t come much purer.

Jeffrey Sweet (he/him) is a playwright and the author of Something Wonderful Right Away (about Second City) and The O’Neill (about the Eugene O’Neill Memorial Theater Center). He serves on the Council of the Dramatists Guild.