Not all paths through theatre education are made equal. Jennifer M. Holmes’s father grew up in Coventry, England, and served in World War II. After returning from service, he started taking elocution classes and happened to be spotted by acting scouts. After auditioning for and attending the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, he performed with the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Old Vic before moving to the U.S. when Holmes was 12 and taking on Broadway.

“He was a really big inspiration for me,” Holmes (she/her) said. “In a lot of my work, I’ve worked in spaces where young people haven’t necessarily had access to theatre or theatre experiences. Or I’ve worked in places where maybe they didn’t think this could be their career. I think a lot about access in terms of the opportunities that were afforded to him, and obviously that I’ve had in my life, because of somebody who believed in him in this elocution class.”

Holmes’s mother, meanwhile, grew up in the U.S. and had a different educational experience in theatre—an experience more akin to “look to your left, look to your right, one of you won’t be here.” Unlike her father, her mother wound up leaving the business, taking with her many strong feelings about the field’s shortcomings in managing artists’ mental health.

“They fueled both my love for theatre and also an interest in mentorship and education,” said Holmes.

It should be no surprise that Holmes’s career has since taken her up the educational ranks, from an adjunct at Pace University teaching world drama, theatre history, and acting, to associate dean for academic affairs at the New School, to dean of the College of Arts, Communications, and Design at Long Island University’s Post and Brooklyn campuses.

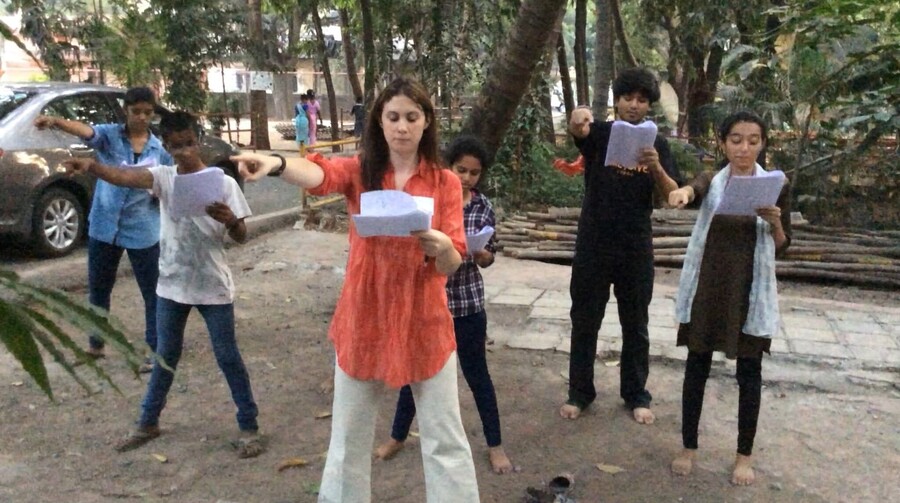

Most recently, Holmes was named the new executive director of Pace University’s Pace School of Performing Arts. In addition to her experience in the U.S. education system—which includes a B.A. from Vassar College, and an M.A. and Ph.D. from New York University—Holmes co-founded Global Empowerment Theatre, an international nonprofit theatre organization.

One experience at a Global Empowerment Theatre workshop has really stuck with her. Working in Zanzibar with a group of young people who didn’t really define themselves as actors, she met a young woman who had been very quiet; one teacher told Holmes they’d never heard her speak. But on the third day of the workshop, that young woman wrote a story and asked to perform it.

“She got up and she did it with so much energy and excitement and so much joy,” Holmes reflected, noting that the students and teachers leapt to their feet in applause afterwards. “It was just this wonderful moment of how theatre is for everybody—that everybody can tell a story, everybody can get up and do a beautiful piece of theatre, and that it’s important that we engage communities in this work.”

Earlier this week I had the chance to talk to Holmes more about her vision for Pace moving forward and how her students will be prepared for an evolving field.

JERALD RAYMOND PIERCE: Looking back on your parents’ theatre background as well as your previous positions at Long Island University and the New School, what are you taking away from those experiences and hoping to give the students in your new position at Pace?

JENNIFER M. HOLMES: I’ve been thinking about two things: innovation and access. I think we’ve experienced that a bit with COVID, where we’ve moved from, “Gosh, I don’t know if we should stream theatre,” to streaming theatre because it makes it more accessible. We think about it in terms of, what do we need to prepare our students for what the profession is not, but what we would like it to be? What voices and content are we valuing? What does it mean to have the canon? What is “the canon?”

We’ve been doing things the same way for a long time. The performing arts in general as a profession, but also in the educational sphere, is really having a reckoning moment. It’s one of the reasons I’m so excited to be coming back to Pace, because I feel like Pace is this wonderful institution that is at the crux of the beginning of an artist’s journey. It’s located right in New York City. A lot of our students perform and work while they’re in school, while they’re taking classes. There’s all of this connection with the artists directly working in New York City, and I think we’re all having this moment together. It’s a really important and exciting time to think about how we can innovate, and how we can make sure that there’s access for more people, so that they can become artists, so that they can have voices and leadership, but also so that we can make sure that the stories we haven’t been hearing get told and get heard.

I also have been thinking a lot about it in terms of the digital space. There’s been incredible strides, before the pandemic and during, with stagecraft, VR, AR, and thinking about the ways in which theatre artists can have an impact on that world and the ethics of it. But also, from a performing arts perspective: How are we telling stories? How are we creating worlds? What do we want those worlds to look like? What does that all mean? That’s been very interesting to me as well. And thinking about it also in terms of, artists really need to be creating their own work. So how can we encourage young artists to also be the content creators, and not just the interpreters of the art form?

As you’re talking about how we’re looking at the future of the field and how the field’s evolving, what’s the key to a program being able to keep up with those changes? I feel like the stereotype for academia is that it moves pretty slowly. How do you keep pace with a pretty quickly changing field?

Well, I’ll say, Pace is exciting because I’ve seen them do it. I actually started my teaching career at Pace, and that’s where I first was an adjunct faculty member, so it’s really been a bit of a homecoming for me. I was there right on the crux when it was a theatre department, and then shifted into what is now the Pace Performing Arts School, which is just a huge and exciting place to be. But it came from a small department. The faculty are very creative, they’re very innovative, they’re very engaged. They’ve already created so many incredible programs, such as the acting BFA in film, television, voiceover, and commercials—that didn’t exist until very recently, and it’s the first of its kind—and our production and design program.

It’s really about collaboration and getting together with the community, with the faculty, talking to the students, talking to artists in the professional world. I’m often talking to other artistic professionals and saying, “Hey, what’s missing? What was missing from your education now that you’re here in this moment? What do you think is missing in terms of where we need to go next, what is lacking?” So it’s really about the collaboration and discussion, and then it’s action. You do have to move it forward, and yes, a university has a lot of moments where you need to deal with bureaucracy.

But I have to say I’ve been very impressed with the president at Pace [Marvin Krislov]. I arrived mid-November, and I would say I’ve probably met with him more than I have met with leadership in some of the other institutions I’ve been in. He’s very engaged in moving things forward to the next level, and that’s important too, because one of the things I’ve learned through my work, whether it’s in equity, diversity, and inclusion, or whether it’s in curriculum development, they all go together. Or whether it is coming up with new policies and procedures, you really can’t do it alone. We’ve already started making some additions and some changes to the curriculum, and thinking about new degree programs and ways to bring in new technology. So from the moment I started, we’ve already been having these conversations. I’m hoping, in the next one to two years, you’re going to see some major changes at Pace that are super exciting.

I was reading that you redesigned the curricula at the New School. Is this going to be a similar process?

I hope it’s similar in that it went quickly there. So, yes. I tend to work collaboratively anyway. I approach the classroom, and my work as a director, and my work as an administrator, in the spirit of collaboration. I always come in almost as a student myself, because I feel like I’m there to learn and listen, and to work with everybody to come up with something that we can all be excited about. I think when you’re in a leadership position, or if you’re a director or a faculty member, at some point you have to say, “Here’s how we’re going to move ahead and move this forward.” You’re always learning and listening. I think that that is why the curriculum development that I did at New School was successful. It’s why some of the curriculum that I developed at Pace still exists there, because I was there when we were shifting from the department to a school. And I love it, so that helps.

When it comes to institutional changes, it feels like every leader in the university setting at this point is dealing with the same question on how to create an environment where students, especially students of color, feel safe to grow as artists. How are you approaching making sure Pace is able to be a safe space for artistic expression and growth for the future students of color?

Absolutely. I’ll say that I prefer the word “brave” to “safe,” because I’m not sure, in what we do, we can ever fully be safe. But I want everyone to feel like they can be brave in the room. Political activist and theatre director Augusto Boal said that change is not risk-free. We have to all be willing to really have the difficult conversations, and that’s not risk-free. That has to be brave. It’s so systemic. You can’t undo 400 years of inequality, undo years and years of oppression and issues in our performing arts world and in our country, with just a few meetings. It’s a journey.

This is going to be ongoing in terms of some of the things that I think need to be done. We need to really embed this work in the curriculum. We need to look at the content and the voices that we’re privileging and how we’re teaching. We need to embed the training with anti-racist practice, with consent culture. It has to be in the classroom and it has to be across the board. I think it’s not enough to train just the faculty; I think we have to train the students how to be in the room together, and how to collaborate together. It’s also about having equitable and clearly communicated transparent policies and procedures.

It’s about listening and believing people’s experiences, and saying, “I hear that this is what you’ve experienced,” because what I find is sometimes challenging is a lot of people doing this work say, “Well, this was my intent, and I tried this, and I’m a good person.” It’s not about that; it’s really about the impact. We have to believe that this is what people are experiencing, and we need to trust them. We need to trust ourselves to move forward, and be brave together.

It feels like, especially over the last few years, internships and the entry level of the theatre field has been on shaky ground. We’ve even seen programs intended to lift new voices, like the Lark and Lincoln Center’s Directors Lab, go away. As you work with students on how to be in the room together, and prepare them to enter other rooms after graduation, how are you thinking about preparing them for the current professional landscape? Has your outlook on how you need to send students out into the world to find those early entry-level ways to get into the field has changed?

I think we need more support for that kind of mentorship. Mentorship is on the list of things I’d like to see happen more [at Pace]. It’s a way to engage with our alumni community. We have so many incredible alumni out in the field, whether they’re working in stage management, or design, or on the screen, or on the stage. And I think that our students coming into the field could learn a lot from that mentorship.

They’ve had to navigate these rooms and spaces. They are invested in the school, and they’re invested in their career. These students really can benefit from having those kinds of mentors to show them the ropes and to invite them into the rooms. I always think that any time I get a chair at the table, I want to pull up five more.

Is there anything else you’d like to tell our readers?

It’s been a bit of a marathon, COVID, and the finish line keeps moving. In March, we were told it would be May. In May, we were told it would be the end of August, and then after the vaccines, and then Delta came, and then Omicron arrived, and all these letters of the Greek alphabet keep adding another mile to the marathon. Legend has it that the messenger for whom the marathon was designed was delivering [the Greeks] a message of victory, and then he collapsed and died. It killed the original runner after 25 miles! Then [at the 1908 Olympic Games in London] Queen Alexandra decided to add another mile after the first guy died—she added a mile so the race would end at her Royal Box. So it led to this tradition where marathon runners will shout, “God save the Queen!” as they pass the 25 mile mark.

I think we keep being told that this is it, and then someone or something tags on another mile to the race and we have to renew our hope and energy. You just have to lace up your shoes and keep running. I think performing arts is very much like that. It’s a constant renewal of energy. It’s grueling, inspiring, unexpected, but you have to keep renewing your energy and pushing forward. As you were saying, both in the professional landscape and in the educational landscape, we have a lot of work to do to innovate, to move forward with courage, to be equitable and inclusive, and I think this is a journey and you don’t ever reach the finish line. So I think we all have to lace up our shoes and just keep running.

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is associate editor of American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org