The 39th annual Humana Festival of New American Plays, hosted by Actors Theatre of Louisville, ran through April 12, with five fully produced world-premiere plays and a series of 10-minute plays. For those who have never attended, it’s a bit like the Sundance Film Festival for theatre, only with better bourbon.

As part of our special Humana coverage this year, we’ve been interviewing the playwrights. Previously, we talked to Erin Courtney, Jen Silverman, Colman Domingo and Charles Mee. We caught up with Pig Iron Theatre Company‘s Dan Rothenberg during Humana’s closing weekend—but no worries, I Promised Myself to Live Faster will return to the troupe’s Philadelphia home in May (details below).

LOUISVILLE, KY.: For this year’s Humana Festival, the prop shop at Actors Theatre of Louisville was tasked with building a lot of dildos, which showed up as decorative pieces on staffs, furniture and guns for Pig Iron’s newest work, I Promised Myself to Live Faster.

“What the props and lights and set departments did for our show was the Lord’s work,” said an impressed Dan Rothenberg, Pig Iron’s artistic director and the director of Live Faster. “They’ve made many dildos for us, with a lot of jokes on an e-mail thread that 37 people are copied on about ‘why the dildo’s breaking.'”

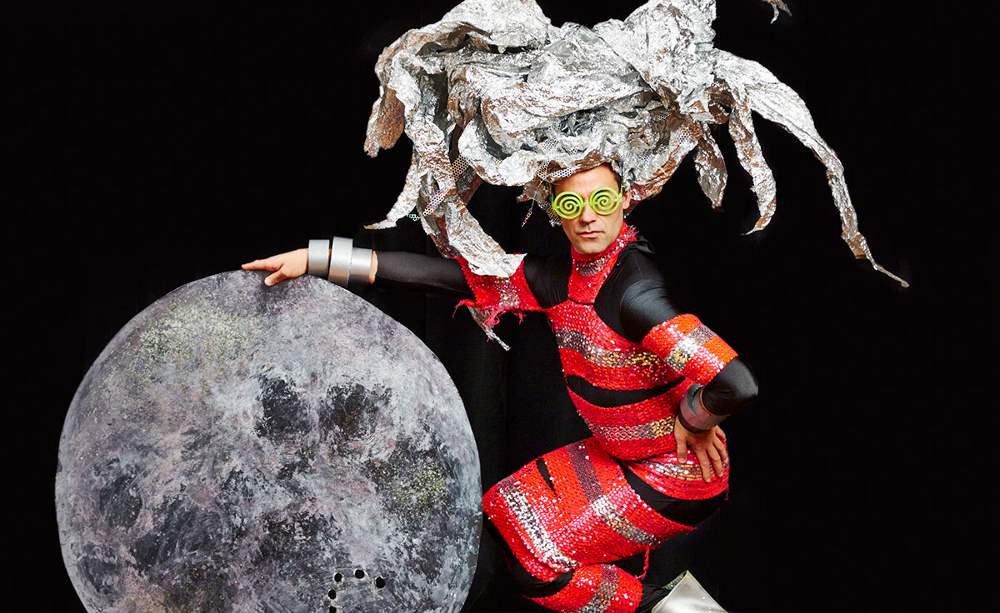

A five-foot dildo staff was among the least jaw-dropping elements of the show, which featured drag queens, Grindr and sexy space aliens as plot devices. The devised piece—directed by Rothenberg, with text from Gregory S. Moss and the Pig Iron company—is a science-fiction adventure that follows the recently dumped Tim, who must travel through space to retrieve the Holy Gay Flame. His failure could mean the extinction of every homosexual in the universe.

We spoke to Rothenberg about what this out-of-this-world story is really about and about the company’s techniques for mixing the perverse and profound. I Promised Myself to Live Faster just finished its Humana run and will travel next to Philadelphia, where it will play May 22-31 at FringeArts.

What was the genesis of this idea to make a gay sci-fi fantasia?

We’ve been working on this play for almost five years, in small dribs and drabs, for a week here and a week there. Over the past decade, Dito van Reigersberg, one of the founders of Pig Iron [and an actor in Live Faster], had this amazing other side of his artistic career where he is Martha Graham Cracker—that’s his drag persona. Unlike some drag queens, he doesn’t pass. He’s got plenty of body hair, so he’s called the tallest, hairiest drag queen in the world. And he sings, live, so he doesn’t lip-sync. And so the origin point was: What if Martha Graham Cracker was in a Pig Iron show? Martha Graham Cracker exists in this world of cabaret, but could we put her into a show?

The other point of origin is the stories of the Ridiculous Theatre Company. We’re a little too young to have seen the Ridiculous Theatre Company, but there were stories of it that my high school drama teacher told me. I then repeated those storiesto Pig Iron—about these legendary performances of Camille, about these plays falling apart, about this controlled chaos, and especially about people crying in the audience because Camille is dying and then there’s this famous exchange: “Throw another faggot on the fire,” “There are no faggots in the house,” and Charles Ludlam going, “No faggots in the house?” with a wink into the audience and everybody erupting into laughter.

So if you can think of that as a formal concern, in terms of being able to turn on a dime and really make the audience laugh at how stupid everything is, but also make them care and cry…I can keep going.

Please do!

The connection to sci-fi actually came from a very small biographical detail, which was that Charles Ludlam grew up across the street from a movie theatre, and he watched these movies of the ’40s and the ’50s, and we saw how those movies really imprinted him as a preteen and became the fodder for his work.

We were talking with Robert O’Hara, who was one of the dramaturgs for the piece, and Robert was talking about the ’80s, and how Ludlam kind of existed in the ’50s in our imagination but he was also in the ’80s. That connected to our own imprinting of certain movies from the ’80s, like The Last Starfighter and Star Wars, and “Star Trek” as well. Sci-fi was originally called “space operas,” and they are big, sprawling melodramas. So I feel like the secret heart of the show is the connection to sci-fi and the erotic life of an 11-year-old. If that makes sense.

We talked a lot about being 11; 11 stood in for this moment in life, the moment where you start to have enormous sexual tides, where your whole consciousness changes but you’re not ready to have actual contact with a person. And so you sort of project these feelings of longing and rescue and despair onto these big melodramas. You can’t really talk about or really understand the desire to have sex with another person. But you can talk about the unfairness, that he can’t be with her in outer space and that the Rebel Alliance is struggling against the Evil Empire. You can talk about that and you live your erotic life through that.

And that that’s a moment for queer people of having to sort out, which character am I among all of that? The moment of knowing who you can to have sex with…sci-fi is sort of the perfect vessel for those longings.

How do you find the balance between the profound and the…

Throwaway and funny? I feel like the play is rooted in grief, and a few different kinds of grief: the grief in America and in the gay community about AIDS wiping out a generation of gay artists and gay practices, bath houses and everything like that, and this other grief of contemporary culture and the Internet changing what gay culture is today. In literal economic terms, gay bars are shutting down all across the country. Why? Because of Grindr, and because you don’t have to find a secret place to be with people like yourself. It also leads to splintering in the queer community because you’re able to shop online. And that’s great! That’s a huge civil rights victory in my lifetime. But from a cultural point of view, there’s a sorrow that goes along with it.

When you’re doing the play for audiences who aren’t as used to all the cultural reference points you’re citing, how do you make sure that the audience understands everything you’re trying to tell them?

I think a show like this, which is, in quotes, theatrical, relies on a knowing glance at the audience. So even if they don’t know, they think they know, and they just want to be part of that interaction.

But there are references from the ’70s and ’80s that people born in the ’90s have no response to. We also did a lot of test audiences and we said, “So do you know what Grindr is?” to older folks. And they said, “No, but the way you put it together, I understand what it is—a gay dating app with pictures. I understand.”

So I’ve been really pleased at how many different ages and audiences are dealing with it, both gay and straight, both old and young. And it’s been surprising: Older audiences have been much more into it than I’ve anticipated. They’ve had a great time laughing at people licking butts. To their and my surprise.