A version of the following was delivered as a speech at the 2019 Imaginate Festival in Edinburgh.

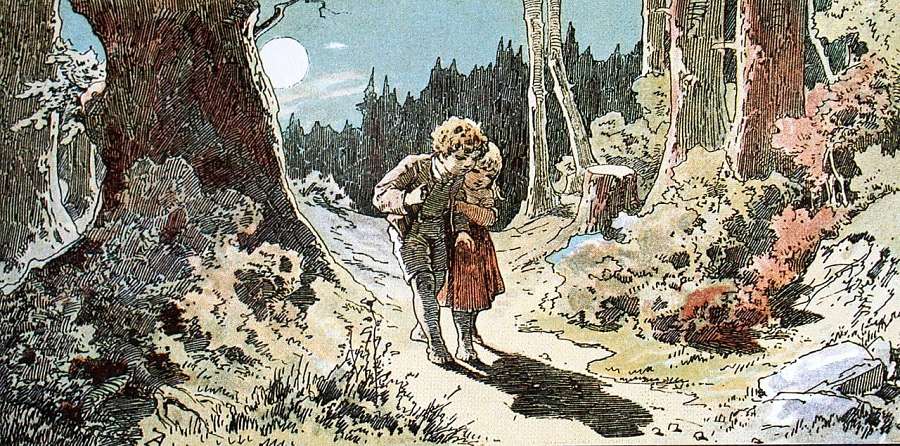

When sitting down to write this talk, I quite arbitrarily decided to call it “Hope Is a Trail of Breadcrumbs”—a nod to some key imagery in the folklore that’s inspired me, and whose conflicts sit at the heart of so much modern Theatre for Young Audiences.

But then pretty shortly after choosing this title, I realized the inherent problem in it—which is the fact that the metaphor is a tricky one, because it actually means two oppositional things.

Sometimes we use it to denote a solution, because Hansel left the breadcrumbs as a link between points A and B—between being lost in a tundra and returned to the warmth of a home: “I left a trail of breadcrumbs!”

And other times it’s used to denote a frustration, because the birds ate those crumbs. Because the boy’s logic was flawed and suddenly the distance (between dark, anonymous woods and warm, reassuring cottage windows spied after a long journey) was all the greater: “I left a trail of breadcrumbs…”

But then pretty soon after realizing this problem—of a muddied analogy when a clear one was necessary—I realized that in fact the conundrum was perfectly fine, and indeed relevant.

The trail of breadcrumbs was a reassurance for our abandoned siblings. When all was going wrong, when they sensed that this journey into this forest held dark intent, the breadcrumbs offered possible salvation. Not a guaranteed one—a possible one.

And it’s an often forgotten fact that only one chapter earlier in the very same, still so famous story, Hansel enacts another strategy—which is to lay a trail of white pebbles behind him and Gretel. And that plan works. That time, they do get home. But we don’t (in our day-to-day conversations) talk about that plan. The imagery of a “trail of white pebbles” hasn’t entered the collective consciousness as a metaphor for hope.

But the breadcrumbs—they are the analogous touchstone we seek. Because we are not thinking of them as the failure they were. We are thinking of them as the salvation they might be, the tools of a plan that might work. And the “might,” it is mighty. The might—it is hope.

❦

Many children’s stories today, whether played out in theatres or picked up off bookshelves, seem to have been fashioned from white pebbles. They introduce themselves to their young audience at the beginning of a journey, they lay the safe white pebbles through the journey, and at journey’s end (just as promised, just as could never for a second be doubted), they follow them home.

And the journey is the journey. The artist’s flights of fancy are the artist’s flights of fancy—these we have no right to question. But the choice of material—the decisive future-proofing of the white pebbles, the assurance of safety, the sidestepping of risk—this may need pause for thought.

Because the world is not necessarily like this. Or (and arguably more importantly) while it may be like this for me, it could very easily not be like this for you. To place a work of art before a grand, sweeping audience of children and their adults is to guarantee yourself a great variety of perspectives: of lives lived, of circumstances known, of psychological rigors not politely left at the theatre door by each child as she enters, but carried into the room, and sat upon her lap, and picked up and used as a pair of binoculars through which she might then view the play that plays out, the art you or I made for her, for him, for them.

We cannot speak for each of these personalities, and so we must respectfully speak for none. We must craft a story of variables, of risk and reassurance, of rickety bridges and looming towers and comforting hearths and bucolic clearings, of schoolyards populated by friend and foe, of dinner table conversations imbued with knowledge and ignorance, of good mornings and bad, clear skies and cloudy, of roads with multiple paths diverging, of ill winds, of breadcrumbs. Because in this convoluted landscape, therein lays the hope.

And when I think of the most respectful, and so most satisfying TYA work I’ve seen, a commonality is that those living out their lives onstage are unlucky enough to be provided with no clearly marked journeys. And are lucky enough to be provided with no clearly marked journeys. So that what remains is the hope.

❦

And today, right now, hope is what we need. Today we are fortifying—on the edges of our lands, on the inside of our minds. We are making hard decisions about hard borders with hard hearts. And if a society chooses to do this, it may slowly (so slowly it itself doesn’t even notice) grow unhealthy. But it’s this glacial degradation of empathy that I believe art has the power to, in some small way, affect.

Because in its basest form, a story, a play is an exercise in placing oneself in the shoes of another. And for some strange human reason that clever people may understand and I do not, we know this innately, in a hardwired manner that cuts through personal bias or childish naïveté—if the offering’s well-constructed enough, the young first-time theatregoer will know what to do. And more importantly, the value-hardened cynic will know what to feel.

So the experience becomes hopeful, an incremental step toward what I believe every single person actively treasures or secretly yearns for—which is a sense of community. And what theatre does manage to do, is actively engage us in a central, and very hopeful, premise of community. Which is a lot of people caring about the same thing at the same time.

Other pursuits do this too, of course—such as sport, very successfully. But the distinction in my mind is that standing in a stadium is about a shared investment in people whose talents eclipse our own. The role of an athlete is to be best at a thing, and what we marvel at is the superhuman. But sitting in a theatre is about a shared investment in ordinary people, placed in complex situations. What is marveled at, then, is the super humanity.

That story can, for a young person sat in a theatre, act as one formative breadcrumb in a long, hopeful trail through life’s woods. And the birds may come. The path may prove less linear than imagined. At times the forest may loom and the shadows may be long. But all those things are external. What really matters—in the ability to deal with a play, in the ability to deal with a life—is the internal: the resolve and the resilience and the love and the empathy and the hope, of that child, and eventually of that adult they become.

❦

I write about hope a lot, in the plays I try to create for young audiences and older.

In one, Simon Ives lives an overscheduled, 12-and-a-bit-year-old life and wishes for a moment of calm. Meanwhile at the furthest edge of the universe, the titular Boy at the Edge of Everything lives in total solitude and wishes for the opposite: a community to engage with, a population to be part of. And when the two happen to meet (due to a shed of fireworks exploding and Simon being shot into space), the Boy at the Edge of Everything explains to him that out of that everything, out of every single planet in existence, he’s chosen to spend the past few billion years focusing on Earth, for one very simple reason:

I did see it come to be, Simon Ives, one millennia when I was up on the roof. I saw gases and chemicals merge, forces pull things together. There are quite a few planets I’ve seen turn up, over the years, but this one—it caught my eye. It just looked so…hopeful. It wanted to work. So after that I kept checking in on it, every few centuries.

Soon mountains and valleys formed—water drove its way up through rock, plants drove their way up through water, grew onto land. Forests! They were beautiful. Things began moving, on the surface, things that took on many forms (have you ever seen a giraffe? That thing is hilarious). Dinosaurs came along—they were great. Your ones—the beginnings of you—they appeared. And they had hope too!

They started off cold, but they found fire soon enough. The fire melted things into points, the points cut wood, the wood made structures, the structures gave shelter, the shelters held farmers who told the land what to be, held teachers who told the children what they could be—they passed on the hope!

And the children became adults…and the hopes became realities! I saw dams and bridges and skyscrapers and aeroplanes and…these small screens, which…which could see you saying hello in one place—and then show you saying hello in another! Between people who…who could be way away (on the edge of everything, say) and still feel connected. If they wanted to. When they were ready to.

This one little blue and green planet…With all those people. All that hope.

And you miss those faraway people, Simon Ives, because you lost them. But I miss them too… Because we never even got to meet.

That monologue casts a very literal bow across the evolving of us, and the earth beneath our feet, naming hope as the fuel for that evolution. But more broadly than this, I believe all my writing, and indeed all of any of our art-making (whether intentional or not), is an existential exercise in hope.

Because we cannot make art without acknowledging the world. Indeed, we cannot exist in the world without acknowledging the world. We are the product of a culture’s moment in time, its place in the world, its seat at a dinner table, its biology. So that life around us, our communities, its highs and lows, has osmotically been stitched into the fabric of what we make.

And life around the audience will osmotically color their sense of what they see, and inform the brand of hope with which they enter. If the world outside the theatre on this night is, for whatever reason, feeling like a menacing woods to a child, and the world onstage is a comparative warm hearth, then they will hope for a substitution—for this to cancel out that, a brief hour of forgetting.

And if the world outside the theatre is for that particular child the warm hearth, and the story onstage is the tragedy, then they will hope for more of what they have. And empathetically—because people are really pretty good—they will hope for the play’s protagonists to know that warmth too. They will acknowledge their luck at their life, and cross fingers that the show’s characters will eventually know it too.

And this is the crux of the beautiful investment between maker and viewer. An audience watching a well-shaped play will ultimately hope—for the sake of fictitious characters, who they have known only a few minutes—that the birds do not come. That the breadcrumbs stay lying right where they are.

And even if they know the story, even if what they’re watching is just a new telling of old tropes, then the audience will hope that the birds do not come this time. And even if they do come this time, then the audience will hope that what happens next has a better outcome than the one they remember. And on and on and on with the hoping.

A child audience that is respected, that’s provided the permission to act as it wishes, that’s given not sure white pebbles but flawed, fleeting, ephemeral breadcrumbs (visible from the air, scrumptious to birds) can, if trusted, do wonderful things. Or terrible things. Or anything it wishes. Because in truth, our hope isn’t only that the child watching won’t become a victim of complex emotions. But also that they won’t become wielders of them.

A last aspect of hope I want to discuss, and one that ties back to Hansel and Gretel and their plotting, whether with pebble or crumb, is the far too common misconception today that hope must relate only to something ahead of us. Of course the act of hoping—the notion of something sat upon the horizon—suggests a later encounter. But the thing being encountered (being found, achieved, fallen in love with) can actually be historical, or be right here and right now. As much as the future, our hope can be born of the past, and the present.

And I say this because it’s so easy, and so common, to aspire. To set one’s sights on a greater wealth to come, on a wiser age to be, on a new love to woo, on a new you to evolve into. But the truth is so often the epiphanies we have, whether hoped for or stumbled upon, actually hold not new but retrospective value.

Hansel and Gretel, our bread-toting protagonists, dream a dream that lies not ahead but behind them—a dream of going home.

But so many works for children are dedicated to the idea of aspiration. They invite a young audience to be hopeful, yes, but direct that hope only forward, only towards a thing not yet attained, a thing they will one day be.

And this isn’t just in theatre, but in life too, as we suggest a child’s significance is one in development, as opposed to one existing right now. A child as eventual effective citizen, as future audience member—as though they weren’t actively inhabiting a seat, in a theatre, in this very second.

A child is asked far too many times: “What are you going to be?” But a child—the one I remember being, the one I’m currently raising and loving and so observing most closely—doesn’t give too much time to this. He exists (just as I did) largely in the here and now, sometimes in the life to come, but often in the things that were. And his hopes reflect this.

He hopes for a variable right this minute, like the sun coming out so we can lie in the hammock and read books, or like a mate dropping by to play. He hopes for something far in the future: like one day driving a car or growing a beard or meeting a robot. And he hopes for things grounded firmly in the past: like seeing a beloved relative again, or returning to a place he remembers fondly.

And although only 6, he is accruing a pretty good sense of time and how it works. But that isn’t at all to say that he respects it. Some days he’d like to just go back in time to revisit things missed. Others he wishes to extend a good moment, or skip over a bad. Some days he wants to be a man already. Some days he loves being a kid. Some days he tells us his memories of being a baby. Others he can in no way believe he was ever that small.

He, like so many children, loves dinosaurs and hoverboards equally. He knows one is extinct and the other a prototype, but to him these aren’t wildly divergent states of being. They are both things not in his immediate grasp, but which are no less exciting or hopeful for that fact.

History, he is learning, is just as subjective and imaginary as the future. It changes form, based on how we are feeling in the moment we consider it.

❦

I will add an ending to my ending, a short epilogue, by saying that this talk is not only a story, just as no story is ever only a story.

Without meaning to bore you with detail, two years ago my family and I moved home. After 15 years spent growing up separately in Adelaide, and then 15 more spent growing up together in Tasmania, my wife Essie and I felt it was time to close a circle and return.

So the following of breadcrumbs back to familiar, and familial, doorsteps actually bears the comforting weight of autobiography. But what the real-life narrative reveals, which maybe the fairy tales do not, is that of course the wild woods are not necessarily bad places. They are more often than not wonderful ones, fearful only in their ambiguity, pleasurable in their discovery—sites for life, for love, for adventure, for risk and for reward.

Their long shadows intimidate us as we enter, but they have to do that. If they forewarned us of their makeup, then they would not be wild woods, but something safer, a flat open space, a landscape of white pebbles maybe.

And what the great tellers of the great folklore knew, and have tried to tell us time and again (since children first sat in theatres, since clans first sat round fires), is that we need both: the warm hearth and the wild wood. We need the risk and the reassurance, the years of being raised, and then the years of being brave, and finally the years of being calm.

And if we just know it’s a circle when we leave (if the ending is guaranteed at the beginning, the white pebbles already calling us home even before we truly call ourselves away), then the journey into the wilderness is not really that. And so the pleasure of eventual return is not really that either.

But if we can step trepidatiously into the wild woods, alone if we must, or holding hands with another if we’re lucky—if we are laying hopeful breadcrumbs behind us, but not presuming to be wiser than fate, not presuming to be in control of the birds and their appetites, the heavens and the seasons and the currents and the years, then we are truly adventuring.

Then one day we will return of our own volition, with a deeper voice and a calmer mind and a love that has known many years and a child that is only knowing his first ones. And stories to tell. And stories to hear.

To me that is a great, and a very current pleasure. It is the child of risk, of breadcrumbs and, more than anything, the child of hope.

And for me, were there ever a theatrical story to tell, or a real-world life to live, this one is it.

Finegan Kruckemeyer is a playwright based in Australia. His previous piece for American Theatre was “The Taboo of Sadness: Why Are We Scared to Let Children Be Scared?”