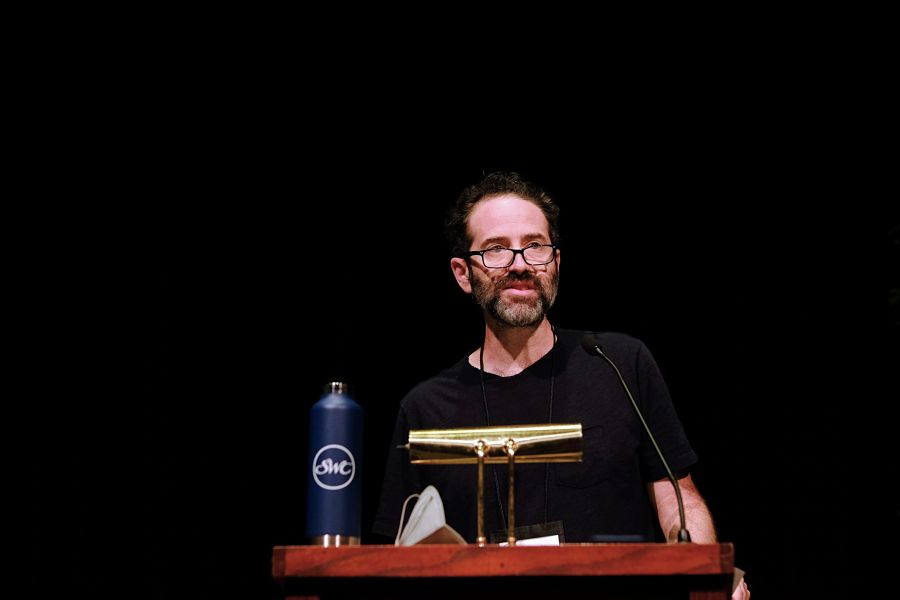

A version of the following was delivered as a lecture at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, held at the University of South in July, and portions of it were adapted from this piece in The Stage. This piece is part of a season preview package.

If you have survived cancer—if you have survived anything, including COVID-19—then you are intimately familiar with the problem of second acts. You question why you are here when others are not. You worry that the crisis is not passed but lying in wait, ready to recur. You find yourself attempting to master your trauma in memory (and in writing), thereby paradoxically fanning its flames. You wonder, as playwrights often wonder as they pause upon the plateau of a competently written first act, what can and should and must come next. The middle, you see, is a muddle.

During my treatment for stage 4 colon cancer in 2016—an ordeal that commenced on the very day my wife concluded her treatment for stage 2 breast cancer—I wanted nothing more than to “get back to normal,” the day-to-dayness of a husband and new father, a mid-career playwright and poet. At the same time I wanted desperately to revise my life fundamentally, irrevocably, to “burn it all down”—i.e., any and all aspects of my life before cancer that had failed to bring me enough health and joy. I devised innumerable plans for reconceiving my career, my relationships, my psychology. I envisioned a better life—better than normal. You could say I wished to move backward and forward at once: back to the relative safety of the past, and ahead toward a post-traumatic reinvention of self. In other words, I was conflicted. Yet conflict can be constructive, as every playwright knows: it heats and hammers and forges, if we are lucky, a new life.

❦

To speak of second acts is to speak of acts. Or action, which is what happens. How you choose to organize what happens is your structure. Dramatic structure, then, is the shape of what happens.

A handful of fundamentals: Acts run anywhere from 20 to 60 minutes; anything shorter belongs in the sub-genres of the “short play” or “10-minute play.” An act may contain one or numerous scenes, clearly numbered in the script, each set in a different time and/or place; an act can be composed of many so-called “French scenes” in which time and place is stable while characters come and go, each new configuration of personae constituting a new scene. (These French scenes are never numbered.) Dramaturgically speaking, an act is a unit of action in which characters are propelled and compelled from a point of calm through a phase of “rising action” (more on this later) to some climactic shift in circumstance—what Chekhov termed, with vaudevillian panache, the “punch on the nose.” A plot twist, then, is a sucker punch. A playwright’s biggest punch is the knockout that effectively ends the play.

Play structure is act structure is scene structure. Like fractal patterns in nature, a play’s shape is reiterated within its acts, scenes, and momentous beats. (I know a much-lauded director who will swear up and down the theatre bar that the first page of every “great play” contains, like a seed, like the golden ratio, the structure of the play as a whole.) This rudimentary structure is recognizable as the line graph we recall—with horror and humor—from high school, though these days it may remind us more of COVID-19 infections and deaths. In both the scientific and the dramatic the x-axis is time, but in the play our y is danger. The line itself is conflict.

There are phases of progress. The curtain rises on the status quo, an enactment of what’s normal in your characters’ lives. Exposition is forgiven here. All manner of tensions ripple the surface, but the play hasn’t properly begun. The status quo may last five minutes or 15, though modern playwrights tend to sketch the everyday, or allude to it without depicting it while confronting straightaway the problem of the play. This true beginning, whenever it occurs, is the inciting incident: something a character says or does, or a crisis imposed from without, that sets the play’s clock ticking. As Robert McKee defines it in Story, his influential (if Byzantine) how-to for dramatic writers, the inciting incident casts the protagonist’s life into disarray, and the narrative that unfolds is the play-by-play of their attempt to “get back to normal,” or—perhaps ideally—to discover and achieve a new normal, a new life.

After the story’s launched, we follow a trajectory referred to regrettably as rising action—regrettable because it makes me think of bread baking and Viagra. But “rising” surely refers to blood pressure generally and heart rate and horripilation in the audience as the play’s conflict complicates and intensifies. Despite variation in pace and tone from scene to scene, a traditionally structured play rarely retreats from danger to safety.

Eventually—again, a bit too comically sexually—we reach climax. Many have noted with a wink and a critique the maleness of the single-climax structure. But traditionally structured plays accumulate many smaller climaxes along the way. In a scene a climactic beat is often referred to as an “event”: Conflict between characters has wrought a change, a noteworthy development that establishes a new status quo for the increasingly perilous conflict ahead. After the play’s final climax—that knockout punch, remember—a period of “falling” action ensues, a scene or scenes in which themes and plotlines are tied up neatly with eloquent summations and lessons learned, etc. This resolution or denouement is, in its way, yet another status quo, which is why endings are also beginnings.

There is of course much more to say about the traditional or conventional or “well-made” model of dramatic structure, but Wikipedia is there for you, for all of us. And I’m not suggesting you write your play this way—far from it. But more of my backtracking after a break.

I am thinking about structure, and in particular second acts, for personal reasons. I am middle-aged, you may be surprised to learn. Middle age is the height of uncertainty. Gone—far gone—are the quasi-delusional convictions of my 20s. At the same time, I’ve yet to achieve the resignation, the liberating acquiescence and grace of older age. (Wisdom is coming, right?) As I grew older I had trouble accepting that I was leaving the boisterous town of my youth for the dark woods of midlife. I still have trouble accepting it. Because routinely I feel 12 years old again, still—the age at which I witnessed my brother’s suicide attempt when he leapt from a window in our attic, or younger, maybe three years old in moments of joy and rage and wonder, of pure presence. Most of the time I am probably around 30, or whenever it was that I first hit my stride as that universal prosaic type, the Adult.

Maybe you feel similarly. But then the years flit past, you’re changing incrementally, in temperament and body, shuddering through the bumps and scrapes of careers, the complexities and negotiations of intimacy and family—until inevitably you collide with some immovable obstacle. An accident; you or a loved one falls ill. War or pandemic erupts. Thus interrupted we are devastated, dislodged from the well-made structures of the lives we believed we were living, and we are bewildered, panicked to find ourselves lost in that dark wood, having wandered from the straight path. Or jettisoned from the path, like my wife and me—the path itself obliterated. Left staggering through a blasted no-man’s-land.

In the middle of drafting this lecture I took a few days away for my regularly scheduled CT scan. As I write this I am awaiting the results. I am approaching the five-year anniversary of the end of my cancer treatment, during which I time I have lived without “evidence of disease”; my oncologist will use the term “permanent remission,” sometimes even the word “cure,” if someone like me survives 10 years without a recurrence of the cancer. I am roughly halfway to survival.

I am in the middle in so many ways. The second half of this lecture remains to be written. There are plays to complete, poems to revise, books to publish and sweatily self-promote. I have a seven-year-old daughter to raise (and I am determined to do everything in my power, such as it is, to shield her from the trauma I knew as a child). I am in no way finished with my story. But I am not the ultimate author of my life. The results of this scan may not make sense, structurally speaking. It may transform my private drama—my comedy, on good days—back into the tragedy it seemed to be five years ago. Or into something worse: a story without meaning.

But sooner or later the call comes. Late in the day as I’m out for a run in the Southern California sun. I lower my mask. I stop and stand still, steeling the quaver in my voice: “Hello?” The results, the nurse says, are normal. The scan is “clear.” I now have another year before another reckoning. I have found my feet again, or I have been allowed (by what? by whom?) to find the path—a new path, not the path I was following before cancer—lit up again with the purpose of my second act. I resume my run.

❦

Now let me apologize for all of that talk of Viagra and Chekhov and traditionally structured plays. I don’t write that way—or not exclusively.

I received my Master’s of Fine Arts degree in a program in which the concept of “structure” was almost taboo. And I wanted that; I agreed. I was at a lecture once where the playwright Mac Wellman was fielding a graduate student’s gotcha question. “How do you define dramatic structure?” Mac paused for dramatic effect. “Dramatic structure,” he said, “is that way in which your play’s structure resembles the structure of an older and better play.”

Our philosophy then, in a nutshell, was that mainstream models of structure are derivative, constrictive, deceptive, biased, and often just plain boring. I thought of myself as an experimental playwright—at 23!—or a formally challenging one, at least. I wanted to tell stories the way I wanted to tell them, not out of hubris necessarily, but in pursuit of verisimilitude. If the most dramatic passages in our lives are tumultuous, disordering, confusing, how can a truthful play tell a straightforward story?

Then as now we had political objections too. Cognitive structures are inherited and often exploitative; in dramaturgical terms, a play’s structure aims to exploit resources of attention and emotion. As with structures of law, of policing, so it is with arts organizations. The structure of a nonprofit theatre—its artistic staff, board, subscribers—all but dictates which plays and musicals are produced; values expressed and encoded in these chosen works are implicitly sanctioned. Many of us are skeptical of structural power of every kind, so why should we not question, deviate from, or reject the tenets and proscriptions of the modern well-made play?

I am by nature skeptical. Or maybe it’s nurture’s fault, having been raised in a house where our behavior was harshly regulated for inscrutable and pathological reasons. As a child I suspected every rule was an unjust attempt to control me.

My skepticism toward conventional forms of dramatic structure is also no doubt related to my obsessive-compulsive disorder, which blossomed in my adolescence in the spring after my brother’s suicide attempt. Many of my obsessions had to do with form: I arranged objects in my bedroom, for instance, in superstitiously significant, often symmetrical patterns. Pens on my desk. Pin-badges in my lampshade. A postcard from Sunday school listing in order the books of Bible had to be placed on my nightstand leaning upright just so, and if—God forbid—a careless turn or wayward draft sent it fluttering to the carpet below, I would have to snatch it up immediately and replace it with grinding consternation, just so, then kneel and lace my hands and pray for forgiveness. And the prayers themselves were intricately structured (by me) and repetitive. It was exhausting.

But even in the throes of my distress, I knew that my beliefs and behaviors were ludicrous and arbitrary. The structures I was endeavoring to impose upon myself and my environment would have no effect on the disaster I was subconsciously dreading (a second suicide attempt that would succeed). Yet I went on organizing my life in this way because I was conjuring for myself the illusion of safety. It was not long after I developed OCD that I began to scribble in my notebook, and I was amazed to find that when I let myself write freely and honestly—that is, dangerously—my symptoms eased. Writing without rules was showing me the way, the straight path, it seemed to me then, toward freedom and health.

In graduate school, however, many of the freest, least rule-bound plays I was reading and seeing (and writing) didn’t make much sense. Or not enough sense—to me. They evaded or deflated the clichés of experience, yes, but was that enough? The playwright seemed to be hiding in the play; I couldn’t figure out why this story mattered to them, to say nothing of why it mattered to the characters, if these actor-automatons could rightly be called characters. (Another slogan among my cohort: “Character is dead,” whatever that meant.) These plays flattered my intellect sometimes, but rarely roused my empathy. I felt left out. And my alienation seemed to prove that there had been a failure of the theatrical compact, in that a play should be as natural as conversation (albeit a temporarily one-sided conversation).

Secretly I began to feel like the Neil Simon of the department. I had recently returned from a wanderjahr in Ireland where I’d been studying, informally and frequently drunkenly, with oral storytellers. Despite my proclivity for innovative storytelling, I wanted my plays to communicate—to connect. Remember I was still that child who felt he could only speak through poems, stories, plays. I hungered to be heard. So I decided as a young playwright that I would give traditional forms another, and ongoing, appraisal.

There are many reasons why a playwright may wish to employ or borrow from received notions of dramatic structure. As a result of history’s trial and error, these models are sturdy and reliable. You’re not wasting your one wild and precious life laboring to reinvent the wheel. You are giving the audience what they want—and why not? What have you got against them? You comfort the audience by meeting many of their expectations; they are primed for the familiar, while anticipating subtle yet meaningful deviations. You stand a better chance of reaching a wider audience with your modern well-made play produced at large regional theatres, Off- and maybe on Broadway, which may in turn foster opportunities in TV and film. You could end up earning a living.

And writing within well-made confines doesn’t have to be solely or predominantly about comforting the audience; the elegance of traditional forms can elevate horrifying subject matter, and focus overwhelming material of any kind into a cogent dramatic thesis. Historical and political plays offering solutions and indictments can benefit from these clarifying forms.

I know what I’m doing isn’t new; like most writers, I’m attempting to make the old new again. Just as the young feel that they are inventing love and sex (they are), as the middle-aged are inventing divorce and death, I believe with every new play that I am inventing for myself the craft of playwriting. I place myself in the middle and synthesize. I write out of a creative tension, an inner conflict between reaching the audience and expressing my idiosyncratic self. I err on the side of unease. My hope is that the unfamiliar in my play will shake the audience awake, and in this way affect them more deeply than the play they were drowsily expecting.

❦

No matter your approach, the question remains: Why are second acts so hard to write? Because it’s easier to make a mistake than to make amends; because possibilities are generative whereas resolutions reduce.

Playwrights know that Act Two pivots upon the climax of the preceding act. We find our new bearings and a more difficult struggle—an enlargement, an entanglement of the original predicament—and proceed hazardously from there. Our most common error is a second act that suffers from sameness; not enough pivot, too much continuity. Or in a related sense, our second act circles round and retraces the trajectory of our first act, producing a story that’s too controlled and therefore contrived. Another mistake is to hurtle ahead with the abandon of our first act’s exploration and to lose our plot, like Ahab in the “unshored, harbourless immensities.” A second act insufficiently related to its first will abandon the audience and dispel their empathy.

The challenge of the second act, as I have come to see it, is to yield to the play that our play is becoming. We allow Act One’s crisis, catastrophe, revolution, what have you, to alter the structure of the play drastically, if required. Ideally we accept that the writing of Act One has changed the playwright—our premeditated design for the play but also, perhaps, our preconceptions about ourselves—and for this reason the play we finish is not the play we set out to write.

This is how it has been in my life. I feel continuity with who I was before cancer; but I am also drastically changed. If my life’s second act began the afternoon I was unhooked from my final dose of Fluorouracil, then my objective these last five years—not only to persist but to remake myself, to invent a new self who is surviving the particular calamity of cancer—has drawn me into many unforeseen conflicts: the conflict of keeping calm, of pursuing and enjoying joy, of creating the conditions for optimism, as well as more practical questions, like, how will my marriage mature, how will I parent now, how will my new writing communicate and for what reasons? My overarching objective now is to make meaning out of what my wife and I have been through, so that I might feel that our suffering is worth something—not commercially speaking, certainly, but another kind of worth I do not have the words for.

Where we are as a theatre culture today feels very familiar to me. For more than a year now, furloughed, forgotten, exiled in a state of suspension, theatre artists have been ruminating and reflecting, and a multitude of structural sins that we may have tolerated previously are now rightly considered appalling. We have wanted to work. We have missed the camaraderie of rehearsals, and the dark, sealed container of a theatre crowded with warm and breathing bodies, caught together in the spell of a communal imagining. Yet we are hungering for—we are demanding—an industry transformed, a theatre culture worthy of our dedication.

The Trump era flared out in a one-act of stupidity and carnage; with vaccines, and theatres reopening indoors, we are all now wading into a morass of unwritten potential. Will the theatre regress, out of habit (or tradition), fear and the assumption of economic necessity—a shameful dud of a drama, if it happens—or will we strive toward new structures and the new health that in our convalescence we imagined?

The stakes could not be higher. The art form has been hemorrhaging talent to other genres, other livelihoods. If we fail to achieve something like herd immunity here in the U.S., or, failing that, a low-enough incidence of infection, won’t partially filled theatres only foster more elite audiences, due to higher ticket prices and preshow prerequisites like tech-based vaccine passports? Won’t producers feel the need to provide these privileged audiences with more cautious fare, revivals and classics, and new plays and musicals that affirm rather than confront the audience’s complacencies and prejudices?

I fear the dismay, the malaise that will descend if our lives in the theatre “go back to normal.” Not improved. Not better. Not burned away, purged and reborn, but merely…resumed. Or can things be worse than before? Because after trauma there often arises an equal and opposite urge to pretend that nothing much has really changed. To quarantine our pain, to cordon disaster in a corner of our subconscious and to forget. Or to try to forget, as repressed emotion invariably manifests in destructive if not psychotic fashion.

Our dreams of massive institutional metamorphosis may indeed seem to evaporate, at first. Because it was a dream. Change that happens fast is one of our most cherished dramaturgical fantasies. The task of our post-pandemic second act, if you will, is to take action and, because it will take time, hold fast to the hard-won insights of 2020, when our objectives were clarified and amplified: Theatres need diverse leadership and staff; plays and musicals must enact the stories of the population at large, not solely those of the theatre’s wealthy patrons and corporate donors; artists deserve something remotely approaching a living wage. The list goes on.

What is possible now—what has already been occurring—is the creation of accessible theatre, presented inventively. Streaming productions should continue for those who cannot afford the journey or the price of admission. Much has been and will continue to be staged outdoors and in unconventional settings. Many artists have little left to lose—so they are taking risks. We may be witnessing the reemergence of a truly nonprofit theatre. That said, a demotic, grassroots movement may do nothing to rectify the economic exploitation of artists. But it may cultivate more pertinent storytelling and a genuinely popular theatre in the years ahead.

As mentioned earlier, during the depredations and isolation of my cancer treatment I wondered if I wanted to keep writing at all—if writing had been a choice to begin with. I could make that choice now, I reasoned. I could shut up. Or I could write solely for myself, for my desk drawer, and find another career. This might have been my version of burning it all down. But I am stubborn, and I remembered why I wrote my first play. So I chose to return in my recovery to the wellspring of my passion. I would write only what I wanted to write, what I needed to write, now with all the force and candor I could muster. I would be—because I had to be—less afraid. Because I had lived beside the abyss of meaninglessness and loss, as we have all been living for some time now, I would not abandon my art but seek to challenge and change it. I would trust, as I trust now, that my second act—as long as it lasts, as long as it takes—will lead to a better life in the theatre.

❦

I was going to end there. With that punch on the nose: a real-world application of artistic introspection. But I’d rather conclude in the classical mode: We are unified, here in this place, a theatre, in this time now, the summer of 2021. We are surviving. We are lucky to be here.

We are told that we have gone back to normal. Or getting there. Our status quo regained. We are post-COVID—or getting there, perhaps getting there…We are cancer-free, or that’s the hope, anyway. I can’t help but recall my return to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference in 2017, just months after treatment, when I was confused and terrified. Astonished. I was grieving and rejoicing, rejoicing and grieving. All at once. But on the whole my joy was winning and leading me forward. Helping me find my way and tell my story. So I feel that now with you. I feel it keenly because in a theatre at play we are never alone. We are in this together.

Dan O’Brien is a writer whose works include the play The Body of an American, the book A Story That Happens: On Playwriting, Childhood, & Other Traumas, and the poetry collection Our Cancers. His most recent play, The House in Scarsdale: A Memoir for the Stage, won the 2018 PEN America Award for Drama.