Micki Grant—composer, lyricist, playwright, librettist, actress, singer, dancer—racked up many firsts in her long career. She was the first woman to write and star in a Broadway musical (1972’s Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope), and the first female author/composer to have two musicals running simultaneously on Broadway. She was the first woman to win a Grammy Award for the score of a Broadway musical, and the first Black person to get a contract on a television soap opera (she played the role of the attorney Peggy Nolan on Another World for seven years).

In addition to her work onstage and screen, which included five Broadway productions and 20 theatrical productions overall, she served as national chairperson of the Equal Employment Opportunity Committee of the television union, where she worked diligently to increase employment of minorities in television.

I had the pleasure to begin a series of conversations with Ms. Grant as she was approaching her 92nd birthday (in June of this year). The process with her was an ongoing adventure: Sometimes she was ready and other times she would say to call back. There was never a dull moment, even when she did not want to share. She was crafty, mischievous, and full of pranks. At one point she told an aide who asked who she talking to that I was her husband. And she was forever telling me to call back, that she would have more to share. I was planning to do just that, but she died before I could, on Saturday, Aug. 21.

Our last conversation was on Aug. 1. The following has been edited and condensed from our various conversations.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: You graduated from Englewood High School in Chicago. Were you active in theatre there?

MICKI GRANT: In fact, I was already involved in theatre before high school. We had a little theatre group in the neighborhood, and I was taking what they called, at that time, dramatic lessons. The teacher’s name was Susan Porche; she was really dramatic herself. This is how dramatic she was: The rest of her family pronounced it “porch,” but she was “por-shay.” She took me on even before I was in my teens; she just saw something in me, and she taught me poetry. Every other week or so my mother was taking me someplace to speak on a program. I was coming along at a very early age. I knew where I was going.

Your church was responsible for publishing a book of your poems (String of Pearls; 26 poems) when you were a teenager. What would you like to share about that experience?

I was a book person, with me walking around holding a book. There wasn’t anyone around like me in my neighborhood at my age. I guess it made me kind of special. Because I had been writing and reciting poetry for so long, what it ended up being was a collection of those things, all in one piece. When I went to speak at places, I also had the poetry. There is a story about it that I don’t like to tell. It has to do with a big suitcase full of my poetry being thrown on the garbage truck. [Long pause.] I had a suitcase at my brother-in-law and sister’s house; I was not living in Chicago then. I had all these books in the suitcase sitting in the garage. And my brother-in-law was just out there clearing out things, and he didn’t open it to see what was in it. He just picked up the suitcase and just threw it on the garbage trunk. It was filled with copies of my books! When he found out, he kept running after it, trying to get if off the truck, but he couldn’t. He never got it off the truck. I think about it to this day. Something like that, you don’t get over it. Over a hundred of my books were thrown out. The suitcase was full of my books of poetry. Certain things happen in your life that cause you so much pain. As old as I am, I remember it like it was yesterday.

Before we talk about your connection to theatre, can you tell me about the pop song you wrote, “Pink Shoe Laces”?

I was trying to write a song, and I thought, people are writing crazy things about love and this and the other, and I wanted to get attention—I wanted to say something. I said, “What can I write that is crazy?” I don’t know why I came up with tan shoes and pink shoelaces. That seemed like the craziest thing in the world, pink shoelaces. [She starts to sing the song.]

Now I’ve got a guy and his name is Dooley

He’s my guy and I love him truly

He’s not good lookin’, heaven knows

But I’m wild about his crazy clothes

He wears tan shoes with pink shoe laces

A polka dot vest and man, oh, man

Tan shoes with pink shoe laces

And a big Panama with a purple hat band

Ooh-ooh, ooh, ooh

Ooh-ooh, ooh, ooh

And it became a big hit. I was writing the craziest thing I could think of just to get attention, and it got attention. It did not quite get to number one, but it got to number three.

Why didn’t you sing it?

Because I wasn’t signed to a record company. The person who sang it was Dodie Stevens. I sent them the song and they signed it and I was very happy. I might not have had the song if they waited for me to sing it.

C. Bernard Jackson, who was Black, and James Hatch, who was white, wrote the book, music and lyrics for Fly Blackbird after being inspired by a speech by Martin Luther King Jr. It was a biting Civil Rights satire with an integrated cast making fun of segregation with a message about integration. Your friend Glory Van Scott along with Robert Guillaume were highlighted in the 1962 musical. How did you become involved with the musical, and what can you share about that experience?

I met James Hatch and his partner, Jackson, in Los Angeles. They started the show out there. I was their leading soprano when we did it out there. They brought it to New York, but didn’t bring the cast to New York; I came here on my own. I had a friend staying on the Lower East Side. I had to audition, and although I had done the lead in Los Angeles, they only let me be in the chorus. I guess they thought we were just L.A. people, and that movie people could not act onstage.

In 1963, you made your Broadway debut as the ingénue in Langston Hughes’s Tambourines to Glory, a gospel musical. How did that happen?

Langston always said when he did a show, he wanted me in it. I was writing poetry, and of course he was a poet. [Pause] I have to go back and think about all of this. It’s almost like a whole passage of time that has escaped me. Somebody has to come and say, “Remember when you did that?” You know, I had whole periods of doing things. I went through the whole period of doing television. And then there was the whole period when I was overseas. I was in France; I was in England; I was in Italy; I was in Australia, believe it or not! I was thinking about this the other day: There are certain periods that I almost cannot remember. I have to go back with someone, if they have not left this world already, and retrace my steps: Where was I during this period? Where was I at that year? I am going to have to do all of that very soon.

Now back to Langston. Langston and I were not buddy-buddy, where we ran around together. I would go and see him wherever he appeared, and he would recognize me. He was someone I admired as he wrote poetry, and that is what I wanted to do, and he encouraged me. That’s how we came to know each other.

Did you know Lorraine Hansberry?

Oh yes, of course, we were in the same neighborhood, a few blocks from each other—down the street, in fact. We went to the same high school.

You went to the same high school with Lorraine Hansberry? Micki, I didn’t know that.

We went to the same elementary and high school. I didn’t say we were together; I said we went to the same schools in the same neighborhood. We were not buddy-buddy. She never became part of our community. I remember she came to one of our meetings—I don’t know what it was about, but we were getting together and talking about something, and she sat there and took it in and smiled and listened, but she was not a group person.

What would you like to tell me about your Off-Broadway experience in The Blacks, in which so many Black actors of your generation appeared?

I came in after several people had done it. I don’t consider that a big deal. Cicely Tyson had done it. Thelma Oliver had done it. It had been running for a couple of years when I came into it. I was just glad to get my name attached to it, since so many people had their names attached to it: Maya Angelou, James Earl Jones, Louis Gossett. It was like a beginning thing, and it ran for long time. A lot of people had that job for a long time, and it was unusual for Blacks to have a job in theatre for that long.

What about Brecht on Brecht in 1963?

I was very happy to do that because it was established with white people, so when it came out, I got such great reviews as a Black person. That was a big thing for me to be in that cast and get the kind of reviews I did.

You played roles on several soap operas: Edge of Night, Guiding Light, All My Children. You were the first African American contract player on a soap opera, as Peggy Nolan on NBC’s Another World. Did the historical significance of your achievement as being the first contracted Black player on a soap opera have any meaning for you at the time?

I don’t remember that much about all of them, but I did Another World for seven years. The reason I got it was because my agent told them I couldn’t keep coming back to town to do the show when I was getting work out of town. And when they tried to replace me, they didn’t like the people they were bringing in, and my agent said, “She can’t keep running back here every time you call. If you want her, you have to give her a contract.” So I became the first Black to have a soap opera contract.

What can you share about working with Vinnette Carroll?

It was a great experience, one of those magical things that happened. She called me about one thing, and all of a sudden she had her own place, the Urban Arts Corps, and I was doing original stuff. If you have a place to and work on original stuff, nobody is afraid to do it because of spending money. She had a place to go and work on stuff, and it ended up with her being able to do things that she wanted to, with her as the director and me as the writer. It all came together so perfectly. It was a fortunate meeting between us: I needed somewhere to present my work and she needed the new work to present because of who she was—having original works brought out her creativity, rather than trying to repeat something that was already done.

Your given name was Minnie. Why did you change it?

Because at the time everybody was always saying Minnie the Moocher, or Minnie, Minnie, the Pickaninny. And then “Frankie and Johnny” came along, and I though, Oh, she wasn’t Frank; she was Frankie. I said, instead of Minnie I will be Micki, and I will spell it differently to make it fancy. It just seemed like it was perfect for show business. You know anybody in show business with that name except Minnie Riperton?

What do you think is your major contribution to the theatre?

I was the first female to do the score of a Broadway musical, and I was the first female to do the book, music, and lyrics. The music was never done by the female. Some of the biggest names you know: Comden and Green did the lyrics, Bernstein did the music. But I always did the music and the lyrics. My major contribution—I guess Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope was the first time you had a Black musical competing for the Tony Award and almost winning it. If Stephen Sondheim hadn’t come in two weeks before [with A Little Night Music], we were about to win the Tony. You really have to ask other people about my major contribution. My major contribution would be what other people think and what they tell you.

I never saw Phillis. What can you share about that 1986 musical?

It was supposed to be a big hit. It had been a huge hit Off-Broadway. The play was going to open on Broadway. But they brought in a brand new person to direct it, a white director who didn’t even know who Phillis Wheatley was. It was the worst thing that ever happened to me in my life. I can’t even talk about it, but I have to write about it. I want everybody to know about it before I die. I want it publicized and in a book, how they destroyed this wonderful show. I want it known. I still want the play done. Everybody should know about Phillis Wheatley; she was the first published Black poet.

Can you say more about that experience?

Well, this white director didn’t even understand the play. He tried to make a comedy of it—one of those ridiculous, foolish Black comedy things they thought Black people could do, instead of the sensitive, beautiful play about this wonderful, sensitive poet, Phillis Wheatley. I hadn’t seen it—they kept me out of the theatre. When I saw it on opening night, they had to carry me out. I was sobbing all the way down the aisle, and people were wondering what was wrong with me. I could not believe it was my show. I told the critics that was not my show.

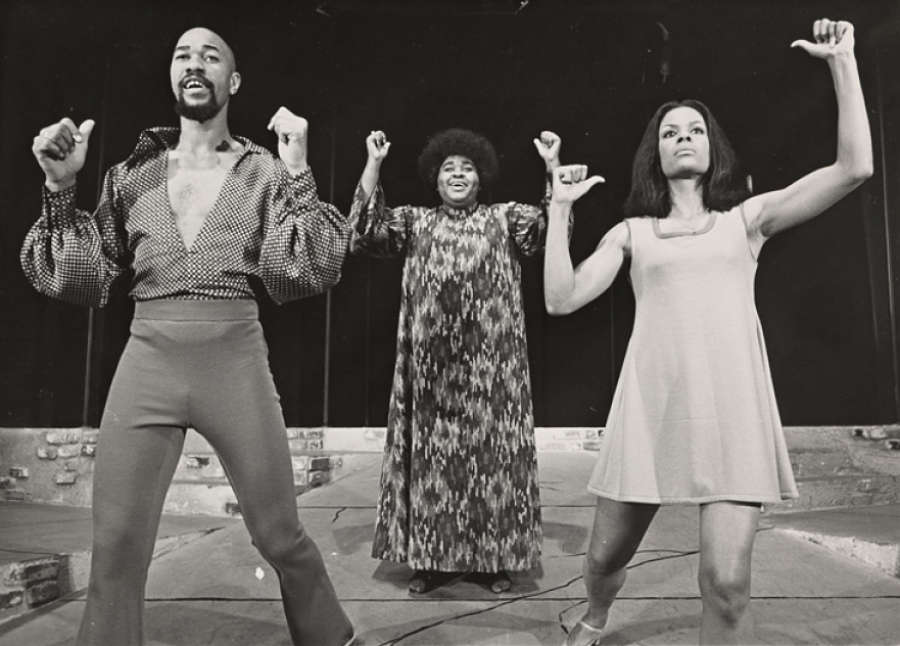

What was it like working with dancer/choreographer George Faison?

He knows who he is and what he wants, that’s for sure. In other words, you can’t put anything over on him. Of course, working with me, it is different. You know I am the one who is making it work for everybody—everybody who is there is there because I made some work for them. George Faison knows what he wants, and he will get it. And I will get what I want from George Faison.

So you guys had a difficult time working together?

Oh, no. It is exactly the opposite. I am glad you said that because you would have gone away with the wrong impression. We got along fine. He got what he wanted, and I got what I wanted. Do you understand what I’m saying? We got what we wanted because we are the kind of people we are. What he is in the community of dance, he is somebody. And in the community of theatre, I am somebody. So we were “two somebodies” getting along like “two somebodies,” not scratching or pulling hair or anything like that. We were respecting each other. Once we went to work, we just found out in one day who was in charge; it only took one day.

I read that your father played the piano.

He did play the piano, great pianist, by ear. And I started playing the piano. I didn’t end up playing the piano; my sister ended up playing the piano, and she took lessons. I would sit there and play the piano because my father did—I would play what he was playing. The minute I started to read music and knew what notes were all about, I couldn’t play by ear anymore. Isn’t that funny?

How many instruments do you play?

Probably four: the double bass, the guitar, violin—those are the two that I’m trained in. I don’t play the piano, but I know the piano, you know what I’m saying?

How did you start writing lyrics?

I always wrote. When I was eight or nine years old, I was writing poetry. There are people who were doing things since they were kids. I just liked doing rhymes and poetry. I can’t give you a reason as to why, but I did. I would be sitting at the breakfast table, and I would say, “You can pass me the salt if you please, and if you don’t want to, I can get on my knees.”

It was just natural to you.

Yeah, I just liked putting words together. I guess when I heard it being read that way and done that way, I realized it was poetry. You recognize those things when you are five years old—when you are doing your Easter piece when you are four or five. Did you do the Easter program at your church?

Yes, everyone does that.

The little kids get up and say their best poems, especially from Sunday School and all of that. We used to get up and say our poetry from the time I was a little kid, because we were always in church. You learn poetry by reading it, by being taught it, and I saw how somebody did it, so I did it. Instead of reading what somebody else wrote, I would write it myself. Nobody didn’t tell me I could; I just did it.

What is it that you want people to know about you?

I don’t know what it is that I want people to know about me that they don’t know. And the things that they do know might be things I don’t want them to know. [Roars with laughter.]

What are some of the things you don’t want people to know about you?

Why would I tell you if I don’t want them to know?

What person was the biggest influence on your life?

In my life? My life is a big thing. I would probably say my mother, Gussie Odessa Cobbins, because she never discouraged me from anything by saying, “Aren’t you reaching for a bit much?” You know what I’m saying? She took me to places when I said I wanted to join that, and I would be the only little Black kid sitting there. When I would read about something where they said they were holding auditions for something, she would take me. She never discouraged me from anything, even sometimes when it was crazy. She would say go for it.

Nathaniel G. Nesmith (he/him) holds an MFA in playwriting and a Ph.D. in theatre from Columbia University.