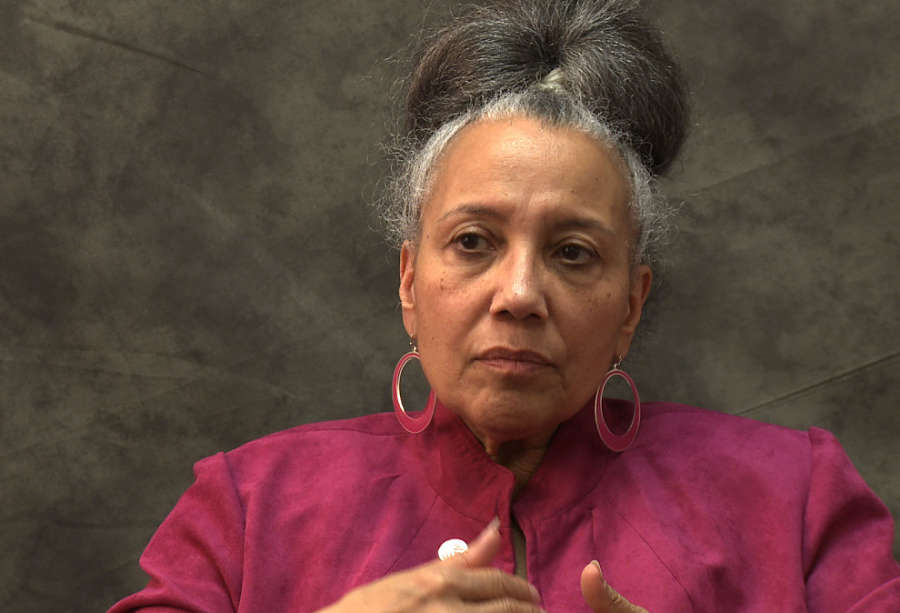

When Bob Moses, leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, recruited fellow New Yorker Doris Derby (she/her) to relocate to the Jim Crow South in the 1960s, he offered Derby, then working as an elementary school teacher, a position as a SNCC field secretary at the grand salary of $10 per week. The idea of forming a theatre, especially one that would become a cultural linchpin of the Civil Rights Movement, wasn’t yet a glimmer. SNCC’s focus was on achieving the franchise for masses of rural Black adults who faced barriers and obstacles including the one Moses wanted Derby to help them overcome: literacy tests comprising dozens of arcane and legalistic questions meant to prevent the masses of sharecroppers who worked the fields sun-up to sunset from becoming voters.

Questions like these from a 1965 Alabama Literacy Test read like truncheon blows on the body politic:

Who passes laws against piracy?

Or

The electoral vote for President is counted in the presence of two bodies. Name them:

“We were developing a specific type of literacy program,” Dr. Derby explained in a recent interview. “It was tied to being able to produce and read different information relating to voting.”

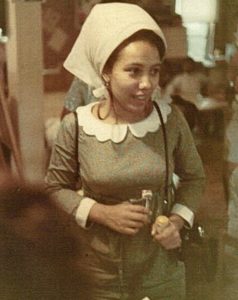

Derby, who would later earn a doctorate in social anthropology and do pathbreaking work as a photographer, had already lived on a Navajo reservation in 1959 and had spent the summer of 1960 in Nigeria. As an educator, she was deeply interested in the work being planned in Mississippi, but initially refused Moses’s overtures due to other pressing commitments. It was when she saw footage in May 1963 of deliberate attacks by Bull Connor’s snarling German Shepherds and pressurized fire hoses aimed at the bodies of Black children marching in Birmingham, Ala., for voting rights, that she relented. “I said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it. This is horrible, I will do what I can to help,’” she recalled.

Agreeing to go to Mississippi for a year, she stayed for nine.

“I was already deep into African culture, the diaspora, and the importance of us knowing our heritage,” Dr. Derby says, “and I wanted to see all of this in Mississippi.”

Derby, who had met many of the inspiring literary figures of the Harlem Renaissance including Langston Hughes, and who was herself already a poet, painter, and Katherine Dunham-trained dancer, dreamed of a theatre that would be an umbrella for the arts. The arts, she felt, could help spark the imaginative leap to spur mass action just as Martin Luther King, Jr.’s oratory had at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

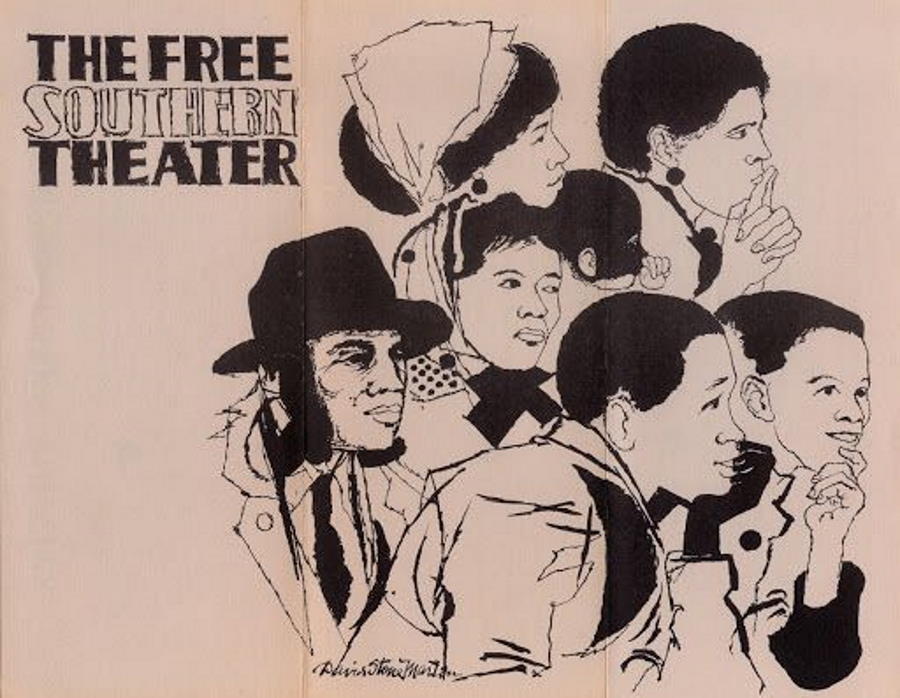

John O’Neal agreed with her. He would be one of her eventual partners in founding the Free Southern Theater, though he initially came to work in SNCC’s developmental literacy program, while Gilbert Moses, another FST co-founder, was an editor at the Mississippi Free Press, which published from 1961 to 1964. They were based at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Miss., which in 1963 was, Derby said, “a hotbed of Civil Rights activism.”

This trio made the case to their peers that “we needed to have a cultural arm to take the message to people about the importance of the Civil Rights Movement, about the new image for Blacks, and a new way of dealing with ‘the man’ and racism,” Derby recalled.

O’Neal and Moses became roommates and continued the conversation about what a theatre could accomplish for the movement, and Derby sometimes joined them at their apartment for these after-work discussions. As time went on, though, she feared that their idea of a touring repertory theatre was losing momentum. Growing tired of what felt like endless talk, she challenged the two men to transform their ideas into action, or, as O’Neal would put it when recounting FST’s origin story: “Doris said, ‘If we’re gonna do it, let’s do it!’”

They piggybacked off Tougaloo’s drama workshop, led by William Hutchinson, and, working with the students, put on some plays with Civil Rights themes in the 1963-64 academic year. Charged up by the enthusiastic response and transformative potential, the trio went to New York to fundraise and obtain pertinent scripts. Derby had some letters from Langston Hughes that opened the door to John Oliver Killens at the Harlem Writers Guild Workshop (where she was a member), and they became friendly with David Baldwin, brother of author James Baldwin.

“We got some people to say that they would be interested in supporting us, Harry Belafonte was in at some point, and we went back to Mississippi, where we began putting things into motion for the upcoming summer,” Derby recalls.

A Scary Business

They were lucky to have a pool of willing actors and ready places to perform, including in Freedom Schools, in churches, and on the front porches or land belonging to independent Black farm families who owned their own homes. But their main challenge was getting the people they most wanted to reach to show up.

“Let’s say we had a play occurring at a farmhouse, and we’re trying to get people coming from all around the area,” Derby explained. “They had to decide: Am I curious enough? Have I been exposed to the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and what people are talking about in Civil Rights? Is my life, work, or family going to be in danger if I go?”

Derby called it “a scary business,” because the very act of being an audience member then was courageous. If white bosses or landlords got word their employees or tenants were taking steps to pursue their Civil Rights, Black sharecroppers or laborers could lose their jobs, homes, and/or be thrown off the land. Most famously, it happened to fellow SNCC organizer Fannie Lou Hamer’s family, whose plantation owner also seized their car and the contents of their house. In fact, it was such a frequent occurrence that in 1965 Derby, with others, would work to establish handicraft cooperatives to generate income for those who lost their livelihoods this way, also building a network of Liberty House stores to sell the dolls, candles, leather goods, and other artifacts the cooperative produced.

“Anything that was Civil Rights-related was considered by the white supremacists to be a challenge, and anything anyone did in Civil Rights, anything positive for Black people, you were possibly subject to violence and intimidation,” Derby said. They lived in the state that W.E.B. Du Bois called “double consciousness,” always keeping in mind that how they saw themselves was not how others saw them. “If we were stopped by the police, we’d say, ‘Yes, ma’am,’ ‘Yes, sir,’ to get out of that situation,” she recalled.

Surrounded by the omnipresent threat of potential violence, Derby came to see nonviolence as a crucial movement tactic, but not necessarily a way of life. “I was very happy to be in the presence of independent Black farmers who had guns to protect us,” she said. “I’m not against that. And in the car, if you have a gun on the floor in case some rednecks stop you, you do what you have to do.”

When people did turn up for FST’s productions, it was often the first time they were seeing a play apart from Gospel pageants at church. Many were blissfully unaware of such theatrical conventions as the fourth wall.

“Sometimes people thought they could go up and say something and become involved,” Derby said, adding that was fine with the folks onstage, who were trying to find a happy medium between the mode and the mission. “We thought, maybe we can establish a new, evolved type of theatrical experience, one that is born out of this need for a Civil Rights breakthrough,” Derby said.

Their approach was self-consciously “bottom up,” with a narrative emphasis on Black working people as theatrical subjects. Their aim was to counter an almost total media blackout—which included in those days radio, newspapers, television, and movies—on “anything positive about Black people, heritage, or politics. We were responding to the situation we were in. We had to do it for ourselves. It came from us, our spirit, our struggle, our experiences.”

They produced original scripts by Moses and O’Neal, some of which were based on ideas from audiences and movement folks, as well as scripts from more well known playwrights. They looked for works that spoke to the universal human condition, but also to the particulars of the circumstance of Black people in Mississippi, which was one of overwhelming racial prejudice and discrimination. They focused on easily understandable and straightforward works, like Purlie Victorious by Ossie Davis, or an adaptation of Alex Haley’s Roots.

One Doris remembers as particularly interesting was Day of Absence by Douglas Turner Ward. Its conceit was to imagine Black workers suddenly subtracted from a town’s functioning in order to show the inconveniences and harms, mild to extreme, of living without the benefit of Black labor and ingenuity.

“Let’s say Blacks invented the street lights,” Derby explained. “We’d have somebody walking down the street who has an accident because there’s no street light.”

Theatregoing as Organizing

As a supplement to the plays, O’Neal imported a democracy-building feature from SNCC’s political meetings, inviting audience members to sit with the theatre artists in a circle after the shows and collectively hash out their understandings.

“John brought that to the plays, because a lot of times people didn’t understand all this theatre business, and they wanted to be involved,” Derby said. “So sitting around after, we’d talk about what’d happened; people would tell stories, relating their experience to the play. John would tell people in the audience, ‘You’re the actors, let’s hear your story.’”

Their efforts were at times surveilled and their people arbitrarily menaced. Sometimes white people or personnel from local sheriff’s offices would attend their shows and just sit there. Derby recalled that on other occasions actors and set people were harassed or were the subjects of bogus arrests. “It was not something that was without imminent danger,” Derby recalled, “depending on where you were, when you did it and whose place you were performing at.”

Because men and women shared the risks of this work equally, it wasn’t hard to puncture the more outmoded gender expectations some people showed up with. Both Moses and O’Neal confessed that at first they thought Derby would be there to do what they wanted—i.e., make coffee and take notes. Derby said she cured them of that attitude pretty quickly. “I’d say, ‘No, I’m not taking notes, or I don’t want to take notes, or maybe I’ll take notes—it just depends.’” Decision-making was more egalitarian than it sometimes seemed, regardless of who was out front.

“In the movement overall, Black women were doing all the things that needed to be done and making those decisions, and telling the men, ‘This is what’s going to be done,’ even if they were saying, ‘This is what I want done.’ We ignored the guys when and we would go ahead and do what we needed to do.”

She remembers the women as being very clear about their mutual dependence with the men but also their demand for mutual respect.

“In the movement, if we’re going to be on one end of the line and able to save your life, then you have to listen to us,” Derby recalled the argument going. “But we expect you to save our lives too. Okay, maybe you’re stronger than us, but if we have to be strong, if we have to have guns, we’ll do that also.”

Similarly, she didn’t have any problem in working with white people “if they would do what we needed them to do.” But, she added by way of emphasis, “I always had my Black focus and determination on what it was we needed to do to bring about equality and bring about the recognition of our equality.”

Another legacy of her stint in Mississippi: a series of beautiful photographs she took of folks she worked with and for there, creating a unique record of that time and place.

Beyond Mississippi

Derby worked with FST until it moved to Tulane University in New Orleans in the latter part of 1965, explaining, “I felt that the core and everything that we were developing needed to be in Mississippi.” Moses and O’Neal believed the theatre had a better chance of surviving by joining forces with director/teacher Richard Schechner at Tulane because of the institutional resources, networks, supports, and protection he could offer. Derby said she sees this difference of opinion in personal terms.

“I am an educator as well as a creative person in many areas, and I wasn’t tied to having a career in the theatre,” Derby said. “If they had stayed in Mississippi, I would have done more with them. It probably would have evolved into a more permanent role with FST in fundraising and public relations.”

In 2015, she was reunited with Junebug Productions in New Orleans, FST’s successor theatre, where she serves on the board. Earlier this year, she, with help from Junebug executive artistic director Stephanie McKee Anderson (she/her), created the Dr. Doris Derby Creative Spark Award, a $5,000 prize that will be given annually to one Black woman artist or collective to support their artistic practice. This year’s recipient was the New Orleans-based company No Dream Deferred.

The award lifts up the necessity and wisdom of materially supporting Black women artistic leaders so that, unfettered by material hardship, they can unleash their creative genius on a world that is hungry for it.

“It’s what this moment is calling for,” Junebug’s Anderson told me. Establishing the award institutionally is a way to give Dr. Derby, who is 81 and coping with a cancer diagnosis, “her flowers” while she is still present. It also concretizes Junebug’s almost spiritual commitment to her: that even after she joins the ancestors, the name Doris Derby will be spoken often by her successors in leadership roles whose example she has inspired as well as the beneficiaries of her strategic generosity, in perpetuity.

“Everything that I am is because of Black women,” Anderson said, “starting with my mother and my grandmother and all of the women who have become big sisters and surrogate moms in my arts space. I am so honored and humbled to be able to call Dr. Derby one of my moms.”

Derby’s motivation in funding the award is grounded in Black America’s political history and political possibility, the precise terrain in which she has creatively trucked since her earliest days of political consciousness. She helped establish the monetary prize to ensure “a legacy of remembrance of what happened in the past, tying it to the future. America is in trouble, so Black America is too. The enemy always takes steps to change things around and keep us from making headway. We have to be aware of that, that it can possibly go backwards. We can never think otherwise.”

Frances Madeson (she/her) is a writer based in central Louisiana who focuses on liberation struggles and the arts that inspire them. A contributor to American Theatre, her recent theatre writing also appears in Scalawag, Bayou Brief,and The Progressive.