Optimism has always flourished among committed theatre artists, but many eventually face the heartbreaking realization that sometimes it is best to step away from theatre and leave it behind.

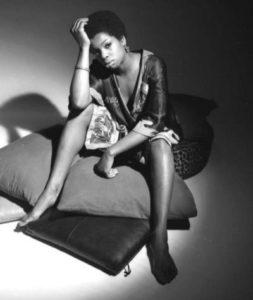

This is a lesson Krishna Kaur knows well. Kaur began studying with Yogi Bhajan in 1970, and has been teaching the art and science of Kundalini yoga and self-awareness for over 40 years. She opened her first yoga center in South Central Los Angeles in 1972, and is now well respected in the field. But before she took the name Krishna Kaur (meaning “Princess”), she was known as Thelma Oliver, and worked as an acclaimed dancer, actress, and singer who earned critical praise in the 1960s. Here is dancer, actress, and singer Thelma Oliver in her own words, talking about her life before and after the transition.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: What was Thelma Oliver’s childhood like growing up in a family of five in California?

KRISHNA KAUR: I was born in Los Angeles. My mother was born in Los Angeles. My father was born in Austin, Texas. He died when I was 6 years old, leaving my mother with four small children. My mother remarried a few years later and had my little sister. We were a happy family of five children, three girls and two boys. We didn’t have a lot of resources available to us, but I never felt we were poor. I remember really enjoying my childhood.

You studied dance with Jeni Le Gon, who was quite the actress and dancer; it’s been stated that she was the first Black woman to establish a solo career in tap dance. What was your experience like studying with her? Did you know of her reputation at the time?

I met her when I was 14 years old through her niece, who we called “Little Jeni.” She knew my sister in junior high school and suggested that we start taking dance lessons with her aunt. I learned much later about Jeni Le Gon’s history as having been a dancer and singing in the movies. She wanted so much to make sure that we little Black kids had a chance to actually experience professional dance teachers. She brought in other teachers to expand our technique. She brought in a ballet master, Lazar Galpern; he was a very strict and beautiful man. I really loved him a lot. She wanted us to have discipline; she wanted us to have the foundation and the techniques that all dancers would need, Black or white, to succeed in their craft. She brought in Archie Savage, a famous Afro-Cuban dancer and choreographer. He danced with the famous Katherine Dunham and her company.

Since we were neighborhood kids, and she lived in the neighborhood, we became a part of her dance troupe automatically. If you knew how to dance, knew the positions, remembered the rules, you became part of the Jeni Le Gon Dance Company.

You are from an artistic family; your mother did some singing, and your father, Cappy Oliver, was a trumpeter who played with Lionel Hampton and other established musicians. What do you think you gained from your family that helped prepare you for your artistic career?

I think I had the seed of art inside of me because both of my parents were artists. There is a way of looking at life when you are a Black artist, especially in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s. There was a way of seeing life, and enjoying life, and honoring life, and appreciating all the small things in life, and having a scope of welcoming all people in all situations no matter who they were. I didn’t know my father very long because he died when I was very young, but my mother talked about him a lot. That made me feel like I knew him just from the stories she shared, and all the beautiful things his friends would say about him. He was a very spiritual man, very patient, and very giving, and very serving. My mother had the same kind of nature; she was very patient and very giving.

In 1959, when you were only 20, you were a big hit in Jeni Le Gon’s Caribbean Fiesta at the International Folk Festival in the Philharmonic Auditorium at the Wilshire Ebell Theatre in Los Angeles. What was this experience like, and what did you gain from it that prepared you for your future?

I was a hard worker and a passionate little soul. Being with Jeni Le Gon at that Wilshire Ebell Theatre…made me feel like I was going someplace and that I could succeed in fulfilling my dream. To be in that theatre felt like I was a kid who longed to fly a plane finally having the opportunity to do so. This was one of the biggest moments we had been in since I started dancing with Jeni three or four years prior as a little 14-year-old. It felt like a natural thing for me to do; it gave me a sense of freedom, a sense of confidence, and clarity around my vision of myself. It was a very fulfilling time in my life.

In 1961, you decided to drop out of school and traveled east with Oscar Brown Jr.’s interracial musical Kicks & Co. The musical was not a success. But Lorraine Hansberry took over as director, replacing Vinnette Carroll. What can you share about Vinnette Carroll?

She was so powerful, an amazing theatre person. She loved it and put her heart into it.

What was your experience like with the musical?

I was in my first musical here in L.A. in 1960. The play was called Fly Blackbird, about the Civil Rights Movement, and I had a leading role in it; it was my first acting role, along with being a dancer and a singer. The producer and choreographer from Kicks & Co. came to L.A. auditioning artists for a show that was bound for Broadway. I was selected and brought to New York to audition again for the producers. They ended up choosing three of us to return and be a part of the production. They chose Nichelle Nichols, me, and Al Freeman Jr. Nichelle Nichols got one of the leading roles and I was brought in as her understudy.

Were you there when Lorraine Hansberry took it over or did that come after?

I was there from the beginning and I was there to the very end. I was there for the audition before the rehearsals started. I was flown from L.A. to New York for rehearsals, and I was there when Lorraine Hansberry took over the directorship around the time we were set for the tryout performances in Chicago prior to an opening in New York. Chicago was the place where the show actually folded. We didn’t finish our run in Chicago. We went back to New York not knowing what the future would hold.

In 1963, The Blacks reached its 700th performance Off-Broadway, making it the longest-running serious drama in Off-Broadway history up to that time. Many actors were in and out of that cast over its long run: Vinie Burrows, Harold Scott, Moses Gunn, Esther Rolle, Louise Stubbs, Louis Gossett Jr., Cicely Tyson, Godfrey Cambridge, James Earl Jones, Raymond St. Jacques, Maya Angelou, Roscoe Lee Browne, Charles Gordone, and others. Micki Grant told me she was just happy that she was in it. What was your experience like in that show, and were you in the original cast?

I was not in the original cast of The Blacks. It started before I got to New York. I was invited to replace Cicely Tyson by the producer in December 1961—I’m guessing around these dates. The producer, Sidney Bernstein, had seen me in Kicks & Co.’s desperate attempt to attract additional backers in New York in hopes of reviving the show after it failed in Chicago. Mr. Bernstein called me in to audition for the role. It was a new style of theatre for me, a classical avant-garde style. I learned a lot, loved it, and got better every week, as I was called in several different times to play the role as actors came and went. It was a great opportunity to hone my acting skills. And I had a good time playing alongside Lou Gossett, Esther Rolle, Vinie Burrows, and others. Every Black actor who was progressing in the business at some time was in The Blacks. For me, a newcomer in New York, it was a great opportunity.

You appeared on Broadway in Sweet Charity in 1966—your first show on Broadway, playing Gwen Verdon’s sidekick. Bob Fosse conceived, directed, and choreographed the musical. What was unique about that experience, and what was it like working with Fosse?

What was unique for me was I was on Broadway. I had been Off-Broadway with The Blacks and things that I loved, and that was great. But every actor, singer, dancer, or performer dreams of having an opportunity to be on the big stage in New York, Broadway, doing what you love most and what you have trained years for. It’s like your big break to be finally recognized and appreciated. The orchestra is big, the audience is big, and the director and choreographers are big, the producer is big. To me it was a dream of an opportunity; it was a chance, and it was fun

And I loved Gwen Verdon. When I saw her in the movie Damn Yankees, before I even got to New York, I fell in love with her. I said, That’s what I want to be, a triple threat: I want to do the singing and dancing and acting. Having a chance to work with her was just absolutely a dream. She was a genuine artist, and we were good together. Bob Fosse had a very interesting style in his choreography. He had his own cute style of doing things. [Laughter]

You played the role of Helene in Sweet Charity on Broadway and Paula Kelly played it in the movie version. Were you considered for the movie?

Yes, I was. In fact, Bob Fosse tried to have me play my role in the film. But whatever the negotiation was on that level, he came back and apologized that he couldn’t get me in. I didn’t even know he had been trying. But I deeply appreciated that he tried.

You not only danced with Donald McKayle, you also studied dance with him at the Herbert Berghof Studio. What can you share about that experience?

Donald McKayle was amazing; he was a powerful teacher and choreographer. In fact, he utilized dancers with different skill sets and kinds of training that fit the texture of what he wanted. He created a ballet called District Storyville; it was one of his pieces that he brought me into for a very specific role that he choreographed around my style and strength as a dancer. He was a dream to work with.

You worked with many of the legendary Black actors of the 1960s and 1970s. One I would be remiss not to ask you about—people don’t talk too much about him anymore—is Roscoe Lee Browne.

Roscoe Lee Browne was a classic! Strong and commanding voice that reaches the rafters of any theatre. Very powerful presence and an incredible human being. He was an amazing actor for whom I have a lot of respect and appreciation. He was in The Blacks when I was in it.

You appeared with Rod Steiger in the award-winning film The Pawnbroker as a prostitute. This was 1964, and there was a controversial nude scene in which you bared your breasts. In retrospect, what would you like to share about that experience?

I played a prostitute in The Blacks; I played a prostitute in Sweet Charity; I played a prostitute in House of Flowers. Those were the roles I seemed to attract, and I found them to be the most interesting characters to play. So being a prostitute was not a big deal for me at all in The Pawnbroker. The issue I learned later that I did not understand before we shot that specific scene was what Sidney Lumet meant when he asked me during my interview if I would mind baring my breasts. I was surprised at first, but then I recalled that they never show bare breasts in movies. I figured he probably wanted to shoot over my back with no bra straps showing; I could be okay with that. Imagine my shock when I realized that it was going to be a full-frontal shot! I was embarrassed and very upset with myself that I had agreed to a fantasy I created in my own head—I had fantasized that what had never been done before would not be done this time, and just because there had never been a major film that showed full-frontal nude breasts, that there would never be such a shot. I had given my word and so there was nothing to do but to get over it. Fortunately, it was handled very gracefully in the film. So I feel fine about it now.

You went to Scandinavia in Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth with E. G. Marshall. What can you share about that adventure?

Deciding to join The Skin of Our Teeth was not an easy decision, but it was a pivotal one. My friend Esther Rolle was in that production as well. I love the classics. They stretch you as an artist to go deeper and find the subtleties in you personally that connect you not just to the character you are playing, but to yourself. I had to find my character Sabina in me. I was already searching for me at that time, so it was perfect timing to get out of New York for a bit. We started rehearsing in Stockholm for a few weeks and opened the play there before moving on to Oslo and other places. I enjoyed the challenge of it. E. G. Marshall was really quite a giving person and a compassionate artist in a mixed cast of Blacks and whites.

You were supposed to travel for four months in the late 1960s, but you ended up traveling for two years. You traveled to Russia, Holland, Spain, Germany, France, Algeria, Senegal, Morocco, and Ghana, among other places. What was the most memorable experience you had while traveling?

When I was in Europe, I was trying to understand more about myself, not just as an artist, but as a Black woman on the planet. The Civil Rights Movement was very strong during the 1960s. Many were searching for answers, clinging to hope, determined to be a part of the change we wanted to see in the world. It was a time of personal searching for me and getting out of New York was a good move for me at that time in my life. While we were in rehearsals in Sweden, Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated. I was shocked, angry, stunned, you name it. I went through so many emotions, as we all did, including E. G. Marshall.

After The Skin of Our Teeth closed, I stayed on that side of the Atlantic Ocean thinking I should try to make my way down to Africa. There were several countries obtaining their liberation from the Europeans at that time. That sort of got me motivated to set my feet onto the African continent and continue looking for my way to worship God. I spent some time in Senegal, Guinea, Ghana, and Nigeria. I found it cleansing, invigorating, informative, comfortable, and a very cozy time learning about my people from my people. Definitely important time well spent.

You were having quite the artistic career in movies and theatre when you made a big career decision. You left your artistic career behind and changed your name from Thelma Oliver to Krishna Kaur. What is the narrative of this major life change?

Well, I think for a long time when I was in New York, and when I was doing plays, certainly when I was in Sweet Charity, and everything after that, I was asking myself the questions which were in a song Charity sang in the show: Where am I going?” How will I know? How was I supposed to worship God? I was always a very religious person. I had certain beliefs deep within me: Number one, that God is everywhere, and it doesn’t matter how you worship Him. I was also looking for a way that I could more directly serve my people, my community. When I came back to California after my journey around the world, I found that I could help my people best with the technology of yoga. I opened up a yoga studio in South Central Los Angeles, and within a matter of a year after I returned—it wasn’t my plan, it just sort of happened—I was able to help people get out of stress, put their health together, and more effectively respond to situations they can’t control.

Life is hard for our people. You can be dead in an instant—even if you are just jaywalking across the street. I just wanted to help as much as possible. I wanted to give them skills that they could choose to use or not. What you use is yours. If it doesn’t work for you, just let it go. People were ready. I was there.

There is poetry and drama in the artistic life onstage. How do you find poetry and drama in the work you do now?

Shakespeare says, “All the world’s a stage,” and I try to remember that everywhere I go. Seeing life as poetry helps me see the purpose in it all, including the challenges that we go through. If we can see them as gifts, and grow from them, then I believe the world has a chance to elevate.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion are important considerations now in our society. Can you talk about how those were in play when you were working as an actress, singer, and dancer in the 1960s?

[Laughs] Is this a test?

No. But if you were acting, dancing, or singing now, how would you compare that to the 1960s?

I would say that it is the same then and now because I am the same now as then. I have the same heart, the same spirit to enjoy life, and the same thirst to be a part of the change I want to see in the world. When I teach yoga and see the light go on in a person’s eyes, I feel I have done my part to help them see life from a more elevated perspective. Yes, I’m the same now as a yoga teacher in Los Angeles as I was when I was in the theatre in New York. In fact, one day I asked my friend Esther Rolle, when I had been teaching yoga for many years after being back in L.A., I said, “Esther, you knew me in the theatre in New York and you have never said anything about what I am doing now, and whether you are surprised or not.” And she responded, “Child, you have always been like that.” And she was right. We both knew it.

In retrospect, what are some of the factors that made you successful in theatre and movies early in your career?

I am not sure that I can answer that, because I never looked at myself from the outside before. I might say because I am genuine, hard-working, a lover of the arts, willing to do whatever was needed, and willing to go beyond the beyond. I was really there for the whole show. It wasn’t ever just about me. I wasn’t afraid; I didn’t have any fear. I could take disappointment very well, and I am a good support person.

What did you learn from theatre and movies that prepared you for the role that you ultimately transitioned to?

To just be me.

Nathaniel G. Nesmith (he/him) holds an MFA in playwriting and a Ph.D. in theatre from Columbia University.