On June 4, 2020, Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Theatre joined a growing chorus of performing arts organizations offering support to the uprisings that followed the police killing of George Floyd. “As America’s Oldest Theatre, we have witnessed our country’s challenges for over 200 years,” read a graphic posted to the company’s Facebook page, referencing its claim as the longest continuously operating theatre in the English-speaking world. “This is our country’s chance to take its own story in a new direction, where we all share equal rights and work together to build a better future. We encourage you to listen to the voices asking their country to recognize that Black Lives Matter.”

Yet some in the local community feel that the Walnut, as the largest and most visible theatre in the region, has not done enough to listen to the concerns about diversity, equity, inclusion, and access within its own walls—not only in the past year but throughout its history as a predominantly white institution in a diverse city. Those worries were exacerbated when, after a year of inactivity, the company’s dormant Facebook page returned to life with the announcement of a full, in-person 2021-22 season, beginning in September with Beehive: The ’60s Musical. In contrast to the lofty rhetoric of the summer before, this message looked like a return to business as usual.

“We were waiting over the past year for them to say anything,” said Jenna Pinchbeck (she/her), an actor who appeared in the Walnut’s 2019 production of Legally Blonde: The Musical. “They posted a Black Lives Matter statement and it’s been silence since then. They were silent for a year, almost exactly.”

In 2020, Pinchbeck and several other members of the Philadelphia theatre community had planned to send a letter to the company’s executive leadership and board of trustees, asking for transparency and accountability in the wake of the industry-wide We See You, White American Theater statement, which enumerated demands for U.S. theatres to meaningfully diversify their operations. “It was kind of a call-in, instead of a call-out, just to ask what they were doing,” Pinchbeck recalled. But the group scrapped the plan after some voiced concern that the letter’s tone was too deferential to the Walnut.

Instead, many turned to social media—in particular, by replying to the season announcement on Facebook—to ask broader questions and make sharper claims about problems at the theatre. The lack of action following the Black Lives Matter uprising was one issue, but several others emerged, including concerns about artist safety and inequitable wage structures. The floodgates had opened, and comments on the post ballooned to over 200 in a matter of days. (The majority have since been deleted or hidden.)

Pinchbeck’s own message was particularly pointed: “How will you make your space safer for BIPOC, trans, and disabled artists? How are you going to make women feel safe with Bernard around?” she wrote, referring to Bernard Havard, the company’s president and producing artistic director. “What have you done to hold him accountable?”

Within days, Pinchbeck received a cease-and-desist letter.

Pinchbeck first became aware of Walnut Street Theatre when she moved to Philadelphia from New York in 2015. Over the years, she worked for the company in several capacities, including as a teaching artist and performer in their children’s theatre series. She earned her Actors’ Equity membership during the run of Legally Blonde.

She described the experience of performing on the company’s mainstage as “a huge and wonderful thing.” At the same time, she acknowledged ongoing conversations within the community about problematic professional practices. “There were whispers of poor treatment,” she said. “I was warned when I got my contract that I needed to not speak up if I witnessed something that doesn’t seem right if I wanted to keep my job.”

Others who have worked at the Walnut felt similarly—that it was not a place where dissenting views were welcomed. “As part of an artistic team, there was a certain amount of responsibility, and a certain amount of respect that came with that responsibility,” said Ryk Lewis (he/him), a sound designer who worked on 15 productions at the theatre between 2006 and 2008. “At the same time, there was always a definite feeling that your opinion only went so far.”

Still, since the Walnut had, with their supportive statement last summer, taken the step of recognizing systemic racism in a public forum—a move that prompted its own share of derisive comments at the time—it seemed like an opportunity had finally arisen to speak frankly about aspects of the company culture that should be changed. “It felt like there was a small opening, almost an invitation, to have a conversation,” said Liam Mulshine (he/him), an actor who also worked in the Walnut’s ticketing services department from 2015 to 2020. “It seemed like they were implying that we, the theatre, need to be held accountable.”

That this didn’t come to pass led Pinchbeck, among others, to take a more public stand. The cease-and-desist letter to her felt to many in the local acting world as a definitive end to the conversation, at least on the Walnut’s part. Although the letter—which Pinchbeck shared on her public Instagram profile—made reference to her comments about diversity, it was the suggestion that Havard had acted in an untoward way around women that triggered the theatre’s response.

A Walnut Street Theatre representative declined to make Havard available for an interview but requested a list of written questions, which were answered by email. “Ms. Pinchbeck falsely accused me of engaging in acts harming the safety of women,” Havard wrote in response to a question regarding the cease-and-desist. “We believe this is defamatory.”

Pinchbeck maintains that her comments were not an allegation of criminal behavior, but rather referred to Havard’s alleged practice of entering dressing rooms backstage, sometimes without awaiting a formal invitation—something she claimed is common knowledge among actors who’ve worked at the Walnut. Although she said this did not happen to her while she was working at the theatre, the practice has been corroborated to her by other women. “Even before I started the contract, the threat that this could happen at any time made me feel uncomfortable,” she said.

According to Havard, the Walnut’s board of trustees launched an independent investigation upon learning of Pinchbeck’s comments and found the claims against him meritless. But Alex Keiper (she/her), an actor who appeared in the company’s productions of The Humans and Proof, told me she experienced it firsthand.

Keiper, a Barrymore Award winner and veteran of the Philadelphia theatre scene, said she often felt apprehensive about auditioning for Walnut productions, having heard from friends that Havard and other casting associates sometimes made comments about performers’ bodies. “Generally, going in to audition for them always feels a little funky—you always feel a little more nervous, and it feels more judgmental than other places,” she said. “I’d heard all these stories about people having the experience of Bernard saying, ‘She’s too fat for this,’ or, ‘We can’t have someone who looks like that onstage for two hours.’”

When Keiper was cast as Brigid Blake in The Humans, which Havard directed, friends who’d worked with the company encouraged her to do her hair and makeup before rehearsal. “It’s important to Bernard that you make an attempt to look good, and he won’t want to talk to you if you don’t look attractive, basically,” she said. She was also told to remain in costume after coming offstage on opening night, because Havard would be making the rounds backstage.

“If you changed, he was going to come right when you were changing, knock on your door, and ask you to open up,” she recalled. “Sure enough, two minutes after I got in my dressing room—a knock on the door, and he opened it right away, and I rushed over and felt like I had to be gracious.”

Keiper believes this practice has more to do with power than harassment, and that it was not necessarily tied to gender per se. “It didn’t feel sexual to me,” she said. “It felt like he gets to do what he wants to do, and no one can say otherwise. There would be no way to do anything about it.”

For her part, Pinchbeck has stood by her statement, going so far as to retain her own attorney and issuing a counter letter to the theatre. Viewing the initial cease-and-desist as a silencing tactic, she felt that it reflected the company’s practice of minimizing or dismissing criticism. She saw it as an opportunity to amplify what people have been saying privately about their experiences working at the Walnut for years. Rather than fade quietly into the background, she began organizing a protest.

Opened in 1808, Walnut Street Theatre regularly describes itself as America’s oldest theatre, although it has existed as a non-for-profit producer only since 1983. Since then, the Walnut Street Theatre Company has been led continuously by Havard, an English-born impresario who came to Philadelphia from Atlanta’s Alliance Theatre. Under his watch, the company has cultivated 56,000 subscribers, which it claims is the largest subscription audience in the world, and its total assets for the 2019-20 fiscal year were upwards of $25 million.

Opened in 1808, Walnut Street Theatre regularly describes itself as America’s oldest theatre, although it has existed as a non-for-profit producer only since 1983. Since then, the Walnut Street Theatre Company has been led continuously by Havard, an English-born impresario who came to Philadelphia from Atlanta’s Alliance Theatre. Under his watch, the company has cultivated 56,000 subscribers, which it claims is the largest subscription audience in the world, and its total assets for the 2019-20 fiscal year were upwards of $25 million.

Within the city’s artistic community, however, the theatre has often been seen as insular, both in its programming and its staffing. “The Walnut is unwilling to work with people they haven’t worked with before,” said James Jackson (he/they), a production designer and technical director who has worked in Philadelphia since 2001. “I couldn’t get my résumé to the right person to even be considered for a job. Without bringing in people who come from other communities, how do you give access to people of color?”

Ryk Lewis, who is Black, said he never personally experienced overt discrimination while working at the Walnut. But, he added, “It was evident that among the performers and other artistic teams that being involved with the artistic team as a Black person was very unusual.”

Rob Tucker (he/him), a veteran actor and music director, said he heard stories about the theatre’s exclusionary practices going back to his student days at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts. “All of my Black actor friends had just stopped trying to get through that door,” said Tucker, who briefly worked in the Walnut’s education department but never performed in a mainstage production. “The messaging was that you could understudy here and there, and get paid $25, but don’t expect to be in the shows. But they also don’t do our shows.”

Even when the company does produce a show that centers a Black or Latinx perspective, the experience can be fraught, some report. When Donnie Hammond (she/her) was cast as Daniela in a 2013 mainstage production of In the Heights, it seemed like a career breakthrough. “It was extremely exciting at first, because Walnut Street felt untouchable,” she recalled. “I had already auditioned for them a bunch, but it never felt like a place where I would be hired. To do that show was a big deal.”

The initial rehearsal process was exhilarating, but Hammond quickly noticed a divide. “I realized there was nobody on the other side of the table that looked like us,” she said. This partly reflected the larger reality of working in predominantly white institutions, where creative teams frequently skew older, white, and male. It became problematic, however, when issues of cultural competency arose, and cast members were left to fill in gaps of knowledge.

Hammond noted that Michelle Gaudette, the production’s choreographer, had scant experience with the specific styles of movement and music employed in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s score. “How do you have a show that’s so heavily influenced by hip-hop and the flavor of Latin dances, and the person at the helm has no idea of any of that?” Hammond wondered. “As much as I liked her as a person, we were going into dance rehearsals knowing that the dance captain was doing so much of the work—and he had to, because she had no idea.”

Throughout the process, Hammond never saw the production team take account of the areas in which they fell short. “There was nothing that was presented to us saying, this is what we’re doing to try and make us better at doing our jobs,” she said. “Even that would have felt like, they know they shouldn’t be in these positions in the first place, but they’re trying to make up for it. It definitely did not feel that way.”

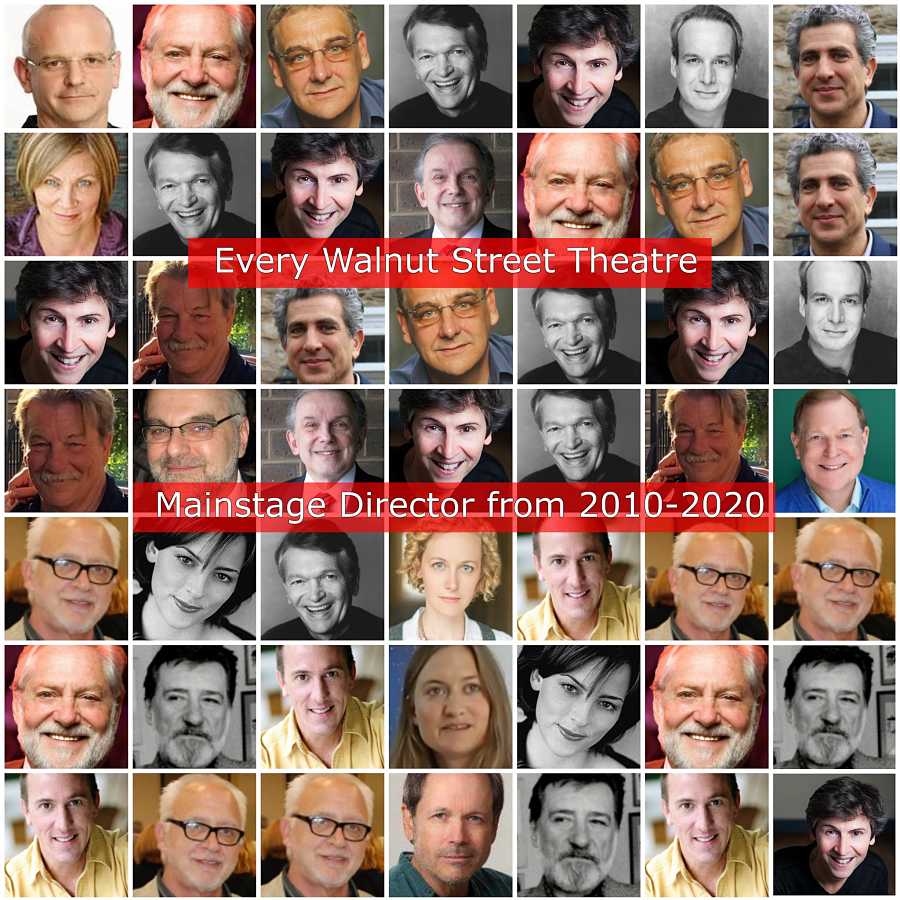

Others have also taken notice of the homogeneity of the Walnut’s directorial pool. A widely shared graphic on social media created by Mulshine aggregated photos of every mainstage director between 2010 and 2020. All were white, and of 49 productions, only four were directed by women. A similar graphic of the company’s current board of trustees showed 10 white men, four white women and one Black woman.

“I found those visuals to be perfectly revealing, and I think a lot of other people found them shocking as well,” Mulshine said. “And all that information was totally public, so it’s not some secret. If they are going to say something on their social media but have very different practices in reality, they should be held accountable.”

In his email response, Havard pushed back on the claim that these data reflect exclusionary hiring practices.

“There are many individuals who are involved in our productions—these statistics represent a small fraction of our team,” he wrote. “Prior to March 2020 when we closed due to the pandemic, 32 percent of our permanent theatre employees were persons of color, and over the past three seasons, 27 percent of our performers onstage were persons of color. For the 2021-22 season, one of the five directors [of a mainstage production] is a person of color.”

Another issue that’s moved to the forefront of the discussion is wage disparity, particularly during a pandemic that forced large swaths of the theatre industry onto the unemployment rolls. Even by the standards of executive leadership, Havard’s salary raises eyebrows; in the fiscal year 2018-19, he earned $745,015 in total compensation, according to publicly available tax filings. By contrast, other administrative positions within the company tend to start at minimum wage. When Mulshine was first hired in 2015, he earned $7.25 an hour, which was raised to $9 after three years of employment.

“I took the job for the opportunities that I hoped it would open up for me, but I was really surprised they were hiring people to work for so little,” he said. “It was something that my colleagues and I grumbled about to each other. I think there was an understanding with the managers of our departments that it was very low pay, and they were going to try and be flexible in other ways. They were understanding to a point that it wasn’t a sustainable job, but beyond that, I don’t think there was any communication about the possibility of better pay.”

Flexibility was not a job perk enjoyed by the Walnut’s corps of apprentice workers. The company’s Professional Apprentice Program extends to all aspects of the theatre, from acting to stage management to administrative duties. Designed to attract recent college graduates and early career professionals, the season-long residency pays a weekly stipend of $350. The rate, according to one former apprentice, has remained unchanged since 2001. (“Apprentices receive a tuition-free scholarship to participate in the program that includes a stipend to assist with expenses associated with participation,” Havard wrote in response to this claim.)

“When they tell you that you’re going to be paid a stipend, it sounds like you’re going to have room to take on other work to subsidize it,” said the apprentice, who requested anonymity for fear of professional retaliation. “That does not turn out to be possible. It’s basically a full-time job, and the stipend amount does not reflect that. And we’re still being paid the same rate people were making 20 years ago.”

The apprentice recalled a training session in which the current class was shown a breakdown of the theatre’s annual budget, including salary information. Although no one expected to be making as much as the boss, the wage gap between Havard and themselves was shocking. “They didn’t think we would take issue with that, or even bring it up. But we were the first ones to ask why they are paid that much and we are paid this much,” the apprentice recalled. Following the incident, according to the apprentice, those who spoke up were warned not to discuss salary discrepancies again and told they needed to be better behaved.

Kevin C. Vestal (he/him), a former public relations apprentice who attended the same training session, confirmed that apprentices initiated a conversation about wage disparities upon learning executive leadership salaries. He did not recall being personally reprimanded for doing so, but said it was possible others had been. “We have no knowledge of this claim,” Havard wrote in response to a question about the incident.

When the Walnut ceased live performances in March 2020, it laid off most of its staff, including all apprentices. Because apprentices were not categorized as employees, but rather as students of the company’s education department, many found it difficult to collect unemployment. “The only way I was able to make it through the pandemic with any sort of income was because of the [Pandemic Unemployment Assistance] laws,” said the former apprentice. “I’m from Pennsylvania and have lived here through the pandemic, but a lot of people in my apprentice class ended up having to go back to their home states and fight their states’ unemployment systems. It was a mess for a lot of people.”

Asked whether salary cuts were put into effect for staff who remained on the payroll during the pandemic, Havard wrote that “[a]ll staff, including myself, had a reduction in compensation.” True enough: Havard earned $566,569 in the fiscal year 2019-20.

In early June, a cadre of local theatre professionals formed Protect the Artist Philly, a grassroots organization focused on creating systemic change within the local theatre community. The group has called for Havard’s removal as president and producing artistic director of Walnut Street Theatre; for the implementation of an anti-racism action plan within the company; and for the creation of a permanent director of diversity, equity, inclusion, and access within the theatre’s executive leadership structure, among other demands. A petition started by the group has garnered 785 signatures to date.

Pinchbeck says the group’s initial protest, held on June 18 on the eponymous Walnut Street outside the theatre, drew about 100 demonstrators. There are plans to protest the opening night performance of Beehive: The ’60s Musical in September if their demands are ignored. She also emphasized that the function of the group extends beyond this specific issue. “There are a lot of different directions we can envision it going that are bigger than just holding the Walnut Street Theatre accountable,” she said. “We’re hoping to also start uplifting theatre companies that are taking care of their people and uplifting the art that needs to be happening right now, because there are a lot of people out there doing the work.”

Hammond said she’s encouraged by the potential for progress as the theatre industry returns to in-person performances. “For people who have lived this, we’ve always known, we always saw, and we were always screaming at the top of our lungs,” she said. “But because we were such a small portion, and it wasn’t affecting anybody else, people just went on with their lives. Once the world was forced to shut down, nobody could be too busy to not notice anymore. There are enough people who are good, and who are actual living allies, who are sitting and seeing all these things play out in front of them. They know that now is the time, and enough is enough.”

For Alex Keiper, the issues at the theatre haven’t been screamed about so much as whispered. “The reason it was whispered and not shouted about,” she said, “was because if you talked about it to upper management, they would make sure you felt the recourse. They would make sure you felt you had no right to speak—in fact, that you were wrong to do so. I hope that the whisper network is just given a little more encouragement to say things louder and not be so concerned with how management will treat them afterward.”

Asked what members of the local theatre community might expect from Walnut Street Theatre when it resumes public-facing operations in September, Havard wrote, “The events of the last year and a half have advanced important discussions within the Walnut and the entire theatrical community. We can all do better and look forward to the industry as a whole working to make a more inclusive community.”

Mulshine feels that in a perfect world, inclusivity should be among the core tenets of Walnut Street Theatre’s mission. In practice, though, he thinks they’ve fallen well short. “There’s a Latin phrase, vox populi, that is associated with the Walnut,” he said. “It means ‘voice of the people,’ and Bernard always repeats it, but I don’t think he’s talking about all of the people when he says it. I hope that he, and the theatre generally, will be open to the idea that when you limit yourself to doing only primarily white theatre for primarily white audiences, there is well over half the city you are excluding—as audience members, and as storytellers and artists.”

Cameron Kelsall (he/him) is a writer based in Philadelphia.