It has been a week of Broadway reopening announcements, as the nation’s commercial theatre machine lurches back into action, and everything from mainstays like Hamilton to more dubious prospects like Mrs. Doubtfire have posted new dates. As my infrequent visits to midtown Manhattan indicate, the city is pulsing unevenly back into some kind of public life, and something like normal theatregoing looks poised to resume as soon as the fall.

The financial district, however, is another story. On a recent weekday visit to Brookfield Place, the commercial mall in the former World Financial Center near Battery Park, as well as to locations near Wall Street, the city felt neither entirely empty nor particularly bustling. It felt instead like a sleepy weekend in a corporate downtown, a time when most of the everyday office workers aren’t around (though, come to think of it, I’d been to this part of town on weekends in pre-pandemic times, and even then it was busier than it was last Friday).

That’s part of why both Brookfield Place and the Downtown Alliance, the Business Improvement District for Manhattan’s financial district, are hosting site-specific theatrical events over the next few weeks, both of them produced or co-produced by En Garde Arts: A Dozen Dreams, an immersive guided sound installation in an unused storefront in Brookfield Place, and Downtown Live, a performing arts festival comprising 36 in-person outdoor performances, co-presented with the Tank and Downtown Alliance.

If the name En Garde Arts, or its artistic director, Anne Hamburger (she/her), ring a bell, it’s because that company was known throughout the 1990s for its site-specific work at various Manhattan locations: Reza Abdoh’s Father Was a Peculiar Man, staged outdoors in the Meatpacking District, or Chuck Mee’s Orestes, mounted on a twisted metal pier in Penn Yards, or JP Morgan Saves the Nation, a musical of sorts by Jeffrey M. Jones and Jonathan Larson, staged outside Federal Hall on Wall Street.

Now Hamburger and her company, which took a break through the 2000s while she worked for Disney and the La Jolla Playhouse, are staging what she somewhat reluctantly recognizes as a kind of comeback.

“I guess it’s a return to my roots,” Hamburger conceded last week after giving me a tour of an empty storefront in Brookfield Place that has been transformed by visual and experience designer Irina Kruzhilina, lighting designer Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew, and a tireless crew into a sort of walk-through cabinet of curiosities for A Dozen Dreams (which runs May 13-30). Hamburger would be quick to point out the work that En Garde Arts has done in its last decade that departed from the old site-specific model: Basetrack, a multimedia collaboration with combat veterans, or last year’s Fandango for Butterflies (and Coyotes), a touring music-theatre piece about immigration whose run was cut short by COVID lockdown.

Ever since then, something seems to have stirred in this mercurial impresario. “Rather than go online, like so many people did,” Hamburger said, she thought, “How can I return to my roots if the theatres are closed? I know how to use the city as a stage. I did it for 13 years.”

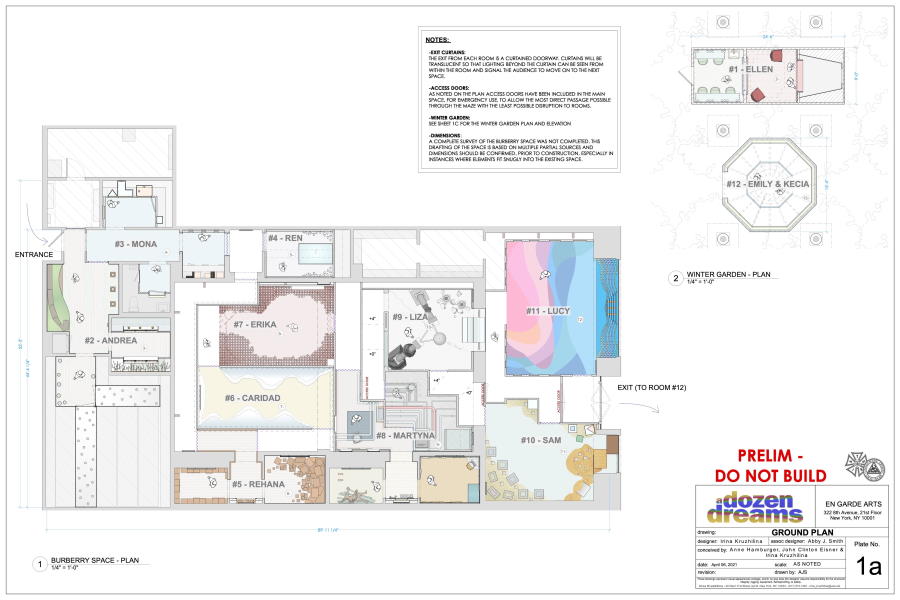

The idea of a walk-through installation of audio playlets about dreams began with her, but when she reached out to the Lark’s artistic director, John Clinton Eisner, for recommendations of playwrights she might commission, he quickly became an equal collaborator in the piece’s conception. So did Kruzhilina, whose extraordinary designs find visual analogues for the playwrights’ evocative musings on memory, motherhood, race, sex, disease, and dreams of both the waking and sleeping variety.

Once the trio figured out “three clusters”—the 12 pieces move roughly from memories to reflections on the present, then to visions of the future—it fell to Kruzhilina to shape the space into what she thinks of as “a labyrinth, so it’s not even individual dreams, but more like one person dreaming, and we’re just walking a path inside this giant brain.” The big challenge, she said: “How do we disorient the spectators so they don’t know exactly where they are, how much time has passed? If it’s just 12 rooms, a series of cubicles, it might become very repetitive.”

The list of writers is impressive, as is the range of their contributions, which run from ruminative to raucous and all points between: They include Ellen McLaughlin, Andrea Thome, Mona Mansour, Ren Dara Santiago, Rehana Mirza, Caridad Svich, Erika Dickerson-Despenza, Martyna Majok, Liza Jessie Peterson, Sam Chanse, Lucy Thurber, and Emily Mann. Crucially, we will be hearing their voices (and in a few cases, seeing their faces) as they deliver the work in recordings (embellished by sound designer Rena Anakwe). Like Blindness, one of the first in-person theatrical events on offer in New York City, A Dozen Dreams is a play without actors—or rather, a play in which headphone-wearing audience members, who will travel through the piece in groups of one or two, are the actors.

The list of writers is impressive, as is the range of their contributions, which run from ruminative to raucous and all points between: They include Ellen McLaughlin, Andrea Thome, Mona Mansour, Ren Dara Santiago, Rehana Mirza, Caridad Svich, Erika Dickerson-Despenza, Martyna Majok, Liza Jessie Peterson, Sam Chanse, Lucy Thurber, and Emily Mann. Crucially, we will be hearing their voices (and in a few cases, seeing their faces) as they deliver the work in recordings (embellished by sound designer Rena Anakwe). Like Blindness, one of the first in-person theatrical events on offer in New York City, A Dozen Dreams is a play without actors—or rather, a play in which headphone-wearing audience members, who will travel through the piece in groups of one or two, are the actors.

There will be performers in the Downtown Live festival, which runs for 36 performances over two weekends (May 15-16 and May 22-23) at three different outdoor spaces in the lower financial district, including the loading dock of a JP Morgan facility. It’s another illustrious list of artists: Eisa Davis, with Kaneza Schaal and Jackie Sibblies Drury, as part of their recently announced exploratory theatre collaboration Afrofemononomy; the Tank artistic director Meghan Finn with playwright-performer Kaaron Briscoe; playwright-performer David Greenspan; Brazilian Theater Company Group .BR; performance artists Baba Israel and Grace Galu; music and storytelling duo James & Jerome; classical singer-composer Katie Madison; Kuhoo Verma (Octet) with Justin Ramos; and theatremaker Ellen Winter with Machel Ross.

Finn (she/her) joined Hamburger and me last week near the makeshift performance venues to talk about the past year and what the opportunities of this moment.

When the pandemic lockdown began, Finn said her attitude was, “We have to keep going. Because we work with a lot of emerging artists, they’re super adept at making online content. Theatre didn’t invent the internet, and so we just made stuff.” Stuff indeed: The Tank has offered over 400 livestream performances since March 2020. And while the Tank’s midtown space is gearing up for an in-person return in the coming weeks, Finn couldn’t say no to joining En Garde Arts in presenting a live festival downtown.

“Because there are no tourists going to the Battery right now, and all these buildings have been emptied out, a lot of the stores are struggling,” Finn said, looking around the district. Hamburger chimed in: The leaders of the Downtown Alliance “have said repeatedly, ‘This is not philanthropy. We are doing this because it can contribute to the economic development of the neighborhood.’” Finn, who said the free-but-reservation-required festival performances “sold out immediately,” has offered package deals so that people can “come see something, go get something to eat, catch another one.”

Looking past this month, Finn admitted that one of her concerns is “the loss of artists from the city. A lot of them have left.” While this was a concern even pre-pandemic due to high rents, Finn said it’s different now. “I used to always say, the kids are all right—they keep coming and pushing through. Every night I would stay after work and see whatever crazy stuff was on our stage. The punk rock kept happening, you know? Now I’m worried about it. I think they will come back—I mean, they’re already starting to call me for space. But it’s not just about the Tank, it’s about the whole ecosystem.”

Indeed, this has been on my mind a lot, both as a theatre journalist and a New Yorker. When and how exactly will live performances, shared with a diverse crowd of strangers—always one of the main draws of living and working in this bonkers metropolis—come back? And what will it be like when it returns?

“I just felt like, I’m gonna fight for live, you know?” Hamburger told me. And the labyrinth of A Dozen Dreams, not to mention the moveable feast of Downtown Live, offer “a way back toward live theatre.” She said the playwright Lucy Thurber, when asked to contribute a dream monologue, responded, “Oh my God, you mean you’re asking me to do something that has an opening date?”

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre.