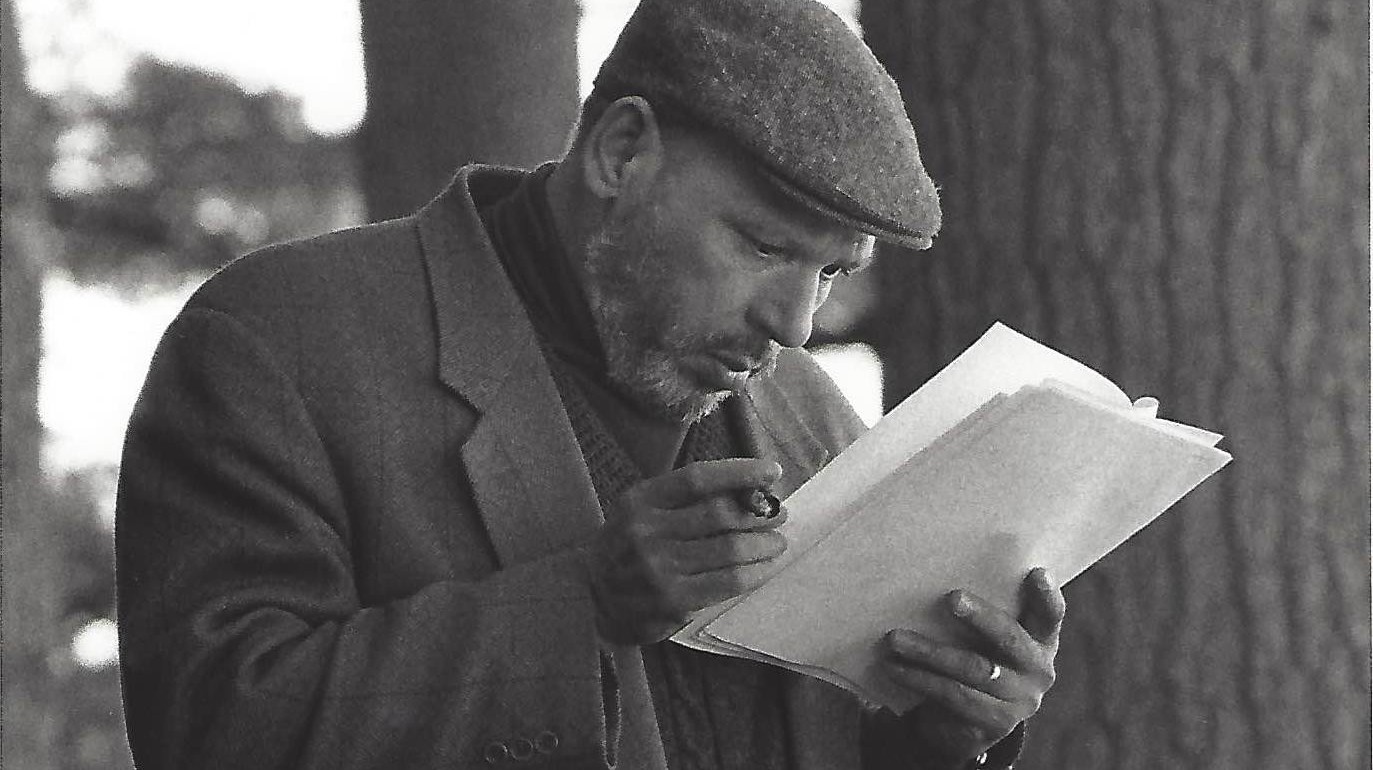

In April 1987, August Wilson won the Pulitzer Prize in Drama for Fences; he was only the third African American to win that award. I had the good fortune to have a conversation with him over lunch at the Hotel Edison restaurant in New York City a few months later, on July 12, 1987. Wilson was gracious and humorous, and went into character as he described his writing, hinting at plays that were forthcoming.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: What did it mean to you to win the Pulitzer Prize?

AUGUST WILSON: It is a great honor. I think it added a sense of legitimacy to my work and what I am doing. There is a character in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom who says, “As long as Black folks wait for white folks to put a crown on what they say….the longer they wait for white folks’ approval, the longer they have to wait to find out what they are about.” It added a sanction—a sanction that it needed, actually, in order, particularly, to get Blacks to come to the theatre.

You actually think that your winning the Pulitzer Prize will encourage more Blacks to come to the theatre?

It calls attention to the play. Then the play itself does the rest, because they come and see it and they go home and tell their friends.

As a writer, what do you see as some of the negatives and some of the positives of such recognition?

I don’t see any negatives; as a writer it doesn’t affect my writing. It doesn’t affect my work, what I’m doing and the way I write. It doesn’t put any pressure on me. In fact, it does the opposite; it adds fuel to the fire, so to speak.

You’ve mentioned that you started writing plays around 1973. You have excellent craftsmanship, from the two plays I have seen, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and Fences. How did you learn the craft?

Well, first of all, it was 1977—no, it was 1979, actually, when I started to write plays. I worked many years as a poet. For 22 years now I have been working as an artist. You develop a certain approach to a craft in terms of poems; poetry is a very highly crafted art form. Whatever craft I learned in the poetry; it is just a matter of transferring it. I think that Aristotle’s Poetics is just an intuitive sense. So if you are going to tell a story, you have to tell it well, and tell it in such a way to keep the audience interested. I just sit down and try to tell a story, keep the scene interesting, and with the same approach I used toward poetry. I am not ignorant of craft. I just never studied play craft, etc. But I think that if you are going to create art, it should be crafted. It should be as highly crafted as you can make it, and that is what I tried to do with my plays. I guess what I am saying is, it is an intuitive sense with me.

You have won the greatest prize in drama, as did Charles Gordone and Charles Fuller before you. Although your writing style is completely different from theirs, what is it that you think the three of you have in common that aided you in getting the Pulitzer?

Well, the obvious thing: I thought your name had to be Charles. [Laughter] I think it is as simple as that we all wrote good plays.

You think that quality and talent prevailed?

I think so.

The three of you are also dealing with a deeper understanding of racism. What would you like the audience to leave the theatre with, as far as an understanding about racism from your perspective?

I would like them to leave the theatre with the understanding that the Black characters they see in the play are African people. And that as African people, they have a different cultural response to the world than do white people. And that there is nothing wrong with that. In fact, that is the source of their strength. So, if white or Black audiences are seeing the play, if it dawns on them at some time during the play that these are African people, then they begin to see the commonalities of different cultures. And they understand, even though these are African people, they wrestle with the same questions that all of humanity wrestles with. Why God got to be so big? That is one of my questions in Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. There is nothing outside of Black life; the largest philosophical question that man can ask is contained in Black life. That is what I want the audience to leave the theatre with, with that understanding: that there is nothing outside of Black life that is different because the people are Africans.

You did an extremely good job in that; what I got from people is that they are not looking at these characters as Black characters but as human beings. But you also deal with the destructive element of racism, the inherent evil within racism itself.

In addition to the universalism, they also recognize that the people are Black and that the content of their lives here in America has been racism; it is something that Blacks in America had to deal with. Although there are no white characters in Fences, the white world is very much there, because the white world exerts a pressure on that family from the outside. Racism is a part of Black life in America. So if you are going to write about Blacks, you have to write about racism, because that is part of their lives.

One of my concerns is how racism actually affects Blacks. We don’t think of how it can actually force us to be destructive. Would you like to comment on that?

Well, I think I commented on that in Ma Rainey in a sense. At the end of the play, there is transference of aggression because of the pressures of racism. We have a tendency to turn it inward as opposed to pushing it outward.

“Writing is a process of self-discovery. If you are honest, you are forced to confront the part of yourself that you always have a tendency to run away from, which is the deepest part.”

You have mentioned that you have refused offers from Hollywood. Do you think that might be something you would want to do in the future? It seems like that with the talent you have, it would be something you could conquer. Do you think you would like to do a screenplay?

I would love to do screenplays of many of my plays, of Ma Rainey and Fences. If someone wanted to make a movie, I would love to do that. Yeah, I would like to write the screenplays 10 years from now if someone would still ask me. After I have accomplished and established myself as a playwright, and continue my work and development, yeah, I would like to. It is a fascinating medium. What concerns me are the utter lack of respect that Hollywood has for writers and the utter lack of control that you have over your work. Robert Townsend is one of the best screenwriters in America, and he still has no control over his work as the artist. That is the thing that has kept me away from the movies.

You just mentioned “after you establish yourself as a playwright.” What more can you do to establish yourself as a playwright?

I follow [director] Lloyd Richards’s lead. I still see myself developing as a playwright; every play I do I learn more and more about the craft, and more and more about the form. I certainly do not see it as the end of—I certainly want to write two or three more. I see this as a step in my development.

That’s very interesting. Most writers write a great deal about themselves. What have you, as a writer, learned about yourself—what type of wisdom have you gained from writing?

That is why you write. Writing is a process of self-discovery. If you are honest, you are forced to confront the part of yourself that you always have a tendency to run away from, which is the deepest part. I think it has made me a better person and a stronger person, having written these plays, because it has forced me to confront myself in this landscape of the self with your little bag of all the imperial truths that you have learned that is your weapon against the self.

When I interviewed Charles Fuller and Charles Gordone, they both said they had learned a great deal from you, from seeing your plays. I don’t know if you saw No Place to Be Somebody or A Soldier’s Play. Is there anything you think you gained from them?

Wow. They are like my predecessors. I am building on a foundation, right out of the Black tradition; I’m building on the foundations. All the Black influences, like Amiri Baraka and Phillip Hayes Dean, all those guys. I’m just continuing their—it’s very interesting that they say that.

Charles Fuller said, “What I learned from August, I think I learned how to be more poetic in my language as far as putting it onstage. That is something that August made me more aware of.”

Let me say this, and in one sense I’m embarrassed: I don’t know Charles Gordone’s work. I haven’t read it, I haven’t seen No Place to Be Somebody, and I haven’t read A Soldier’s Play, although I have copies of both. I haven’t been to the movies in eight years, so I didn’t see the movie of A Soldier’s Play, and I wasn’t in New York when the play was going on. In the same sense, though, I haven’t read A Raisin in the Sun. When I started writing plays, I very consciously did not read them. I haven’t read Death of a Salesman, I didn’t read Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, I hadn’t read Ibsen. The only Shakespeare I read was in school—we did Romeo and Juliet. So that’s all I know. I don’t read plays, very seldom do I go to the theatre. So, I don’t know their work. It sounds terrible, but I don’t.

As a playwright with a voice, a well-respected voice, what steps do you think Blacks should be taking to correct some of the inequities that we have in society now?

I think I would have to claim the African parts of ourselves that we do not see as valuable. I have a character in The Piano Lesson and he’s talking about this piano. The piano had been used to purchase members of the family during slavery and the grandfather has carved African masks like totems of the family, and the grandfather stole the piano and brought it into the house and people have died over the piano. In 1936, they are in Pittsburgh, and there’s a mother who has not told her 11-year-old daughter the story of the piano. Her brother is telling her, “You have to tell Maretha about that piano. The day Papa Boy Charles brought that piano into the house, they ought to mark that date down with a special meaning, say throw a big party, invite everybody, I’m talking about a big party. You got her thinking that there ain’t no part of the world that belongs just to her, but if she knew the story of the piano, then she could walk out here and know who she was, and she would know what her relationship to the society has been.”

There’s strength in that. I think one of the reasons I wrote Fences is that our parents have shielded that from us, trying to protect us from the indignities of things they had suffered being Black. My mother never told me that she went down to Woolworth’s 5-and-10 and they wouldn’t give you a bag because you were Black. That’s not the kind of thing that you want your kid to know, so you keep that away from your kid. She would accept that. I think the thing to do is to pass it on as opposed to holding it in there. I think once we begin to do that, and we understand that we can participate in a society as Africans—if we do that, then we are participating from our strength, from our strongest point. That is our difference, because Black people and white people do not think alike, and that is our basic philosophical difference, our different approaches to life. We are living in a white society, and that is a dominant thing, and we try to adjust ourselves to fit in, when I think that white America has to accept us on our terms—the fact that we do things differently. We don’t stand in line; Blacks go up to the popcorn counter, at a Black movie, and they crowd the counter and they shout, “Hey, give me two boxes of popcorn when you get done!” Then the white folks say, “Well, there’s a line back there,” and the man looks around and he has even seen the line, he don’t mind going to the line, but his initial impulse is not to get in the line. Whereas if one white person is standing there, then the next white person comes and stands in the line. It’s just different approaches. Rather than adapting ourselves to white America, I think we should demand that white America accept us on our terms as Africans, and we can participate in a society as Africans.

Exactly what is it that we should do to get white America to accept us on our terms?

We have to first accept ourselves on those terms.

You’ve been quoted as saying, “Speaking of Black people, within their history, in their transition from being Africans to becoming Americans, they have lost something central to their identity.” What is it that you think we have lost in the process?

The very thing, first of all, was acceptance of it. That white America has taught us that everything Black is valueless, that you are a worthless person, that you are not a worthwhile person. They used to arrest people in the South and put them in jail and would charge them with worthlessness. It boggles my mind. For the most part, we accept that and in order to become worthwhile, we begin to act like white folks. And we do things and adopt their mannerisms and styles, and some of us even decorate our houses like white folks. Black folks’ sense of style is different, Black people decorate and furnish their houses differently than white people do. You can’t change that; it’s just the way people are in the world. You see what I’m saying? We lost acceptance of ourselves.

A lot of black people like to call themselves Afro-Americans.

Sure. We’ve been here for 400 years and there’s nothing wrong with that. There’s such a thing as Italian American and Japanese American. The Japanese are a perfect example—they don’t participate, they go through this society as Japanese. White America allows them their cultural differences. They don’t allow us our cultural differences. A Japanese guy could come in here and he can bow and walk around the table three times and do all kinds of stuff, and a white person will say, “That’s odd, but he’s Japanese.” You know African Americans come in here and they talk loud, and we do—we talk loud. We’re not allowed.

For instance, I saw six Japanese guys in a restaurant eating breakfast. They all sat in a line and ate their breakfast and they chatted among themselves and they got up and they left. I sat there and I watched them and I thought, now what would have been the difference if six Black guys came in here. The first thing I noticed is there is a jukebox and none of the Japanese guys played the jukebox. Now a Black guy, the first thing he’d do is walk over and put a quarter in the jukebox, and the other guys would’ve said, “Hey, Rodney, play A6.” And he would’ve said, “Hey, man, get out of here, man, put your own money in and play your own record, man, don’t play my record.” The second thing I noticed was that nobody said anything to the waitress. Now if you get six Black guys in here, they gonna say, “Mama, wow, she look good, but don’t talk to her, you don’t know her.” So now the other guy gets up to play another record, and a guy steals a piece of bacon off his plate. And then he says, “Who’s messing with my food, I ain’t playing with y’all.” A white person might say, they don’t know how to act, they talk loud, they don’t like one another, guy won’t let him play a record, stole a piece of bacon from his plate, the bill came, nobody had money—guy said, “Gimme two dollars, man.” What is happening here is Black folks just being the way they are. They love each other, that’s the way they have breakfast together. And it’s different than the way white folks would do it, it’s different than the way Japanese would do it. What I’m saying is that they allow all the other ethnic groups to participate in the society with their cultural differences, but with Black Americans, the whites expect you to act like them.

I concur that there is a difference, but it also seems that there is a misunderstanding—whites misunderstanding Blacks, and Blacks misunderstanding whites. Whites seem to do things that Blacks consider to be inappropriate, and vice versa. It seems like it has been so long that we don’t understand each other.

There is one very big real difference, and that is that Black America knows white America, and white America doesn’t know anything about Black America. We have had to learn white America in order to survive. They don’t know anything about Black America. They walk by and they don’t see you, they do it in a very glancing manner. They never really see you unless they are forced to see us, which is one of the things with Ma Rainey I found out. It was like tearing open a curtain, and whites looking through a window at something they weren’t supposed to look at. They had never stopped to look. They see them four guys sitting in there, they would never look at them, they would never be concerned about anything, never think they were talking about anything, don’t matter, they’re just four niggers. Once you stop and look at them, then you discover that their world—their problems, the stuff they deal with—is the same as yours.

Knowing the legacy of this system, do you think racism is something that will be corrected? Do you think it will get any better, or do you think it’s a cycle?

I think it’s systemic; it’s a cycle. There are things that are perpetuated. Ever since man has been on the planet—we’re the only animal on the planet that has not learned to live with one another. You know the lions, and the whales in the seas, basically they have learned how to live with one another. But we have constantly been fighting and killing one another, starting with Cain and Abel. If you read the Bible, you got the Philistines, these people fighting those people, and it’s all about religious or racial differences. So it’s always going to be. It’s been. You know today in the modern world, we have this country here, we have mostly Europeans and then we have some Africans who the whites had brought over here some years ago, and we label it racism. But I don’t know if 20,000 years ago the same thing didn’t exist among some other people.

As a Black American, and also as a Black playwright, do you think that you will have the same opportunities as whites who have also won the Pulitzer?

I think so. Sure. I’ve been offered movies. I am getting my work produced. So I would have to say yeah. Without knowing what opportunities they have, I’d have to say yes.

One thing that I’ve noticed is that there’s a genuine quality of humanity throughout your plays. You don’t see that type of humanity in a lot of plays on Broadway. I get the feeling that you are expressing that life can be better, that our humanity can be better than what we have been.

I think so, yeah. And I think this is part of our responsibility, tagging on a line—each generation refreshes hope for the next generation. So that what they give you is fresh hope, and I think that’s what we have to give the next one. Otherwise, without hope, what’s the point?

That’s exactly what I mean, there is hope; it’s not a pessimistic point of view. There is something great about life.

I think so, yeah.

What advice would you have for younger Blacks who are trying to break into writing or become a playwright?

I would say, and this is the only answer that you can give, is to write. I heard this 20 years ago and it didn’t mean anything to me. You know everybody says that. I mean, the thing to do is to write and you must do it; the more you write, the better you become. I think I’ve been married to this for 22 years; I don’t do anything for 22 years and not get a little bit good at it. So one is to write, and to recognize again the chair that you’re sitting in is no different than anybody’s. And once you understand that, you’re capable of doing anything. You have to realize and believe this: You are capable of doing anything, ’cause you’re sitting in that same chair as everybody else: Ibsen, Shakespeare, Shaw, anybody. You have just as much right to sit there as they do.

And the third thing is, start anywhere. You don’t have to have the whole thing in your head when you start and have to know how it’s going to work out. And if you do, then it’s probably not going to be any good anyway, because writing is a process of discovery. I’ve talked to so many playwrights who are sitting and waiting to write a play because they don’t know how to start it. They don’t know what it’s all about; they haven’t plotted it out yet, so they spend months plotting. Just start anywhere. And then you’ll discover and find it.

It’s also interesting to me that you didn’t go to school to study playwriting.

I’ve sat outside Pat’s cigar store and listened to these old guys talking, and they don’t have no degrees in storytelling, but they can tell the most wonderful stories in the world. And it’s just people talking. If you listen to their stories, they have structured their stories in such a way—see, in African storytelling, a mark of a good personality is, how long can you keep the story going? So they’ll start a story and come up with all kinds of little sidetracks. One thing I noticed that they do is that they like to start talking about something, and then they’ll start talking about something else, and it appears to be unrelated until you get to the end.

This is the story of the difference between a colored man and a white man. All right now, this is from The Piano Lesson. Now you take some berries, and you eat you some of them berries. And they get good to you. And you say, “Oh, I’m gonna go out and get me a whole pot of these berries and bake me up a cobbler or bake me up a pie or something,” so you go out and get you some berries. See now, you ain’t stopped to look and see that they sitting on the other side of this white fellow’s yard. So you go on and get you a little pot of them berries, and now the white fellow comes along and says, “Well, that’s my land, therefore everything that grows on it belongs to me.” Tells the Sheriff, “I want you to go on and arrest this nigger and put him in jail, otherwise next time you know, these niggers have everything that belongs to us.” Now, see, he includes the sheriff in with him. But the sheriff, he don’t own no berries; after he haul you off to jail, this white fellow gonna give him some. So, he says, “Oh, I know where I can get some berries from Mr. So-and-So, he like me cause I keep the niggers out of the berry patch.” See, that only lasts so long. So, one day, Mr. So-and-So says, “I don’t remember you. See, you got to buy your berries.” So, in order to keep himself fresh in this fella’s mind, he got to catch another nigger in that berry patch.

Time go along and time go along, and he comes to you and he sells you the land. He says, “John, it’s all yours, but I’m gonna keep them berries. And come berry-picking time, I’m gonna send my boys over to pick ’em. The land is all yours, but them berries I’m going to keep them.” And then he goes and fix it with the law that them is his berries. See now, the colored man can’t fix nothing with the law, and that’s the difference between a white man and a colored man. I noticed they would announce what the story is about and then talk about something else. I’m sitting there as a kid and I’m saying, well, what does berries have to do with the difference between a colored man and a white man? They keep the story going, but they always arrive at the end and then you see the whole point of the story.

You see, with Ma Rainey…now I’ll never forget this. I walk in there one day and these guys are 60 years old, they are standing around playing the numbers, chewing tobacco, smoking cigars. One guy said, “Yeah, I come to Pittsburgh in 1939, come up on the B&O railroad.” And some guy said, “No, you ain’t come on the B&O, it don’t stop in Pittsburgh.” And then he proceeded to tell him all the places the railroad stopped. Then he said, “How you gonna tell me which railroad I come in on? ’Cause I know what the train was.” And this went on for like a week! Everybody come in here and it was a joke—like, tell this fool which way the B&O come. They knew or they didn’t know, and then some guy said, “Man, y’all still arguing about that?” And so I had something like that in Ma Rainey.

You have a wonderful sense of these stories. It is easy enough to say it is from an oral tradition, passed on from Africa. But you are not going to find too many Black historians telling these stories; sometimes people just can’t put it together, there’s something more than just the oral tradition. I don’t have a talent for putting together a story like that. Was this something in your family—did you come up around people telling stories like that?

When I was 20, since I grew up without a father, I had to go out in the community and learn what it meant to be a man. And I learned this from the social scene. The first couple of years were rough years. I was 22 and didn’t know how I was gonna make it to 23, and I looked up and saw these guys and they were 62, they were 65, and they had made it. So I thought, okay, let me go hang around them, and maybe I’ll learn how to get to 23 and 24 and how you guys did it. Please tell me, cause this shit is hard out here! How did you make all them years? I stood around listening to them and that’s the kind of stuff they talked about. They used to call me Youngblood, and they would ask me questions. One time they asked, “Hey, Youngblood, tell this fool ain’t the moon a million miles away?” They would argue about how far the moon was. “Ain’t it a million miles away?” So, I said, “Well, I think it’s 250,000.” And they said, “That boy don’t know nothing! But he has all them books and he’s carrying them papers…” Whenever they would include me, I felt honored. I stood around there enough times, I became one of the fellows.

I never thought about what proved to be valuable: the mannerisms of being, the way they were in the world. I was trying to write stories making all these characters talk like Europeans, trying to put poetry in their mouth; they eventually balked at it because it wasn’t them. I didn’t see in their speech, the way they talked, the value in it as literature. It was only in ’78 that I began to hear and listen and recognize the value of it, saying, this is beautiful, man, because they had that convoluted, structured way of telling it. What I discovered was that if you look at it, you could see their thought process. I discovered that Black folks have a lot of conversation run by implication. They will say something that will imply something, and the other person will pick it up and make it the wrong implication and then straighten you right up. “No, I ain’t talking ’bout that. I ain’t said that. I’m talking about what the man did when he came in the room. I ain’t talking about what he did when he left.” And then the other guy will say, “But you said to say what the man do, you didn’t say before or after.” And he says, “Well, I’m talking about what he did after he left.” Soon the conversation gets a little shifted out, and there’s never really a direct response to the question.

There comes a point where there’s some revelation, where a writer realizes: This is it, this is something valuable. Do you think that that’s the moment that really changed things for you?

Without question. That was the moment. Knowing it was valuable, and that it had largely for the most part been neglected. Everybody was passing over it. I looked inside and it was so rich and so whole, and it was like, wow, there’s all this stuff and it was all mine. It didn’t belong to nobody else; this was me. I had been looking for what was me. You know, having these records for 5 cents apiece from St. Vincent de Paul: Patti Page, Anita O’Day, Hoagy Carmichael, tunes by Cole Porter—I listened to all the records. One day I discovered a Bessie Smith record in my little pile and put that on and that was me. See, all the other records were somebody else, but this was me. And once I realized that I had something that belonged to me, I wanted to find out about it and claim it as mine. I never thought about the value, say, of my grandmother’s life, or these guys, all poor guys who struggled all through their life. You know they’re living on welfare, they got the little pension, the little retirement. It’s so beautiful and so full of so much wisdom and whatever, but nobody was paying any attention to them for the most part.

Thank you for the conversation.

Thank you.

Nathaniel G. Nesmith (he/him) holds an MFA in playwriting and a Ph.D. in theatre from Columbia University.