Rest assured: Before too long there will be countless theatre reopening stories to tell. This magazine will tell many of them, and I will undoubtedly write some of them.

This is not one of those stories. This is something different: In part it’s an attempt to talk myself down from the ledge as I gaze into the abyss that is the live performing arts field in this long COVID winter—a task in which I’ve enlisted the help of a number of sane, clear-eyed, relatively hopeful industry voices. And in part it is a plea for more realistic thinking on the part of theatre leaders, theatremakers, theatre fans, and politicians who genuinely want to help theatre and its workers survive, and see its audiences return safely.

The good news is that theatre will be back in some form. It has survived countless plagues, it’s an ancient art, you know the litany. But what form exactly? The cautionary if not quite bad news is that it will definitely not come back all at once in all U.S. cities and venues, and Broadway—the default industry standard and theatre “brand” in all too many peoples’ minds, not least New Yorkers’—is likely to be the last to reopen. We need not only to prepare for this uncomfortable fact, but to consider what it might mean for the performing arts to reorient their priorities. Could the center of gravity in the American theatre shift from Broadway and New York City, and might that not ultimately be a healthy development?

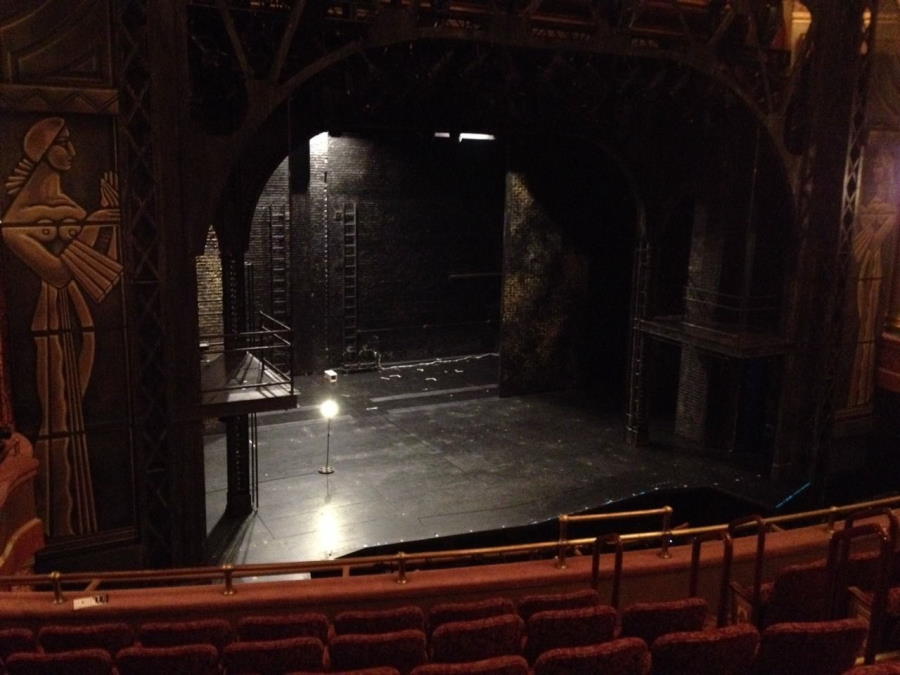

“There isn’t a one-size-fits-all answer,” Mara Isaacs (she/her) told me when I asked her when and how Broadway shows might return. Isaacs, a producer on the Tony-winning Hadestown, also worked for years as producing director at McCarter Theatre Center and now runs an independent performing arts company called Octopus Theatricals, so she knows all sides and sizes of the business. Broadway, as she would be the first to admit, is uniquely vulnerable to an airborne pandemic: A 41-house district in dense, mass-transit-served New York City, it relies on packing anywhere from 600 to 2,000 folks, bused in from all over the U.S. and the world, into cramped seats in century-old buildings with poor ventilation, eight performances a week, for roughly two-hour shows, many of them packed with actors singing their lungs out, and crews and orchestras sharing tight quarters. How many COVID alarms does that set off?

Obviously a critical mass of vaccinations will need to be in folks’ arms before any of that begins to be a possibility, which is why most Broadway leaders I spoke to are eyeing October for a “staggered reopening,” and even that with a degree of wariness. (I spoke to them before this week’s vow from the Biden Administration to get vaccines into everyone who wants them by the end of July.)

“I am an optimist—I want to say we’re going to figure it all out,” said Isaacs. “But even what we did before was barely sustainable. The community is going to have to be all in, and at least for the first six months or longer, until we know if people are willing to come into crowded spaces, all these shows will have to have a reserve, a cushion.”

In the meantime, there are spaces poised to reopen in New York City sooner than next fall and before comprehensive vaccination, including not only outdoor venues but many with flexible seating and less punishing business models—i.e., nonprofits. Susan Feldman (she/her), artistic director of Brooklyn’s St. Ann’s Warehouse, has been on a task force convened by Gov. Cuomo to strategize for reopening since last summer, on which she and her colleagues from the Armory, the Shed, National Black Theatre, and Harlem Stage have all been making a similar point.

“Our conversation has been about, can there be a pathway to reopening where everybody doesn’t have to stay shut until Broadway can reopen?” said Feldman. “Can we get the governor to recognize there can be an incremental reopening?”

The governor’s office, in conjunction with producers Jane Rosenthal and Scott Rudin, recently announced a series of “pop-up” performing events that will appear around NYC in the coming months, and the city of New York will soon offer applications for its Open Culture street permits, which will allow artists and companies to perform in public and charge for tickets starting in March.

“It’s not about getting box-office income,” said Feldman, who plans to have St. Ann’s participate in the Open Culture program with offerings in the park near the venue, with the option to move toward small events indoors by the summer should safety guidelines allow. “It’s about delivering arts to people; it becomes a different conversation, and not so transactional. It’s a whole other way of thinking about the work, which nonprofits already have going. We just have to get more funding.”

Corinne Woods (she/her), director of programs at Alliance of Resident Theatres/New York (ART/NY), said that her organization would be involved in the efforts of many Off-Broadway companies to participate in Open Culture. But she added, building on Feldman’s point, “One of the things that has been most challenging in this pandemic is that Broadway has been set up as what theatre is, so that Broadway standards, and Broadway’s ability to come back, have been set as the requirement for theatre to come back. That does not reflect the theatre field’s variety, especially when you’re able to step away from a model that’s so reliant on ticketing revenue. Which doesn’t mean that Broadway is bad or isn’t doing enough! Our survival is really linked together, despite having very different business models.”

That link is important. But so are the differences.

Cock-Eyed Optimism

“Producers by definition are hopeful, we’re optimists—who else would actually raise money for a Broadway show?” said Sue Wagner (she/her) of Wagner Johnson Productions, which has The Lehman Trilogy in the queue for Broadway and a new cabaret venue, the Midnight Theatre, in the works, both ostensibly to open in the fall. The flip side of that can-do optimism, Wagner’s partner, John Johnson (he/him), told me, is a certain restless fractiousness.

“Even though it’s one big industry, what was shut down last March were really 30-40 small businesses, each of whom has a different cash-flow situation, a different insurance situation,” he said. “The biggest frustration now is that producers are very good at being patient and waiting; they want to know, This is when we’re opening and closing, and, Can we make an event out of this. We’re all hopeful that most of the street will be open in the fall, but we’re not sure that’s going to happen.”

Even when state gives the green light to reopen, it’s not like Broadway can be switched on overnight. Most shows will need rehearsals to get back into shape, Johnson and Wagner noted, and marketing and advance ticketing will have to crank up again as well. The ensuing competition for resources and attention, Johnson said, could make the annual spring Tony Awards qualification frenzy look quaint. “It’s going to be this odd Cannonball Run scenario, where the gunshot goes off and people are just going to be scrambling,” he said.

As film and TV productions are increasingly ponying up for the extra cost of COVID-safe production, the question for Broadway producers isn’t so much the making of the work but the in-person sharing of it. As Wagner pointed out, “There’s a way to get in a room and rehearse right now, to keep people behind the proscenium arch safe. What we don’t have control over is 1,100 people walking into a building.”

Sammi Cannold (she/her) is more than sanguine about the prospect of full-capacity Broadway houses returning; she’s positively bullish about it. A director whose work over the past year has taken her to South Korea and London to stage musicals for Andrew Lloyd Webber’s company, she admitted, like everyone I spoke to, that social distancing is a non-starter for Broadway. But she said she’s seen firsthand how other safety measures have worked in Korea, and she thinks with some buy-in and effort the could “scale up” in the U.S.: improved ventilation, temperature checks, masking, sanitization, and strict crowd-flow management.

“What Korea’s example shows—and London has jumped on this, as well as theatres in Australia, Japan, and Argentina—is that if you put the protocol into these buildings and follow it, there’s a way to make theatre at full capacity safe some time before coronavirus is eradicated from the earth,” said Cannold, who noted that outbreaks have been traced to various public activities in Korea, but not to theatres. “Reworking Broadway houses to have different architecture so that everyone is six feet apart is not possible, but updating their filtration systems is.” Korean theatre venues are ahead on this score, in part because most of their buildings are 20 years old and younger; indeed, she said, their filtration systems tend to make the air quality inside theatres better than that outside them.

And, as Cannold reasoned, theatregoing under these conditions would rank lower on her risk assessment list than dining, mass transit, even going to the grocery store. “Even if you have people coming to theatre with COVID, theatres are uniquely controllable environments where they can be contact-traced, even after they leave the venue—that’s what’s happened in Korea. If we follow the protocol, it’s safer to go to the theatre than to go to a restaurant or ride on a subway.” It’s a message she feels needs to be urgently communicated: “If we don’t talk about this as a community, we’re not going to get anyone to come back.”

Getting audiences comfortable with returning to live gatherings is also one of the goals of the Shed’s founding chief executive and artistic director, Alex Poots (he/him). Located in the relatively new Westside development Hudson Yards, the Shed boasts two flexible spaces with state-of-the-art filtration systems (“I had no idea our HVAC system was going to become such a useful thing when we built it,” Poots marveled); one space even has the ability to fly out walls to become partly open-air.

Poots, who also sat on the governor’s task force, said the venue is actively seeking partners to produce events for which it will waive rental fees within a limited recovery window; among the groups he’s talked to are the Dramatists Guild, American Ballet Theatre, and Waterwell. He even told me, “If someone from Broadway wanted to do something at the Shed, we’d love to talk to them. We want to be helpful. We’re not commercial, so we can absorb those costs. I think it’s our duty to help our city. There need to be some live performances that are safe, that can build the case that a wider range of performances can come back. I think it’s important psychologically for New Yorkers that things start to reopen in the spring.”

Or, as St. Ann’s Feldman put it to me, “If places like ours are getting people used to going out in public, that would be good for Broadway too.”

A Buyer’s Market

Beyond serving as test cases for live performance, though, might there be a central role for New York’s nonprofit theatre sector in the story of the city’s arts revival? There is, after all, a powerful civic dimension to the arts’ return. As Jeffrey Omura (he/him), an actor and activist who is running for a seat on the New York City Council, and who plans to stress arts recovery if he wins election (the primary is in June), put it to me, “We pay so much money to live in these tiny apartments, and one of the things that makes it worth it is access to arts and culture. This is also true of corporations; when everyone’s working from home, why spend money on commercial real estate in NYC? The city has a strong case that the reason to be there is to be close to culture.”

While the centrality of Broadway as a cultural and economic engine can’t be ignored, there is also no ignoring that it in recent decades it increasingly came to serve tourists more than New Yorkers, and its high ticket prices have effectively constrained access to huge swathes of the local population. Not only is that likely to change when Broadway stages do reopen—as producer Brian Moreland (he/him) told me, “I think there will be a bit of buyer’s market in terms of tickets, and I’m fascinated to see what New York audiences will pay to see”—it is also imaginable that this year’s gradual return, what Poots called “a range of performances that are going to be able to stagger to the finish line in the fall,” will whet local audiences’ appetite for a wider range of fare, both at their neighborhood venues and on the Main Stem.

John Johnson told me he thinks that many big shows that had been circling Broadway for some time, waiting for a stage, may see some slots open this fall but are likely to wait until 2022 to see how things shake out. That could leave room for smaller, riskier limited runs, both of straight plays and musicals. Indeed, in the relative absence of tourists for some time, New Yorkers are likely to have more say over what’s on local stages, and more access to them, than at any time in recent memory, and the results could be refreshingly unpredictable.

This likewise opens even more potential for Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway companies, some of which have flexible seating but all of which have smaller spaces and the ability, in theory at least, to adjust the balance of earned to contributed income to accommodate lower-capacity audiences, an option unavailable to their commercial counterparts. At Playwrights Horizons, located just off Times Square, artistic director Adam Greenfield (he/him) pondered the notion that, if theatres like his were indeed to open before Broadway venues, it might go a long way toward overcoming the popular misconception that Off-Broadway is the “minor leagues, that we would like to be on Broadway but we’re not.”

He did express worry about “a rush to open, to be the first, which I think would be not good for the city. My hope is that we could have some kind of codified safety measures, more or less in tandem with each other, so audiences can feel that all Off-Broadway productions are working safely. If one theatre gets it wrong, we’re all going to suffer.” But in the sense that theatres like his have a mission “to serve, to provide richness and thought, nourishment to where we live, we are a public service. If we are doing our job, there is a distinct need for us, especially at times like this. So it seems logical to think that nonprofits will be in a position to lead the way.”

There’s another way that nonprofits have a responsibility to lead, and it’s not about seating capacity or safety protocols. Instead it’s about righting the wrongs of a field steeped in exclusionary, white supremacist aesthetics and economics. Super-charged by last summer’s Black Lives Matter resurgence, and fueled by the time for reexamination afforded by the pandemic lockdown, the demands for equity laid out by the We See You, White American Theater movement, among others, have added new dimensions to the already fraught choices theatremakers and institutions are making during this downtime.

The two obvious human responses to a crisis, it seems to me, are to run for safety, to the tried and true, on the one hand; and to stop and reevaluate everything you’re doing because you’ve got nothing to lose, on the other. I see both impulses at work among the theatre folks I talk to and follow, some of whom seem eager simply to get back to doing exactly what they did before, others who are earnestly embracing challenges to the many ways that American theatre business as “usual” was broken. But there’s no question in my mind which route the nation’s tax-exempt, public-oriented nonprofit theatres should take, and the leadership role they are called to.

“There are so many things that we’re trying to solve at once,” Mara Isaacs told me. “The very real problem of what this pandemic has done to our economic model and to people’s feelings of physical safety in our spaces, and also to address generations of discrimination and harm, and who gets to make the decisions—trying to address all those things is not about putting them in tension but about making a strategy. You can’t set one aside to address the other; they have to be addressed in a thoughtful, cohesive fashion. You can’t disregard the finances and think only about racial justice, and you can’t disregard racial justice and think only about finances.”

The reckoning goes deeper than that false binary, she said.

“This is something I’ve talked about for a long time, not even just through a racial justice lens, but through a survival-of-the-future-of-theatre lens,” Isaac said. “Nonprofits need to respond to societal shifts in the way we engage with entertainment, where it’s more product- than relationship-driven; my experience had been that the aesthetic was getting narrower and narrower, and what people want is more ways to engage. So we don’t just need more Black plays; we also need more different formats, new ways of engaging. This idea of the primacy of the single artistic vision is what we’re rallying against. It’s about creating access for artists and audiences. If after COVID this all goes back to one or two voices deciding everything, whether it’s critics or artistic directors or a board, it will just be a reinforcement of the way things used to be, instead of an embrace of risk.”

And while she doesn’t want to dismiss the financial hardship many nonprofits face, she did note, “Many have become more and more reliant on ticket revenue. Hopefully what the pandemic has done has shown them that may not be the model they should use.”

Talking to theatremakers for this piece has both sobered and inspired me, and I would place Miranda Gohh (she/her) firmly in the latter category. An aspiring young producer who caught the theatre bug as recently as Hamilton (“I saw myself onstage for the first time; it was life-changing,” she told me), she was only two-and-a-half shows into a job as company manager at Manhattan Theatre Club when the pandemic hit. Though she’s been furloughed since last April, she has not been idle: She helped organize the Industry Standard Group, a group of eight BIPOC producers whose aim, she said, is “to create greater access and participation in producing” for folks who’ve typically been excluded from the “insider’s club” that comprises most Broadway producers by lowering the financial threshold for their involvement. She also created an organization called Theatre Producers of Color to offer a 10-week, tuition-free course in producing, along the lines of the prestigious but very much not free Commercial Theatre Institute.

This forward-looking work has been both enlightening and empowering, she said. “It certainly has given me a lot of hope. It’s a tough field to make it in, even in normal times. But being inspired to share these stories with the wider world is what drives me to continue this work. I am fighting to keep my inspiration.”

Producer Brian Moreland (Sea Wall/A Life, Thoughts of a Colored Man) has kept his spirits up by looking forward—and outside. “The pandemic has shown us we need to think beyond our 41 buildings,” he said, referring not only to his still-extant plans to produce Charles Randolph-Wright’s play Blue at Harlem’s Apollo Theatre as soon as he’s able, but to the growing potential for the video capture and wide distribution of Broadway performances. I repeated to him my anxious shpiel about how, sure the theatre will be back, but in what kind of shape? And he replied firmly, “It’s going to be a good shape. I don’t know if we’re going to be able to have an opening night party. But there will be something on that stage, and there will be people in those seats.”

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre. rwkendt@tcg.org